Memoirs & Diaries - A Wireless Operator

At the age of eighteen I

crossed to France early in 1917, a sapper in the Royal Engineers Wireless

Section. We operators had only a vague idea of our likely duties, for

the Wireless Section was only then becoming of use in the trenches.

At the age of eighteen I

crossed to France early in 1917, a sapper in the Royal Engineers Wireless

Section. We operators had only a vague idea of our likely duties, for

the Wireless Section was only then becoming of use in the trenches.

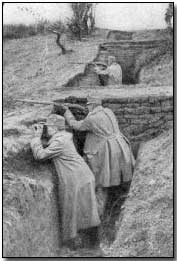

I was sent via St. Pol to Arras, and with a fellow-operator was led into the trenches at Roclincourt. There I first experienced the bursting of a shell near me, and I laughed at the frightened manner in which our guide flung himself down when the shell fell about thirty yards away. It was not long before I took to flinging myself down on such occasions.

When our guide led me into a trench filled waist deep with muddy water, I could not believe he was serious - and I hesitated - I was wearing brand-new riding-breeches, puttees, and boots. However, I waded in, and it was seventeen days before my boots touched dry soil again.

We were left in a muddy dug-out at Roclincourt with an officer and his batman, waiting for the attack. We spent our time experimenting with a small British Field set - the Trench set - and we still had no idea of our purpose.

Then, on April 5th, we were called into Arras where a R.E. officer "put us wise". The attack was to be made within the next few days, the infantry waves were to advance under cover of a formidable barrage, and each wave was to be provided with a wireless station. The Roclincourt station was to go over with the first infantry wave.

The Roclincourt station! That was Hewitt and I and an officer! Four infantrymen were to assist us in carrying our weighty apparatus, the set, accumulators, dry cells, coils of wire, earth mats, ropes, and other details.

We returned to Roclincourt and sent many practice messages to our Directing Station at Arras. That night one of our aerial masts was shattered and we were instructed to erect another. We had no reserve mast, but, fortunately, we found a large crucifix nearby.

"That's it," said the officer. "Hewitt, climb up there and attach the aerial as high as possible."

Hewitt clambered up over the figure of Christ just as a German machine gun swept the line, the Verey lights revealing Hewitt distinctly. He soon fell into a depth of slime, frightened, but unhurt. It was our first experience of enemy machine-gun fire.

"You try," the officer pointed to me.

It is an eerie sensation to

climb over an effigy of Jesus, to dig your feet into any parts of the figure

offering foothold, to hold on to the outstretched arms, and breathe on to

the downcast face, to fix a rope somewhere on the Cross and to hear the

German machine gun tat-tatting all around.

It is an eerie sensation to

climb over an effigy of Jesus, to dig your feet into any parts of the figure

offering foothold, to hold on to the outstretched arms, and breathe on to

the downcast face, to fix a rope somewhere on the Cross and to hear the

German machine gun tat-tatting all around.

Failing to secure the rope, I slid down and we returned to the dug-out with our officer extremely annoyed. Early the next morning we secured the aerial to the ruins of a building. On April 7th our officer laid a plan of the German sector opposite us on the table, and he detailed our instructions.

At a particular tree-stump far over in the enemy's Blue Line we were to erect a station as rapidly as possible and transmit any messages handed in by the officers engaged in the attack.

I felt intensely relieved that I was to be given an opportunity of doing something useful, and of feeling that at last I was to playa real part in the Great War. I found that Hewitt, too, experienced this sense of relief.

On the evening of the 7th some letters came up. There was one from my father telling me he had bought a new bicycle, a Raleigh, for "when I came home". It affected me strangely, and when I mentioned the new cycle in the dug-out, our officer grunted "some hopes!" When I considered our immediate future I must have echoed the sentiment.

Our officer's nerves were rather frayed that evening. Perhaps in the infantry he had led many attacks, perhaps he had been badly knocked about before he came to us. We didn't know; nobody seemed to know much about him.

Through the night we waited for the signal. One o'clock, two, three, four (or was it five?) ...the barrage started! A roar all along the line. Then suddenly, with a similar "snap" to that with which it started, the barrage stopped. Sunday, April 8th, dawned and passed without the attack having been made. Had a change of plans taken place?

