Primary Documents - Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg on the Italian Declaration of War, 23 May 1915

Reproduced below is the

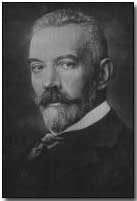

formal reaction of German Chancellor

Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg

to news that Italy had finally abandoned her

policy of neutrality and

entered

the war against the Central Powers on 23 May 1915.

Reproduced below is the

formal reaction of German Chancellor

Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg

to news that Italy had finally abandoned her

policy of neutrality and

entered

the war against the Central Powers on 23 May 1915.

Given Italy's earlier alliance with both Germany and Austria-Hungary an indignant reaction from both countries was to be expected; in the event Italy had also negotiated a secret treaty with the Allies in London in April 1915 which promised sizeable territorial gains for Italy were she to join the Allied cause.

Click here to read Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Josef I's reaction to the Italian declaration.

Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg on the Italian Declaration of War

When I last spoke there was still a glimpse of hope that Italy's participation in the war could be avoided.

That hope proved fallacious. German feeling strove against the belief in the possibility of such a change. Italy has now inscribed in the book of the world's history, in letters of blood which will never fade, her violation of faith.

I believe Machiavelli once said that a war which is necessary is also just. Viewed from this sober, practical, political standpoint, which leaves out of account all moral considerations, has this war been necessary? Is it not, indeed, directly mad?

Nobody threatened Italy; neither Austria-Hungary nor Germany. Whether the Triple Entente was content with blandishments alone history will show later. Without a drop of blood flowing, and without the life of a single Italian being endangered, Italy could have secured the long list of concessions which I recently read to the House - territory in Tyrol and on the Isonzo as far as the Italian speech is heard, satisfaction of the national aspirations in Trieste, a free hand in Albania, and the valuable port of Valona.

Why have they not taken it? Do they, perhaps, wish to conquer the German Tyrol? Hands off! Did Italy wish to provoke Germany, to whom she owes so much in her upward growth of a great power, and from whom she is not separated by any conflict of interests?

We left Rome in no doubt that an Italian attack on Austro-Hungarian troops would also strike the German troops. Why did Rome refuse so light-heartedly the proposals of Vienna? The Italian manifesto of war, which conceals an uneasy conscience behind vain phrases, does not give us any explanation. They were too shy, perhaps, to say openly what was spread abroad as a pretext by the press and by gossip in the lobbies of the Chamber, namely, that Austria's offer came too late and could not be trusted.

What are the facts? Italian statesmen have no right to measure the trustworthiness of other nations in the same proportion as they measured their own loyalty to a treaty. Germany, by her word, guaranteed that the concessions would be carried through. There was no occasion for distrust. Why too late? On May 4th the Trentino was the same territory as it was in February, and a whole series of concessions had been added to the Trentino of which nobody had thought in the winter.

It was, perhaps, too late for this reason, that while the Triple Alliance, the existence of which the King and the Government had expressly acknowledged after the outbreak of war, was still alive, Italian statesmen had long before engaged themselves so deeply with the Triple Entente that they could not disentangle themselves.

There were indications of fluctuations in the Rome Cabinet as far back as December. To have two irons in the fire is always useful. Before this Italy had shown her predilection for extra dances, but this is no ballroom. This is a bloody battlefield upon which Germany and Austria-Hungary are fighting for their lives against a world of enemies. The statesmen of Rome have played against their own people the same game as they played against us.

It is true that the Italian-speaking territory on the northern frontier has always been the dream and the desire of every Italian, but the great majority of the Italian people, as well as the majority in Parliament, did not want to know anything of war. According to the observation of the best judge of the situation in Italy, in the first days of May 4th-5th of the Senate and two-thirds of the Chamber were against war, and in that majority were the most responsible and important statesmen.

But common sense had no say. The mob alone ruled. Under the kindly disposed toleration and with the assistance of the leading statesmen of a Cabinet fed with the gold of the Triple Entente, the mob, under the guidance of unscrupulous war instigators, was roused to a frenzy of blood which threatened the King with revolution and all moderate men with murder if they did not join in the war delirium.

