Memoirs & Diaries - The Retreat from Mons, August 23rd-September 5th, 1914

August 23rd

August 23rd

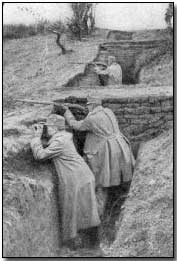

We had been marching since 2.30 a.m. and about 11.15 a.m. an order was passed down for "A" Company (my company) to deploy to the right and dig in on the south bank of a railway cutting. We deployed and started digging in, but as the soil was mostly chalk, we were able to make only shallow holes.

While we were digging the German artillery opened fire. The range was perfect, about six shells at a time bursting in line directly over our heads.

All of us except the company commander fell flat on our faces, frightened, and surprised; but after a while we got up, and looked over the rough parapet we had thrown up; and could not see much. One or two men had been wounded, and one was killed.

There was a town about one mile away on our left front, and a lot of movement was going on round about it; and there was a small village called Binche on our right, where there was a lot of heavy firing going on - rifle and artillery.

We saw the Germans attack on our left in great masses, but they were beaten back by the Coldstream Guards. A squadron of German cavalry crossed our front about 800 yards distant, and we opened fire on them. We hit a few and the fact that we were doing something definite improved our moral immensely, and took away a lot of our nervousness.

The artillery fire from the Germans was very heavy, but was dropping behind us on a British battery. The company officer, who had stayed in the open all the time, had taken a couple of men to help get the wounded away from the battery behind us. He returned about 6.30 p.m., when the firing had died down a bit, and told us the battery had been blown to bits.

I

was then sent with four men on outpost to a signal box at a level crossing,

and found it was being used as a clearing station for wounded.

I

was then sent with four men on outpost to a signal box at a level crossing,

and found it was being used as a clearing station for wounded.

After dark more wounded were brought in from the 9th Battery R.F.A. (the battery that was cut up).

One man was in a very bad way, and kept shrieking out for somebody to bring a razor and cut his throat, and two others died almost immediately. I was going to move a bundle of hay when someone called out, "Look out, chum. There's a bloke in there." I saw a leg completely severed from its body, and suddenly felt very sick and tired.

The German rifle-fire started again and an artillery-man to whom I was talking was shot dead. I was sick then. Nothing much happened during the night, except that one man spent the time kissing a string of rosary beads, and another swore practically the whole night.

August 24th

Just about dawn a party of Germans came near and we opened fire on them and hit quite a number. We thought of following them up, but a corporal brought an order to retire. We joined the company again behind the trenches, and learnt that the town we could see was Mons.

After a while we joined up with the rest of the battalion on the road and went back the same route we covered coming up. All the time there was plenty of firing going on by Givry, and about midday we deployed, and opened fire on a regiment of German cavalry.

They dismounted and returned our fire, which was all "rapid" and was telling on them. Then suddenly they mounted and disappeared out of range. We continued marching back for about four hours. Then again we deployed and opened fire on more German cavalry, but this time they kept out of range and eventually moved off altogether.

My

platoon was sent forward to a small village, where we stayed all night

firing occasionally at what we hoped were German cavalry.

My

platoon was sent forward to a small village, where we stayed all night

firing occasionally at what we hoped were German cavalry.

August 25th

We started off about 5 a.m., still retiring, and so far we had had no food since Sunday the 23rd.

All day long we marched, and although a lot of firing was going on, we did none of it.

About 6.30 p.m. we got to a place called Maroilles, and my platoon spent the night guarding a bridge over a stream.

The Germans attacked about 9 p.m. and kept it up all night, but didn't get into Maroilles.

About forty-five of the company were killed or wounded, including the company officer. A voice had called out in English, "Has anybody got a map?" and when our C.O. stood up with his map, a German walked up, and shot him with a revolver. The German was killed by a bayonet stab from a private.

August 26th

The Germans withdrew at dawn, and soon after we continued retiring, and had not been on the march very long before we saw a French regiment, which showed that all of them had not deserted us.

We marched all day long, miles and miles it seemed, probably owing to the fact that we had had no sleep at all since Saturday the 22nd, and had had very little food to eat, and the marching discipline was not good. I myself frequently felt very sick.

We had a bit of a fight at night, and what made matters worse was that it happened at Venerolles, the village we were billeted in before we went up to Mons. Anyway, the Germans retired from the fight.

August 27th

At dawn we started on the march again. I noticed that the cure and one old fellow stayed in Venerolles, but all the other inhabitants went the previous night. A lot of our men threw away their overcoats while we were on the road to-day, but I kept mine.

The

marching was getting quite disorderly; numbers of men from other regiments

were mixed up with us. We reached St. Quentin, a nice town, just

before dark, but marched straight through, and dug ourselves in on some high

ground, with a battery of artillery in line with us.

The

marching was getting quite disorderly; numbers of men from other regiments

were mixed up with us. We reached St. Quentin, a nice town, just

before dark, but marched straight through, and dug ourselves in on some high

ground, with a battery of artillery in line with us.