Sunday night - further infantry poured into the trenches, slowly, nervously, pressing along. All was tense... no laughter, no jesting, no conversation. There was no doubt that the attack would take place on the morrow.

All night the muddied figures stood outside our dug-out; inside we sat, each with his load close at hand. Apart from wireless material we carried ground sheets, rifles (unloaded!) I bandoliers, each holding fifty rounds, gas masks, iron rations, and our clothes.

At 3.30 a.m. we went out into the trenches, eight in all: the officer, his batman, two operators, and four infantry carriers. We threaded our way along the crowded trenches as best we could until we reached a company of Tyneside Scottish. There we waited.

The silence remained tense, more awful than ever. Everyone "standing to" awaiting the barrage and the signal!

4 a.m. The barrage opened with a mighty roar and there it fell incessantly just across the waste. "Go!"

Over the top we clambered,

over the stricken wilderness we stumbled. We wireless "merchants"

mixed with the infantry, hoping for some protection.

Over the top we clambered,

over the stricken wilderness we stumbled. We wireless "merchants"

mixed with the infantry, hoping for some protection.

We carried no bayonets, our unloaded rifles were strapped across our backs and our only means of defence was apparently fists. Why wireless operators were not allowed to load their rifles we never learned.

We attained the enemy lines. Jerry was engaged in peaceful domestic functions! Some washing, others making coffee, and many had to be awakened to be taken captive. The blow had fallen before they expected it.

It was not long, however, before the German defences, the colossal barrage tearing into their supports, were roused to a fierce retaliation. Heroic and desperate Germans mounted machine guns, and knowing they could not withstand our onslaught they exacted a heavy toll for their own lives.

One enemy sergeant I saw shot twenty of ours before he was bayoneted in his back. Then a rain of spluttering ferocious shrapnel fire came over from the German artillery and "heavy stuff" crashed into us.

The waves of our infantry became somewhat disorganized owing to the difficulty of moving over the heavy, pitted land and to the congestion of the German prisoners, who were dazed by their good fortune in being taken.

The second wave passed - the third - the fourth, and soon the well-defined waves were indistinguishable.

We wireless "Blokes" struggled on with our burdens, aiming, of course, for the tree-stump by the Blue Line. When daylight came we found we were only seven - our officer, carrying no burden, had hurried on with the leading infantry-men.

Through the hours we continued stumbling, sinking, slipping, into old trenches, shell holes, all the time in the midst of a scattered but advancing infantry.

Noon - we still struggled, overburdened with wireless parts. The wounded were limping or being carried in, the thousands of prisoners formed long, straggling processions, the dead lay unnoticed.

At 12.30 we reached the tree-stump. Our officer stood in a deep trench scowling at us.

"Get into communication at once, I have messages here." He waved a sheaf of papers in his hand.

Hewitt

and I immediately set about erecting a 60-yard aerial on 18-foot masts.

It was an uneasy task erecting this fully exposed to the vicious enemy fire.

Actually I counted afterwards ten men who had been killed outright by

shrapnel near us, as we secured the masts.

Hewitt

and I immediately set about erecting a 60-yard aerial on 18-foot masts.

It was an uneasy task erecting this fully exposed to the vicious enemy fire.

Actually I counted afterwards ten men who had been killed outright by

shrapnel near us, as we secured the masts.

Presently we dropped into the dug-out allotted us and we tuned in for our D.S. I was told to operate. At length I heard D.S. "Wait," he said. He was dealing with early morning codes from other corps.

At length I seized my turn and transmitted as many messages as I could before I lost my priority. I continued sending messages at intervals (but listening-in all the time) until 8 p.m., when our work died down, land-line communication having been established.

But the officer forbade me to get up.

"Continue listening-in. Hewitt will relieve you at midnight".

So I sat huddled on a box in a narrow tunnel with the candle-lit set before me and the telephones tightly gripping my ears. In the dug-out the officer, his batman, and Hewitt sat, while in a stifling den underneath the dug-out the four infantrymen rested.

