Memoirs & Diaries - A Highland Battalion at Loos

For a whole week before the

Battle of Loos, the artillery of our Division were bombarding the German

trenches night and day, smashing up the barbed wire. On September

24th, 1915, my battalion, a Highland one, was moved up into covered-in

trenches ready to attack on the morning of the 25th.

For a whole week before the

Battle of Loos, the artillery of our Division were bombarding the German

trenches night and day, smashing up the barbed wire. On September

24th, 1915, my battalion, a Highland one, was moved up into covered-in

trenches ready to attack on the morning of the 25th.

At 3 a.m. we marched up the communication trenches under a heavy shell-fire from the enemy guns. Nearing the front line, we began to step over dead and wounded, and knew that it was no picnic, and that some of us would never return.

Arriving at the trench, it was over the top and the best of luck. Then we got our first taste of the real thing. Men of different battalions were lying about in hundreds, some blown to pieces lying mangled in shell holes. The platoon I belonged to arrived at a German trench, where about nineteen to twenty Jerries were shouting for mercy, after pinking some of us as we came forward. Someone shouted "Remember the Lusitania!" and it was all over with Jerry.

We moved on towards the village of Loos, where machine guns were raking the streets and bayonet-fighting was going on in full swing. Prisoners were being marshalled in batches to be sent under guard down the line. The most of the houses were blown in, but their cellars were strongly built and it was in these cellars that many Germans were hiding.

Two other sergeants and myself ran down into a cellar. To our surprise we found an old fellow in a white jacket, apparently an officers' cook. The table was laid with plenty of eatables and wines. The officers had a pressing engagement elsewhere. As we were feeling rather hungry, and to guard against being poisoned, we forced the cook to eat and drink first, and then we all had a good tuck in and felt the better for it; and took old Jerry upstairs a prisoner.

Leaving the cellar, I kept well into the side of the street to escape the flying metal, and came to a little estaminet. By the noise going on inside I thought they were killing pigs. I went inside and opened a door where blood was running out from underneath. It was certainly a pig-sticking exhibition. I saw some Highlanders busy having it out with Jerry with the bayonet. My assistance was not required, so I set off for Hill 70, our objective.

Through some misunderstanding about 500 of us went straight ahead towards Lens and passed a German redoubt, where they were all holding up their hands in surrender, but, as things were going well at the time we did not bother with them, as we were sure they were our prisoners, and we could take them any time.

Making our way through gaps in the German barbed wire, we got into the outskirts of Lens, but were held up by machine gun and rifle-fire and had to lie down and take cover, and try and dig ourselves in with our entrenching tools, which is not an easy job when you are lying flat. The ground was soft and muddy with the rain and seemed to have been a cornfield trampled well down.

The soldier lying next me

gave a Shout, saying, " My God! I'm done for". His mate next him asked

where he was shot. I did not catch what was said, but he drew himself

back and lifted his wounded pal's kilt, then gave a laugh, saying, " Jock,

ye'll no dee. Yer only shot through the fleshy part of the leg."

The soldier lying next me

gave a Shout, saying, " My God! I'm done for". His mate next him asked

where he was shot. I did not catch what was said, but he drew himself

back and lifted his wounded pal's kilt, then gave a laugh, saying, " Jock,

ye'll no dee. Yer only shot through the fleshy part of the leg."

Suddenly we got the order to retire and then saw the Germans sending forward strong reinforcements, and it is a wonder that any of us had the luck to get back, as the bullets were cutting the grass at our feet and flying round our heads like the sound of bees. I made for the gap in the wire I came through and found it piled with dead.

However, I made a jump and landed on top and rolled over on the other side. I felt something hot pass my neck. Putting my hand up I found no blood; the bullet had cut the neck of my tunic - a near thing.

But worse was to come. When we again faced the redoubt on the return journey, the Jerries were working their machine guns on us, knocking us down like nine-pins - a lesson never to leave prisoners behind with arms and ammunition. Only about fifty returned out of the 500 that advanced too far over the hill. I got back to the hill, and there got a chance to get my breath again. After midnight, our Division was withdrawn gradually, to allow another to take its place.

Our battalion was taken to a little village not far behind the line. There we had breakfast and a wash-up, and expected that we were going further back for a rest and reinforcements, as our strength was down to about 160. But our hopes were dashed, as the Division (what was left) was ordered back to the trenches that night, as things were not going too well on the hill. We held the trenches until the next morning when the Guards arrived and helped to put things in a stronger position.

The following day our pipe band met us at Mazingarbe and played us down to Noeux-les-Mines, where we went into billets, and had quite a nice time visiting estaminets, eating pomme-de-terres et oeufs, and speaking broken French.

Two or three days later we were entrained for Lillers, and there received our reinforcements. The new arrivals were eager to get up to the fighting line. They had their wish, for in less than a week we were back again for a spell of four days in a front-line trench beyond the village of Loos.