Although we saw plenty of movement in the town the Germans didn't attack us, neither did we fire on them. During the night a man near me quite suddenly started squealing like a pig, and then jumped out of the trench, ran straight down the hill towards the town, and shot himself through the foot. He was brought in by some artillery-men.

August 28th

Again at dawn we started on the march, and during the first halt another fellow shot himself through the foot. The roads were in a terrible state, the heat was terrific, there seemed to be very little order about anything, and mixed up with us and wandering about all over the road were refugees, with all sorts of conveyances - prams, trucks, wheelbarrows, and tiny little carts drawn by dogs.

They were piled up, with what looked like beds and bedding, and all of them asked us for food, which we could not give them, as we had none ourselves.

The men were discarding their equipment in a wholesale fashion, in spite of orders to the contrary; also many of them fell out, and rejoined again towards dusk. They had been riding on limbers and wagons, and officers' chargers, and generally looked worse than those of us who kept going all day.

That night I went on outpost, but I did not know where exactly, as things were getting hazy in my mind. I tried to keep a diary, although it was against orders. Anyway, I couldn't realize all that was happening, and only knew that I was always tired, hungry, unshaven, and dirty.

My feet were sore, water was scarce: in fact, it was issued in half-pints, as we were not allowed to touch the native water. The regulations were kept in force in that respect - so much so that two men were put under arrest and sentenced to field punishment for stealing bread from an empty house.

Then,

again, it wasn't straight marching. For every few hours we had to

deploy, and beat off an attack, and every time somebody I knew was killed or

wounded. And after we had beaten off the attacking force, on we went

again - retiring.

Then,

again, it wasn't straight marching. For every few hours we had to

deploy, and beat off an attack, and every time somebody I knew was killed or

wounded. And after we had beaten off the attacking force, on we went

again - retiring.

August 29th

A despatch was read to us, from General French, explaining that the B.E.F. was on the west of a sort of horseshoe, and that the retirement was to draw the Germans right into it, when they would be nipped off.

That afternoon we went to a place called Chauny to guard the river while some R.E.'s blew up the bridges. It was a change from the everlasting marching, and we managed to get some vegetables out of the gardens and cook them.

A few Uhlans appeared, but got away again in spite of our fire. So far as I could tell there wasn't a single civilian in the town, and all the houses were barricaded; while outside of them were buckets of wine - pink, blue, red, whitish, and other colours. We were not allowed to drink any.

August 30th

Just as we were leaving Chauny - about 4 a.m. - two girls were found and were taken along with us.

Although all the bridges were blown up, the Germans were after us almost immediately. God only knew how they got over so soon. Their fire was heavy but high; the few we saw were firing from their hips as they advanced.

We fired for about half an hour. Then the artillery came into action, and we retired about two or three miles under cover of their fire. Then we waited till the Germans came up, and we began all over again, and then again, and then again, all day long. It was terribly tiring, heart-breaking work, as we seemed to have the measure of the Germans, and yet we retired.

During the evening the Guards Brigade took over the rearguard work while our Brigade went on to Castle Isoy, and bivouacked and slept for about six hours.

August 31st

Again we were rearguard, but did little fighting. We marched instead, staggering about the road like a crowd of gipsies. Some of the fellows had puttees wrapped round their feet instead of boots; others had soft shoes they had picked up somewhere; others walked in their socks, with their feet all bleeding.

My

own boots would have disgraced a tramp, but I was too frightened to take

them off, and look at my feet.

My

own boots would have disgraced a tramp, but I was too frightened to take

them off, and look at my feet.

Yet they marched until they dropped, and then somehow got up and marched again.

One man (Ginger Gilmore) found a mouth-organ, and, despite the fact that his feet were bound in blood-soaked rags, he staggered along at the head of the company playing tunes all day. Mostly he played "The Irish Emigrant," which is a good marching tune. He reminded me of Captain Oates.

An officer asked me if I wanted a turn on his horse, but I looked at the fellow on it, and said, "No thanks".

The marching was getting on everyone's nerves, but, as I went I kept saying to myself, "If you can, force your heart and nerve and sinew." Just that, over and over again.

That night we spent the time looking for an Uhlan regiment, but didn't get in touch with them, and every time we stopped we fell asleep; in fact we slept while we were marching, and consequently kept falling over.

September 1st

We continued at the same game from dawn till dark, and dark till dawn - marching and fighting and marching. Every roll call there were fewer to answer - some were killed, some wounded, and some who had fallen out were missing.

During this afternoon we fought for about three hours - near Villers-Cotterets I think it was, but I was getting very mixed about things, even mixed about the days of the week. Fifteen men in my company were killed, one in a rather peculiar fashion.

He was bending down, handing me a piece of sausage, and a bullet ricocheted off a man's boot and went straight into his mouth and out of the top of his head.

We

got on to the road about 200 yards only in front of a German brigade, and

then ran like hell for about a mile, until we passed through the South

Staffs Regiment, who were entrenched each side of the road. I believe

about six of the battalion were captured.

