Prose & Poetry - Literary Ambulance Drivers

A

remarkable number of well known authors were ambulance drivers during World

War I. Among them were Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, E.E.

Cummings, and Somerset Maugham. Robert Service, the writer of

Yukon

poetry including The Shooting of Dan McGrew, and Charles Nordhoff,

co-author of Mutiny On the Bounty, drove ambulances in the Great War.

A

remarkable number of well known authors were ambulance drivers during World

War I. Among them were Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, E.E.

Cummings, and Somerset Maugham. Robert Service, the writer of

Yukon

poetry including The Shooting of Dan McGrew, and Charles Nordhoff,

co-author of Mutiny On the Bounty, drove ambulances in the Great War.

At least 23 well known literary figures drove ambulances in the First World War.

If the list were expanded to include those working in medically related fields during the war, such names as Gertrude Stein, Marjory Stoneman Douglas, and E.M. Forster could be added.

The concentration of famous writers as ambulance drivers is unique to the First World War. W.H. Auden drove an ambulance in the Spanish Civil War and Walt Whitman sat with the wounded of the American Civil War. Novelist Vance Bourjaily and playwright John Patrick drove ambulances in World War II for the American Field Service. But that seems to be the extent of famous author's association with wartime medical matters in other wars.

This raises several questions: Why did numerous future literary figures volunteer for ambulance work in the First World War? Why not in other wars? Did the ambulance work influence their later lives and their writing?

The answers to these questions tend to shed light on the times in which these writers lived and the changes which occurred in American society during the period of the First World War.

The Dismal Past

One good reason writers had not joined ambulance services in previous wars was a lack of such ambulance services to join.

Although military field hospitals and ambulance waggons were introduced by Queen Isabella's forces in the 1480's, the first organized field transport of wounded during battle in vehicles designed for that purpose did not take place until 1792, when Dominique-Jean Larrey, chief surgeon of the Grand Armee of France, created the first ambulance wagons specifically designed as ambulances. They had removable litters and places for storing bandaging supplies and refreshments. Larrey also designed a pack animal litter for wounded. His basic designs were used by armies worldwide until the advent of motorized ambulances about 100 years later.

There

were wagons used as ambulances in the American Civil War. At first

their reputation was bad. At Bull Run the ambulances were "driven by

civilian drunkards and thieves who ran when they heard the guns," one author

wrote. As the war progressed, Jonathan Letterman, medical director of

the Army of the Potomac, assigned specific ambulance corps to each army corps and ambulance

service was improved. The Japanese specifically used Letterman's

ambulance plan in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05) while the Russians did

not have an organized ambulance service.

There

were wagons used as ambulances in the American Civil War. At first

their reputation was bad. At Bull Run the ambulances were "driven by

civilian drunkards and thieves who ran when they heard the guns," one author

wrote. As the war progressed, Jonathan Letterman, medical director of

the Army of the Potomac, assigned specific ambulance corps to each army corps and ambulance

service was improved. The Japanese specifically used Letterman's

ambulance plan in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05) while the Russians did

not have an organized ambulance service.

Armies in general in the mid-nineteenth century were not noted for quality medical care. In 1869, Deputy Inspector-General T. Longmore, honorary surgeon to Queen Victoria, wrote in his A Treatise on the Transport of Sick and Wounded Troops that the ambulance systems were the least satisfactory part of the medical department, which itself was the least satisfactory part of the military.

A difficulty with ambulances was that a vehicle pulled by an animal was necessarily slow and, with the rough terrain usually found in battle areas, the patient was likely to die from the trip itself. It was more pathetic than glamorous. It was also under military discipline, a status many with artistic temperaments would find disagreeable.

A volunteer ambulance service, the Anglo-American Ambulance, was organized by American gynaecologist Marion Sims for service in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71).