Before we got there we had

to march up a communication trench half full of water and mud for a couple

of miles, and looked like a lot of sewer rats when we reached the front

trench, which had belonged to the Germans.

Before we got there we had

to march up a communication trench half full of water and mud for a couple

of miles, and looked like a lot of sewer rats when we reached the front

trench, which had belonged to the Germans.

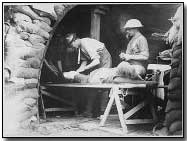

Then started the hard work cleaning up the muck and water, filling sand-bags and building up parts that had been blown in, and making snipers' posts, and all the time trench mortars were hurling over their shells, causing more muck and casualties.

Being the C.S.M. of my company, my duty was to take over trench stores, post guards, and detail ration parties to go down and meet the Q.M.S. at night, bring up the bully beef and biscuits and the most important of all, the rum. The men always got their tot about 4 a.m., and I can assure you they needed it. Standing about day and night wet and half-frozen, it always put new life into them.

Drinking-water was sometimes very difficult to get, and we had to bring it up in petrol tins. One day the water did not arrive. An officer's servant came to me and asked if he could get some to make the officer's tea. The only water, I told him, was that gathered in a waterproof sheet which was stretched above our heads in the dug-out to keep us dry. It was the colour of stout, and I was not very sure whether there were any dead Germans buried above us or not.

"Never mind; it will do fine. The officers will never know, as I will put plenty of tinned milk and sugar in it," and off he went with his kettle filled. The following night he brought me a small mug of hot tea which I enjoyed very much, but suddenly I remembered the water had not arrived, and asked where he got it. "Oh! just out of your sheet." I flung the mug at his head and chased him along the trench.

One night I detailed a party of bombers to hold a sap. Later on I took a turn up the sap to see if all was well and found every man knocked out by a shell. Another lot had to be detailed at once, and a burial party to take the dead away and have them buried before daylight. This was our usual daily occurrence.

Early

in the morning the snipers were at their posts, with telescopic rifles ready

to put a bullet into any German that happened to look over the top.

Early

in the morning the snipers were at their posts, with telescopic rifles ready

to put a bullet into any German that happened to look over the top.

One morning I stood beside Sniper McDonald, and watched the enemy lines through my periscope. Suddenly opposite us a box periscope went up and, after a survey of our lines, was taken down and put up again further along.

I told Mac to put it out of action next time. But instead of the periscope a Staff officer put his head up and looked around. I heard the ping of the sniper's rifle and saw Herr Von throw up his hands and fall back into his trench. Immediately another officer sprang up and shook his fist. Another ping and that was two he bagged that morning.

I am sorry to say that sniper was killed by a shell a week later. He was sitting with me and two or three others in a cover-in, down a support trench, when a shell hit the rear of our shack, nearly smothering us with muck. He darted to the opposite side to another shelter and the second shell, following hard on the first, got him.

One night in the front line the men were sitting about the fire-trench or wading about in the water, which was up to their knees, trying to keep themselves warm. It had been sleet and snow all day, and we had another two days to go before being relieved. I was walking along in the dark when I plumped into a hole full of water up to the hips.

Some of the boys had dug it during the day to give them a drier place to stand on. I had just managed to pull myself out, when I heard a splashing and someone running towards me, shouting, "Stand to, men! And, Sergeant-Major, come quick. The enemy are advancing in thousands on the right." I immediately ran towards the direction the noise was coming from, and found it was a young officer running about with a revolver in his hand.

How

he expected me to stop them I don't know. The men got up at once on

the fire-step, getting their rifles ready and blowing on their hands.

How

he expected me to stop them I don't know. The men got up at once on

the fire-step, getting their rifles ready and blowing on their hands.

The officer still kept shouting to me for God's sake to come quick. I thought it was funny, if an attack was on, that the Germans still kept throwing up their Verey lights.

I looked over the top and could see nothing. Neither could the sentries. The Captain came on the scene, gave him a telling off and ordered him back to his platoon, and passed the word along for the men to stand down. I think the young officer had got a touch of the "jumps", as it was his first spell in the front line.

C.S.M. Thomas McCall joined up at Inverness, September 1914, in the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders. After training at Inverness, Aldershot, and Salisbury, sailed for Prance, July 4th, 1915, with 44th Highland Brigade, 15th Scottish Division, and was with them at Loos, Somme, Arras, and the Belgian Front. Held the rank of company sergeant-major from September 27th, 1915, until the end of the war. Was fortunate in never being wounded, or on the sick list, though he had many narrow escapes. Left France December 11th, 1918, and was demobilized January 11th, 1919.

First published in Everyman at War (1930), edited by C. B. Purdom.

Photographs courtesy of Photos of the Great War website.

"Boche" was a disparaging term used to describe anything German.

- Did you know?