We

got on to the road about 200 yards only in front of a German brigade, and

then ran like hell for about a mile, until we passed through the South

Staffs Regiment, who were entrenched each side of the road. I believe

about six of the battalion were captured.

Still we marched on until dusk, then on outpost again, and during the night the South Staffs passed through us.

September 2nd

At 2 a.m. we moved off, and marched all day long. It was hot and dusty and the roads were rotten, but, as we got mixed up with hundreds of refugees, we were obliged to keep better marching order. About 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. we reached Meaux - I believe we did about twenty-five miles that day, but no fighting.

We bivouacked outside Meaux, but I went into the cathedral when we halted near it, and thought it was very beautiful. Also I saw some of the largest tomatoes I have ever seen in my life, growing in a garden. I was rounding up stragglers most of the night until 1 a.m., and at 3 a.m. we moved off again.

September 3rd

The first four or five hours we did without a single halt or rest, as we had to cross a bridge over the Aisne before the R.E.'s blew it up. It was the most terrible march I have ever done. Men were falling down like nine-pins. They would fall fiat on their faces on the road, while the rest of us staggered round them, as we couldn't lift our feet high enough to step over them, and, as for picking them up, that was impossible, as to bend meant to fall.

What happened to them, God only knows. An aeroplane was following us most of the time dropping iron darts; we fired at it a couple of times, but soon lost the strength required for that. About 9 a.m. we halted by a river, and immediately two fellows threw themselves into it.

Nobody, from sheer fatigue, was able to save them, although one sergeant made an attempt, and was nearly drowned himself.

I,

like a fool, took my boots off, and found my feet were covered with blood.

I could find no sores or cuts, so I thought I must have sweated blood.

I,

like a fool, took my boots off, and found my feet were covered with blood.

I could find no sores or cuts, so I thought I must have sweated blood.

As I couldn't get my boots on again I cut the sides away, and when we started marching again, my feet hurt like hell.

We marched till about 3 p.m. - nothing else, just march, march, march. I kept repeating my line, ..If you can, force, etc." Why, I didn't know. A sergeant irritated everyone who could hear him by continually shouting out: "Stick it, lads. We're making history."

The Colonel offered me a ride on his horse, but I refused, and then wished I hadn't, as anything was preferable to the continuous marching.

We got right back that afternoon among the refugees again. They were even worse off than we were, or, at least, they looked it. We gave the kids our biscuits and "bully," hoping that would help them a little; but they looked so dazed and tired there did not seem to be much hope for them. At 8 p.m. we bivouacked in a field and slept till dawn. Ye gods! what a relief.

September 4th

I was sent with six men on outpost to a small wood on our left front, and I had not posted the sentries more than half an hour, before an officer found two of them asleep. The poor fellows were afterwards tried by courts martial and shot.

About 3 p.m. we all moved off again, and came into action almost immediately, although I believe it was a food convoy that was mistaken for German artillery by our artillery. Anyway no one I knew was hurt. It was said, however, that Jerry rushed his troops along after us in lorries.

All through the night we marched, rocking about on our feet from the want of sleep, and falling fast asleep even if the halt lasted only a minute. Towards dawn we turned into a farm, and for about two hours I slept in a pigsty.

I noticed the same thing about that farm that I'd noticed about most French farms. That was, although they seemed more intensively cultivated than English farms, the farm implements were very old-fashioned.

September 5th

Early on this morning reinforcements from England joined us, and the difference in their appearance and ours was amazing. They looked plump, clean, tidy, and very wide-awake. Whereas we were filthy, thin, and haggard.

Most

of us had beards; what equipment was left was torn; instead of boots we had

puttees, rags, old shoes, field boots - anything and everything wrapped

round our feet.

Most

of us had beards; what equipment was left was torn; instead of boots we had

puttees, rags, old shoes, field boots - anything and everything wrapped

round our feet.

Our hats were the same, women's hats, peasants' hats, caps, any old covering, while our trousers were mostly in ribbons.

The officers were in a similar condition. After the reserves joined we marched about twenty miles to a place called Chaumes. It was crowded with staff officers. We bivouacked in a park, and then had an order read to us that the men who had kept their overcoats were to dump them, as we were to advance at any moment. Strangely, a considerable amount of cheering took place then.

I discovered that the company I was in covered 251 miles in the Retreat from Mons, which finished on September 5th, 1914.

Corporal Bernard John Denore, 1st Royal Berks Regt., 6th Brigade, 2nd Division, I Army Corps. In Action at Battle of and Retreat from Mons; Battle of the Marne; the Aisne (about two months); First Battle of Ypres; in the Salient four weeks.

Wounded at Zonnebeke (in seven places); in hospital at Boulogne, London, and Reading.

First published in Everyman at War (1930), edited by C. B. Purdom.

Photographs courtesy of Photos of the Great War website.

The "linseed lancers" was the Anzac nickname assigned to members of the Australian Field Ambulance.

- Did you know?