A civilian volunteer ambulance corp. took six ox drawn ambulances to Cuba in 1898 to serve in The Spanish-American War. It arrived too late for action. The First New York Ambulance Society raised the money. American Red Cross founder Clara Barton went to Cuba to survey the needs and her nephew, Stephen Barton, shipped the ambulances.

As the nineteenth century came to an end, the image of the ambulance was about to undergo a radical change produced by the development of the automobile. In 1899 the first automobile ambulance in the world was built for a Chicago hospital. Soon speed was part of the image of the ambulance.

The Gentlemen Volunteers of World War I

This speed and the novelty of the ambulance helped make driving the vehicle acceptable to young members of the better educated class in the United States. This helps account for the nature of the organizations which recruited the volunteers and the type of volunteers they sought: gentlemen from the better schools.

The automobile was so new that many of the young men had to learn to drive before they could serve. "I'm going to France with the Norton-Harjes as soon as I can take a course in running a machine," wrote John Dos Passos in a personal letter.

There

were three predominant WWI volunteer ambulance groups: the American Field

Service (AFS), Norton-Harjes, and the American Red Cross operation in Italy.

There

were three predominant WWI volunteer ambulance groups: the American Field

Service (AFS), Norton-Harjes, and the American Red Cross operation in Italy.

When the United States entered the war, AFS and Norton-Harjes were both merged into the U.S. Army Ambulance Corps. Many of the future writers left the war rather than join the army where they would have become privates. In the volunteer groups they had been considered "gentlemen drivers" and the equivalent of officers. "Richard Norton is hanging on by his eye teeth," wrote E.E. Cummings to his mother on August 2, 1917, "God help us from being taken over by the American Army!!!!!!"

The only famous writer to serve only in the U.S. Army Ambulance Corps was Dashiell Hammett, who perhaps should not be included in the ambulance driver list. He is the only one on the list who did not volunteer for ambulance duty and the only one not to see service in Europe with the accompanying dangers. Hammett was assigned to an ambulance company after entering the U.S. Army, but he came down with tuberculosis and spent the war as a patient in a stateside hospital.

The American Field Service started as the ambulance arm of the American Hospital in Paris. Its driving force was A. Piatt Andrew, a former U.S. Assistant Secretary of the Treasury and professor of economics at Harvard University. A mid-1915 agreement resulted in the ambulances being attached to French line divisions.

The AFS got an eighteenth century mansion of five acres as headquarters and cut its ties with the American Hospital. AFS had recruited its drivers directly from colleges and universities around the United States. Individual ambulance units were made up exclusively of drivers from particular universities. Thus there were Harvard units, Yale units, etc.

The United States declared war on April 6, 1917 and AFS was merged into the U.S. Army on August 30, 1917. While serving as drivers with AFS 151 men had been killed, including 21 Harvard students. There were a total of about 2,500 AFS drivers in WWI. The AFS continued as a legal entity. It offered scholarships to France between the wars, provided ambulance service in France and North Africa in WWII, and since 1945 has operated a student exchange program.

The Norton-Harjes Ambulance Corps was created through the merger of the Harjes Formation of the American Red Cross and the American Volunteer Motor Ambulance Corps organized in 1914 by Richard Norton, son of Harvard's Charles Eliot Norton. Harjes was A. Herman Harjes, a French banker. Norton-Harjes reported no fatalities among its drivers.

The American Red Cross rushed 135 Americans to Italy in December 1917 to drive ambulances serving with the Italian Army.

Why Join?

Many young men had a strong desire to be in the middle of the action but were not physically fit for acceptance in an army. Hemingway, who had defective vision in his left eye, expressed these viewpoints when, prior to joining, he wrote to his sister, Marcelline, "But I'll make it to Europe some way in spite of this optic. I can't let a show like this go on without getting into it."

Dos Passos was so myopic he couldn't see the top letter on an eye chart. War was more dangerous than many thought. After getting wounded, a soldier might be sped off to the hospital by a half blind ambulance driver.