On this part of the Hindenburg line the trenches were "double-deckers". Sometimes my back touched the clay wall behind me, and my eyes; when turned from the set, blinked into clay - clay everywhere. Two candles flickered above the set, resting on bayonets stabbed into the clay.

Just on the side of the set, away from the dug-out, the tunnel had been shelled, and it opened into the yawning shell hole. Deep in this a young, handsome Tyneside Scottish soldier lay dead. His feet pointed upwards, his body lay on his back with his face upturned. He was not more than five yards from me.

The

night air became chill and the rain drizzled. I asked Hewitt to string

up some sacking.

The

night air became chill and the rain drizzled. I asked Hewitt to string

up some sacking.

I wanted it for two reasons - to reduce the draught and to help me forget the dead soldier lying there. Presently the others curled themselves up, and their snores soon assured me that they were asleep. I remained listening-in for a possible emergency call.

10.30 p.m. An eerie silence on the ether, pierced only by atmospherics crackling in my ears. As the time went on the strange quietude became ghastly, and all the time, the Tyneside soldier lay there, just the other side of the sack, his eyes probably still gazing blindly to the darkened skies.

A wind sprang up, blowing The sacking in towards me, as though some enfeebled soul pressed against it. Sometimes the wind lifted a corner of the sack, and I peered through into the darkened shell hole.

The rain became sleet, and it turned to snow. I knew because the snow soon attained sufficient weight to bear down lumps of earth, and fugitive flakes drifted into the tunnel.

12 o'clock. Hewitt's turn! Was it worth his listening-in? Perhaps I would get instructions to close down any minute... pity to wake him! I decided to continue the watch myself. (I should have stated before that Hewitt suffered from cramp in his right elbow and our officer had no confidence in his operating, hence the long watch that fell to me.)

1 o'clock. I was really cold now. Snow and mud rolled into the tunnel from the shell hole, and the sacking became insecure. And then D.S. told me to close down.

I tried to sleep, but my weird imprisonment in the tunnel had disturbed me. I could not sleep... perhaps the Tyneside soldier prevented it.

I

suppose I dozed, for I awoke to find faint gleams of daylight peeping down

the stairway.

I

suppose I dozed, for I awoke to find faint gleams of daylight peeping down

the stairway.

The others were soundly asleep. I got up and went outside.

A snow-covered wilderness!

All was still. Not a gun shot, not a voice, not a living person in sight.

The sun was about to rise, and I watched fascinated.

As the yellow sun became flushed so the disappearing snow revealed the toll - the countless black lumps lying everywhere in the mud. The snow soon thawed on the Tyneside soldier, and he seemed as tragically beautiful as he had appeared the previous day.

The silence continued. The silence of a winter morning in the fields of Gloucestershire. Where the war of yesterday?

The sun soon sipped up all traces of the snow, and all was naked again - shambles, mud, desolation!

Silence, profound, unreal.

Then suddenly as though from nowhere a faint, lazy, approaching whistle-bang! A big German shell burst at my back.

The spell was ended, the silent drama wrecked, for, taking up the challenge, our artillery renewed its articulation. I was once more back in the Great War.

I saw terrible sights subsequently, endured cruel hardships. I saw the bones of snipers hanging freakishly from ruined trees, headless bodies, bodyless heads, a pair of soldiers, one British, one German, who had each bayoneted the other, standing, dead, and other gruesome things.

But the experience that stands out most vividly in my memory is that of the night when I sat in a tunnel near a Tyneside Scottish corpse, and the miraculous dawn of the following day.

B. Neyland served from September 1916 to December 1919: Sapper, Royal Engineers (Signals), Wireless Section. In France, January to June 1917, all this time in the Arras district. As wireless operator, took part in several attacks, wounded by shell splinter and home to Blighty, June 1917. On recovery sent to Ireland to help in the erection and maintenance of an almost unused wireless (military) service.

First published in Everyman at War (1930), edited by C. B. Purdom.

Photographs courtesy of Photos of the Great War website.

An "incendiary shell" is an artillery shell packed with highly flammable material, such as magnesium and phosphorous, intended to start and spread fire when detonated.

- Did you know?