Memoirs & Diaries - An Old Contemptible at Le Cateau

On August 5th, 1914, I

reported to my regimental depot, being an Army Reservist. What a

meeting of old friends!

On August 5th, 1914, I

reported to my regimental depot, being an Army Reservist. What a

meeting of old friends!

All were eager to take part in the great scrap which every pre-war soldier had expected. At the depot all was bustle, but no confusion. In the mobilization stores, every reservist's arms and clothing were ticketed, and these were soon issued, with webbing equipment.

About 300 men were then selected and warned to hold themselves in readiness to proceed to the South Coast to make up the war strength of the battalion stationed there. There was great competition to go with this draft, the writer being one of the lucky ones to be selected.

We entrained next morning. Then another meeting with old chums. That night, bully, biscuits, emergency rations, and ammunition, were issued. Surplus kit was handed in and next night the battalion entrained for an unknown destination.

We eventually arrived in Yorkshire, and, after a fortnight's strenuous training, left for the South of England again, to join our division. By this time we had welded together, and were a really fine body of men, hard as nails, average age about twenty-five, and every man with the idea that he was equal to three Germans! Splendid men, enthusiastic, and brave, going to fight, they thought, for a righteous cause.

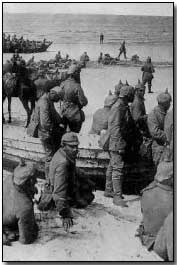

We embarked for France and landed at Boulogne on the morning of August 23rd. What a contrast between us and the slip-shod undersized French territorials who were guarding the docks!

In their baggy red trousers and long blue coats, they looked like comic-opera soldiers. We looked smart in our new khaki, and training had made us broad-chested and clean-looking. We disembarked and marched through the narrow streets of Boulogne singing popular songs.

The enthusiasm of the French people was unbounded. They broke our ranks to shower gifts upon us, and many a blushing Tommy was kissed by men and women. A few hours in camp, where we had to be guarded by gendarmes to save us from excited female admirers, and we entrained, leaving buttons and badges behind as souvenirs.

A tedious journey in horse trucks followed. The line was littered with empty bully tins and Woodbine packets, showing that British troops had passed that way before.

We detrained just outside Le Cateau station. The town was in confusion, as Mons had just been fought; refugees, troops, and ammunition columns creating a dust that choked us. Civilians offered us foaming jugs of weak beer, but discipline was so strong that to accept it meant a court martial.

We marched out of the town

along a typical French road. Just when we were about all in, a halt

was called for dinner, which we never had as an outburst of artillery fire

was heard.

We marched out of the town

along a typical French road. Just when we were about all in, a halt

was called for dinner, which we never had as an outburst of artillery fire

was heard.

It must have been miles away, but we had orders to open out to artillery formation and proceed: We saw no enemy that day, and at night bivouacked in a cornfield, where we enjoyed a long-delayed dinner.

We marched off in column of fours next morning at dawn in a new direction. At noon we halted, piled arms, and rations were issued-the last for many days. Men were told off to dig trenches on rising ground to our left.

Whilst so engaged an aeroplane hovered over us. It had no distinguishing mark, and we thought it was French, but were soon disillusioned, as it scattered coloured lights over us. Too late, we opened fire. Soon large black shells were bursting in the beet field just in front of our improvised position.

Rain then started, the shelling ceased, and a regiment of our cavalry came galloping up and jumped over us in our hastily constructed trench. We stayed there till nightfall, incidentally wiping out a small Uhlan patrol that blundered upon us.

When we withdrew we could hear the jingle of accoutrements of many men approaching. That night we seemed to march round and round a burning farmhouse.

Day broke, and we were still dragging our weary limbs along in what seemed to us to be an everlasting circle. At last the word came to halt and fall out for a couple of hours' rest. We had been marching along a road with a high ridge on the right and cornfields on the left. High up the ridge ran a road parallel to ours, on which one of our regiments had been keeping pace with us.

We had no sooner sunk down in the cornfield on our left than shrapnel began to burst over us. Our officers were fine leaders. "Man the ditch on the road," came the order.

In the meantime the battalion on the ridge had been caught napping by a squadron of Uhlans, who charged them while they were falling out for a rest. Our eager young officers went frantic with excitement. On their own initiative they led us up the hill to the rescue of our comrades. With wild shouts we dashed up.