Somerset Maugham at 40 and 5'6" was both too old and too short to enlist at the beginning of the war. So he joined a British Red Cross ambulance unit attached to the French Army. One of his co-drivers, Desmond MacCarthy, later became literary critic for The Sunday Times.

Some

people failed to appreciate that these men entered the war before their

country did, risked death, and, in some cases, could not have gotten in the

military anyway.

Some

people failed to appreciate that these men entered the war before their

country did, risked death, and, in some cases, could not have gotten in the

military anyway.

The ambulance drivers were criticized for not being in fighting units. This disdain for non-combatants affected the viewpoints of some volunteers. Robert Service wrote that "I did not wear my Red Cross arm band, for I was ashamed I was not a combatant. Though I did not want to kill I was willing to take a chance of being killed. If I only could get some gore on my uniform I might feel better."

There were others who did not want to kill. Dos Passos was one of them. But Dos Passos in particular seemed not to mind chancing being killed. He took many chances far beyond the inherent risks of ambulance driving, which many considered risky enough.

Adventure, patriotism, doing what's right, signing up because others in the same school class signed up, and wanting to participate in what was of significance to the world at the time were all reasons for joining. So was escape. Dos Passos"s father had just died, preceded by his mother. He needed to get away. Harry Crosby considered his life at school and home unhappy and wanted to escape "the horrors of Boston and particularly of Boston virgins."

The reasons many of these same men returned to participate in Parisian literary circles in the 1920's were completely different from their reasons for entering the ambulance services. They returned to France after the war because it was cheaper to live there, France did not have prohibition, a wilder life could be led, Paris had the aura as the place to be for anyone artistic, there was less censorship, and France had become familiar to them from their time as ambulance drivers. Also the wild life in Paris could be an attempt to avoid facing what had been encountered in war.

Some expressed exuberance for the ambulance driving work. However, all the exuberance expressed may just have been to hide from the horrors being witnessed. Three of the American ambulance driver-authors who actually carried dead and dying committed suicide later in life: Hemingway, Crosby, and Seabrook. Although none of the suicides can be directly connected to the war, the proportion of suicides to the size of the group is very high and the war had an obviously strong influence on the lives of the men who later killed themselves.

Crosby's biographer Geoffrey Wolff wrote, "Mutilation, vermin, cowardice, relentlessness, insanity, hysteria, and cruelty played in the theatre of his imagination from the time of Verdun till the end of his life, and they were prompted by war."

Cowley believed Crosby's suicide related specifically to November 22, 1917, when a shell seriously wounded a man standing beside Crosbyand then, as he drove some of the wounded from the area, shells continued to burst all around his ambulance. Crosby himself said it was that night that changed him from a boy into a man.

Could that be true not only regarding Crosbybut also in regard to Seabrook and to Hemingway? Hemingway was seriously wounded by a shell which killed men near him.

War in Writings

The First World War played a major role in the writings of the men who served in that war's volunteer ambulance corps. War can provide the basic impetus that gets a person started toward becoming a writer.

But most soldiers don't have the leisure to contemplate the fundamental elements war can bring a person face to face with. But being an ambulance driver by its very nature made a person feel more like a spectator than a participant.

There were times to think while ambulance driving or while waiting to drive. Thoughts lead naturally to the desire to put those thoughts on paper.

One thing Maugham did while idling near Dunkirk was correct the proofs of his novel Of Human Bondage.

Principal characters in Dos Passos' 1919 follow his own history of serving first with Norton-Harjes in France then with The American Red Cross in Italy. The 42nd Parallel had ended with its main character headed to France to drive an ambulance. His first novel, One Man's Initiation, 1917, was about the war.

The primary character in Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms like Hemingway himself is wounded while serving as an ambulance driver in Italy and falls in love with his nurse in the hospital. Both Dos Passos and Hemingway returned later in their writing to WWI.