The Italian people were intentionally kept in the dark with regard to the course of the Austrian negotiations and the extent of the Austrian concessions, and so it came about that after the resignation of the Salandra Cabinet nobody could be found who had the courage to undertake the formation of a new Cabinet, and that in the decisive debate no member of the Constitutional Party in the Senate or Chamber even attempted to estimate the value of the far-reaching Austrian concessions.

In the frenzy of war honest politicians grew dumb, but when, as the result of military events (as we hope and desire), the Italian people become sober again it will recognize how frivolously it was instigated to take part in this world war.

We did everything possible to avoid the alienation of Italy from the Triple Alliance. The ungrateful role fell to us of requiring from our loyal ally, Austria, with whose armies our troops share daily wounds, death, and victory, the purchase of the loyalty of the third party to the alliance by the cession of old-inherited territory.

That Austria-Hungary went to the utmost limit possible is known. Prince von Bulow, who again entered into the active service of the empire, tried by every means, his diplomatic ability, his most thorough knowledge of the Italian situation and of Italian personages, to come to an understanding.

Though his work has been in vain, the entire people are grateful to him. Also this storm we shall endure. From month to month we grow more intimate with our ally. From the Pilitza to the Bukowina we tenaciously withstood with our Austro-Hungarian comrades for months the gigantic superiority of the enemy. Then we victoriously advanced.

So our new enemies will perish through the spirit of loyalty and the friendship and bravery of the central powers. In this war Turkey is celebrating a brilliant regeneration. The whole German people follow with enthusiasm the different phases of the obstinate, victorious resistance with which the loyal Turkish Army and fleet repulse the attacks of their enemies with heavy blows. Against the living wall of our warriors in the west our enemies up till now have vainly stormed.

If in some places fighting fluctuates, if here or there a trench or a village is lost or won, the great attempt of our adversaries to break through, which they announced five months ago, did not succeed, and will not succeed. They will perish through the heroic bravery of our soldiers.

Up till now our enemies have summoned in vain against us all the forces of the world and a gigantic coalition of brave soldiers. We will not despise our enemies, as our adversaries like to do. At the moment when the mob in English towns is dancing around the stake at which the property of defenceless Germans is burning, the English Government dared to publish a document, with the evidence of unarmed witnesses, on the alleged cruelties in Belgium, which are of so monstrous a character that only mad brains could believe them.

But while the English press does not permit itself to be deprived of news, the terror of the censorship reigns in Paris. No casualty lists appear, and no German or Austrian communiqués may be printed. Severely wounded invalids are kept away from their relations, and real fear of the truth appears to be the motive of the Government.

Thus it comes about, according to trustworthy observation, that there is no knowledge of the heavy defeats which the Russians have sustained, and the belief continues in the Russian "steam-roller" advancing on Berlin, which is "perishing from starvation and misery," and confidence exists in the great offensive in the west, which for months has not progressed.

If the Governments of hostile States believe that by the deception of the people and by unchaining blind hatred they can shift the blame for the crime of this war and postpone the day of awakening, we, relying on our good conscience, a just cause, and a victorious sword, will not allow ourselves to be forced by a hair's breadth from the path which we have always recognized as right. Amid this confusion of minds on the other side, the German people goes on its own way, calm and sure.

Not in hatred do we wage this war, but in anger - in holy anger. The greater the danger we have to confront, surrounded on all sides by enemies, the more deeply does the love of home grip our hearts, the more must we care for our children and grandchildren, and the more must we endure until we have conquered and have secured every possible real guarantee and assurance that no enemy alone or combined will dare again a trial of arms.

The more wildly the storm rages around us the more firmly must we build our own house. For this consciousness of united strength, unshaken courage, and boundless devotion, which inspire the whole people, and for the loyal cooperation which you, gentlemen, from the first day have given to the Fatherland, I bring you, as the representatives of the entire people, the warm thanks of the Emperor.

Source: Source Records of the Great War, Vol. III, ed. Charles F. Horne, National Alumni 1923

By 1918 the percentage of women to men working in Britain had risen to 37% from 24% at the start of the war.

- Did you know?