At first the ground was

broken and afforded cover for our short sharp dashes. We then came to

a hedge with a gap about four yards wide.

At first the ground was

broken and afforded cover for our short sharp dashes. We then came to

a hedge with a gap about four yards wide.

A dozen youngsters made for the gap, unheeding the advice of older soldiers to break through the hedge. Soon that gap was a heap of dead and dying as a machine gun was trained on it.

We reached an open field, where we were met with a hail of shrapnel. Officers were picked off by snipers. A subaltern rallied us and gave the order to fix bayonets. A piece of shrapnel carried half his jaw away. Upwards we went, but not a sign of a German. They had hidden themselves and waited for our mad rush.

Officers and sergeants being wiped out and not knowing where the enemy really were, our attack fizzled out. A Staff officer came galloping amongst us, mounted on a big black charger. He bore a charmed life. He shouted something unintelligible, which someone said was the order to retire.

The survivors walked slowly down, puzzled and baffled. They had attained nothing, and had not even seen the men they set out to help. We lost half the battalion in that wild attack.

Then came our turn to do something better. The survivors, under the direction of a capable major, dug in and waited to get their own back. A battery of our eighteen-pounders started to shell the ridge. Suddenly shells started falling round the guns. One direct hit and a gunner's leg fell amongst us.

The battery was wiped out. Tired and worn out, we waited. Towards afternoon shrapnel played on us, fortunately without serious result. Then it was our turn to laugh.

German infantry were advancing in close formation. They broke at our first volley. Something seemed to sting my leg. I found a shrapnel bullet had ploughed a shallow groove down the fleshy part of my thigh. The enemy advanced. Another volley and they broke again. My leg began to pain me, so I hobbled along the road to a house which was being used as a dressing station.

A long queue of wounded men

were waiting to be dressed, whilst a crowd of thirst-maddened unwounded were

crowding round a well in the garden. Despairing of medical aid, I

begged a field dressing, and, catching sight of a sunken road, turned into

it, and dressed my wound.

A long queue of wounded men

were waiting to be dressed, whilst a crowd of thirst-maddened unwounded were

crowding round a well in the garden. Despairing of medical aid, I

begged a field dressing, and, catching sight of a sunken road, turned into

it, and dressed my wound.

In this sunken road, I found battalion headquarters. At dusk they retired, I with them. I learnt afterwards that all our wounded were captured that night, and small bodies of our troops, trying to retire in the darkness, had fired on each other. This was our part in the Battle of Le Cateau.

Then began the retreat. I must have fainted, for I remember hobbling along with some chums, and next I found myself tied to the seat of an ammunition limber. We came to a village jammed with retiring troops, where an artillery officer bundled me off. Fortunately some of my own regiment passed, and, seeing me lying in the road, helped me along.

My leg seemed easier and I was able to proceed at the pace my footsore companions were going. It was nightmare marching. Our party was now about 150 strong. Sleep was out of the question, and food was begged from villagers.

Reaching St. Quentin, we had great hopes of rest, but were told that we were surrounded. We lay down to die through sheer weariness, but a Staff officer rounded us up, and got us out just as the enemy entered. Tramp, tramp, again.

Engineers told us to hurry over the bridge at Ham, as they were just about to blow it up. A little scrap a bit further on, then Noyon, where we snatched a night's sleep.

One day we turned about; other parties joined us, and we were told we were now advancing. We hardly believed it until we came upon dead Germans. That put new life in us. Advancing! Hurrah!

Our part was very small up to the Aisne. We crossed the Marne without a scrap, and never met with opposition until we reached the heights the other side of that now famous river.

Some of our brigade were

not so fortunate, and lost heavily from shell-fire while crossing. Our

position on the Aisne was not so bad.

Some of our brigade were

not so fortunate, and lost heavily from shell-fire while crossing. Our

position on the Aisne was not so bad.

We dug in on top of the ridge beyond the river. We were 1,100 yards from the enemy; and every four days we retired to a vast, evil-smelling cave, where we got hot meals and remained for two days.

Most of our casualties were caused when fetching water and rations from the village below.

The battalion was made up with reserve men and the weather continued fine. The trenches on our left were not so fortunate, as they were attacked nearly every night, this causing us to stand to all night. After a few weeks of this we were relieved by French troops.