Robert Service's Rhymes of a Red Cross Man were derived from his own experience. The Enormous Room by E.E. Cummings was about his time in a French prison.

Charles Nordhoff began his writing career when his accounts of his ambulance service were published in The Atlantic Monthly. His co-author of Mutiny on the Bounty, Charles Norman Hall, served in the Lafayette Escadrille and also wrote accounts of the war for The Atlantic Monthly.

Gertrude Stein wrote about her WWI work in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas.

Dorothea Canfield Fisher wrote simple stories in Braille for blinded French soldiers. She also wrote Home Fires and The Day of Glory about the war.

John Masefield wrote The Old Front Line and The Battle of the Somme.

The

war helped produce an international group of wanderers. The tradition

had been broken of settling down to work and family after finishing formal

education.

The

war helped produce an international group of wanderers. The tradition

had been broken of settling down to work and family after finishing formal

education.

The former ambulance drivers could not seem to keep still. Dos Passos bounced all over the place. Hemingway kept going back to France, Italy, and Spain. Seabrook was perhaps the most exotic traveller, living with North African Bedouins, with devil worshipers in Kurdistan, and with voodoo believers in Haiti. Sidney Howard served in ambulance corps both in France and in the Balkans. Later he translated works from Spanish, French, German, and Hungarian.

When the writers did go home, it was with thoughts of travel, excitement, and war in their minds, pens, and Smith-Coronas. And they found they could not stay home.

"We literary men have been very evil, writing about war," wrote Masefield in a letter to his wife early in the war, "To fight is bad enough, but it has its manly side, but to let the mind dwell on it and peck its carrion and write of it is a devilish, unmanly thing, and that's what we've been doing, ever since we had leisure, circa 1850."

The literary generation of the war became the first true generation of American writers. But it was a generation adrift; first into the alcoholism and sexual freedom of the 1920's and then into the radicalism of the 1930's.

Instead of a derivative European voice or a regional voice, America had grown to the maturity of having a national literature. Ambulance service in WWI had helped to mould the outlook of that literary generation. They in turn helped mould the outlook of future American generations.

Writers Who Were Ambulance Drivers in WWI

- Ernest Hemingway

- John Dos Passos

- E.E. Cummings

- Somerset Maugham

- John Masefield

- Malcolm Cowley

- Sidney Howard

- Robert Service

- Louis Bromfield

- Harry Crosby

- Julian Green

- Dashiell Hammett

- William Seabrook

- Robert Hillyer

- John Howard Lawson

- William Slater Brown

- Charles Nordhoff

- Sir Hugh Walpole

- Desmond MacCarthy

- Russell Davenport

- Edward Weeks

- C. Leroy Baldridge

- Samuel Chamberlain

Related Occupation

- Gertrude Stein, visited hospitals and drove for American Fund for French Wounded)

- Marjory Stoneman Douglas, worked at American Red Cross headquarters in Paris because she was in love with an ambulance driver

- E.M. Forster, interviewed wounded in Egyptian hospitals

- Dorothea Francis Canfield Fisher, made home in France for husband while he was ambulance driver

- Archibald Cronin, doctor

- Edmund Wilson, stretcher bearer

- Anne Green, nurse

Article contributed by

Steve Ruediger

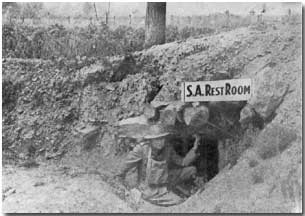

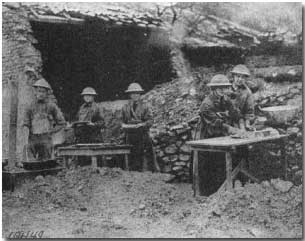

Photographs courtesy of Photos of the Great War website.

Both British and German fleets had around 45 submarines available at the time of the Battle of Jutland, but none were put to use.

- Did you know?