By forced marches and a train journey, we reached St. Omer. One night there, and we boarded French motorvans. We soon found ourselves scrapping after we had disembarked at a small village.

The enemy had dashed down and seized the next village, Meteren, and our first task was to drive them out. The place was held by a rearguard of machine-gunners, and could have been encircled and captured, but we were ordered to take it by bayonet.

We took it at a terrible cost, but found no enemy to bayonet. What few machine-gunners were there had done their work well and fled in time. Then through Bailleul and Armentieres, which the enemy abandoned without a fight.

We were the first British troops in Armentieres. As we marched through, the civilians went frantic with delight. The Germans had been there for a week, and had committed the usual excesses of troops flushed with victory. The Highlanders in our brigade caused much amusement, the female part of the population shrieking with laughter at the dress of the "Mademoiselle Soldats".

Bread, beer, and tobacco were showered on us, and garlands of flowers hung on our necks and bayonets. However, a few hours only were our portion there, which we spent in a large flax factory wrecked by the enemy during their short stay.

Off

again past a large lunatic asylum, on which shells were falling, the shrieks

of the inmates sounding hideous.

Off

again past a large lunatic asylum, on which shells were falling, the shrieks

of the inmates sounding hideous.

These poor devils were released, and some wandered into the firing line, and no doubt thought they had reached the infernal regions.

The enemy took up a strong position at Houplines, where, after several minor attacks to straighten the line, we dug in, and then commenced the dreary trench warfare.

I have not enlarged on the hardships of war up to now, as, being all healthy men and constantly on the move, we had not noticed them much. Settling down to inactive trench life, we soon discovered what a miserable state we were in.

Most of the original men had left their spare kit and overcoats at Le Cateau, as we had received orders there to attack in fighting kit. We were in the front line at Houplines twenty-nine days at one stretch. I for one had neither shirt nor overcoat. My shirt had been discarded at the Aisne, being alive with vermin.

Beards were common, and our toilet generally consisted of rubbing our beards to clear them of dried mud. Our trenches were generally enlarged dry ditches, where we dug in when our advance was stopped. Sandbags were very scarce, and when it rained the sides of the ditches fell in. However, at Houplines we were better off than the majority of British troops at that time.

It was a fairly quiet position and rations came up regularly and plentifully. Fetching rations was our worst job, as the enemy's powerful searchlights played along the roads leading to the trenches each night. There were always plenty of volunteers, however, for this job, as they had first go at the rum, cigarettes, etc.

At the back of our trench was a large farmhouse. It had been shelled to pieces, but it proved a Godsend to us, as we discovered the wine cellar intact. Dozens of bottles of good wine were conveyed to the trench. The one officer in the trench (not popular enough to be told of our find) must have been struck with the cheery light-heartedness of the men at this period.

We were at last relieved

and proceeded to a large brewery at Nieppe, where four days' rest, a bath,

and clean underclothing made new men of us.

We were at last relieved

and proceeded to a large brewery at Nieppe, where four days' rest, a bath,

and clean underclothing made new men of us.

This was our first good wash since leaving England. I had not worn a shirt for six weeks. Whilst bathing (in large mash tubs), our khaki was fumigated. This seemed to send the lice to sleep for a couple of days, then they woke up and attacked with renewed vigour.

A draft of returned wounded men joined us and we left Nieppe to take up a position in front of Ploegsteert Wood. We spent the winter there doing good work, barbed wiring, and strengthening the position. The First Battle of Ypres was raging on our left. Four days front line, four reserve, and four in billets, until in April 1915 we were pitched into that awful hell, Ypres, when the battalion was wiped out time after time.

I lasted until Arras 1917, the only real victory I saw, when I received a longed-for Blighty one and got discharged.

Private R. G. Hill. Went to France on August 22nd, 1914, with the 1st Battalion Royal Warwickshire Regt., in the 10th Brigade of the 4th Division. Except for a few days in hospital in 1915, served with this battalion until April 11th, 1917, when he was wounded in the face, and was discharged medically unfit in March 1918. In Action at Le Cateau, Marne, Aisne, Meteren (a little-known, but gallant fight), Armentieres, Ploegsteert, Ypres (1915), the Somme, and Arras (1917).

First published in Everyman at War (1930), edited by C. B. Purdom.

Photographs courtesy of Photos of the Great War website.

A "conchie" was slang used to refer to a conscientious objector.

- Did you know?