Feature Articles - Magical Slang: Ritual, Language and Trench Slang of the Western Front

Unprecedented in its conditions, ferocity, and slaughter,

the First World War was also unprecedented in its effect on the psyches of

the men who fought and on the languages they spoke. Like the soldiers

who spoke it, English emerged from the war, as Samuel Hynes maintains, a

"damaged" language, "shorn of its high-rhetorical top..." (1)

Unprecedented in its conditions, ferocity, and slaughter,

the First World War was also unprecedented in its effect on the psyches of

the men who fought and on the languages they spoke. Like the soldiers

who spoke it, English emerged from the war, as Samuel Hynes maintains, a

"damaged" language, "shorn of its high-rhetorical top..." (1)

French linguistic purists, led by the Academie Francaise, vigorously denounced damaging incursions of journalistic language and trench slang into standard French. (2) Only in Germany did a nationalist ideology with its high rhetoric of struggle, sacrifice, and military glory survive, adopted and nourished first by rightist veterans' groups and paramilitary formations, and finally institutionalised by the National Socialists and their leader, former Frontsoldat Adolf Hitler.

But whatever damage the war may have wrought on the "high" language is, in a sense, compensated by the emergence of two new popular "languages" of great interest to the historian. One is the language of popular journalism; already well-established in 1914, it was characterised by its own chauvinistic diction and aggressively patriotic attitude and was the means by which most civilians got information about the war.

Universally excoriated by the fighting troops as bourrage de crone (head stuffing, i.e. false stories) and Hurrah-patriotismus (hurrah patriotism), journalistic prose nevertheless significantly shaped civilian attitudes about the war and soldiers' attitudes about the press. (3) French troops called the official war bulletin le petit menteur (the little liar). The other language was, of course, what we call trench slang, the common idiom of the front. The literate mass armies trapped in the entrenched stalemate of the First World War provided a fertile medium for the development and dissemination of the special language of the trenches. (4)

In this essay, I intend to focus on the two predominant roles of slang in the context of the Western Front: its denotation of membership in the community of combat soldiers, and its magical or talismanic function as the protective language of that community and its individual members. The selected examples are meant to be illustrative rather than exhaustive.

Among

the many rhetorical and social functions of slang and jargon, that of

defining and delimiting a social group by reinforcing its social,

professional and often visual identity with a verbal one is broadly

significant. (5)

Among

the many rhetorical and social functions of slang and jargon, that of

defining and delimiting a social group by reinforcing its social,

professional and often visual identity with a verbal one is broadly

significant. (5)

Robert Chapman has noted that "an individual... resorts to slang as a means of attesting membership in the group and of dividing himself... off from the mainstream culture." (6)

Niceforo neatly pinpoints the genesis of slang: "sentir differement, c'est parler diffJrement; - s'occuper differement, c'est aussi parler differement" ("to feel differently is to speak differently; - to occupy oneself differently is also to speak differently"). (7) The creation of a verbal identity based on occupation and feeling is particularly marked in military society, where social function, enforced separation from the civilian world, and uniform appearance already distinguish the members of a circumscribed, hierarchical society from outsiders.

It would be useful at this point to differentiate between the terms "jargon" and "slang" in a military context, as both exist, are sometimes commingled, and often confused. (8) By jargon I mean the language of the profession, consisting primarily of technical terms (including acronyms) proper to the military service, what Flexner calls "shop-talk." (9) In current American military jargon, for example, the acronym PCS, which stands for Permanent Change of Station, appears occasionally as a noun, as in "Did you have a good PCS?" but more frequently as a verbal structure, as in "He PCSed last month" or "She's PCSing in January."

The "alphabet soup" of acronyms, an enduring characteristic of military jargon, first appeared in bewildering array in the First World War, although some had existed earlier. (10) Military jargon is, of course, not limited to acronyms, but includes such things as abbreviations for weapons and equipment, terms for promotion and failure, punishments under the code and the like.

Genuine slang, on the other hand, generally eschews technical terms in favour of the renaming of objects and actions, and the invention of neologisms. Chapman remarks that slang relies heavily on "figurative idiom... (and) inventive and poetic terms, especially metaphors." (11) Partridge likewise signals the importance of metaphor and figurative language of all sorts. (12)

Drawing again on current American usage, the gold oak leaves on a field-grade army officer's hat become "scrambled eggs" and the collective designation for senior officers is "brass hats" or simply "the brass," a phrase which, along with many others from the two world wars, has migrated into the general vocabulary. (13)

The hats of field-grade air force officers are decorated with stylised clouds and bolts of lightning, universally dubbed "darts and farts." Similarly a colonel, who wears eagles as his insignia, is distinguished from a lieutenant colonel by being called an "eagle-colonel," or with the fine pejorative edge present in "scrambled eggs" and "darts and farts," a "chicken colonel." To the disparagement implicit in such phrases, I shall shortly return.

The military proclivity for acronyms occasionally and amusingly spills over into true slang. A famous instance is that Second World War favourite "SNAFU," politely rendered as "situation normal, all fouled up." A rudimentary knowledge of scatological language will quickly provide the ruder and more popular version. (14)

In

wartime, the general store of military slang is augmented by a special

subspecies - the slang of combat troops.

In

wartime, the general store of military slang is augmented by a special

subspecies - the slang of combat troops.

Such troops use the general slang but employ, in addition, a vocabulary unique to their situation. The slang of combat troops distances its users from the safe, punctilious (and by implication, cowardly) rear echelons, while concomitantly reinforcing the separate identity and moral superiority of the combat units. (15)

Anyone familiar with the literature of World War I will immediately recall the pervasive "us vs. them" mentality of front and rear and the suffocating smugness of staff officers. The front line troops psychologically and linguistically occupied the moral high ground of courage, suffering and sacrifice, leaving the rear to hold the low ground of shirking and blind adherence to form and tradition at the cost of lives. Franz Schauwecker wrote that there was a crack in the structure of the army that "ran parallel to the front somewhere just outside the range of enemy fire." (16)

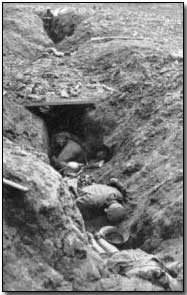

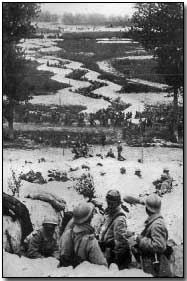

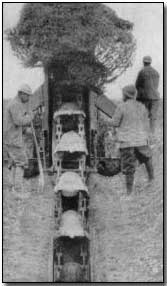

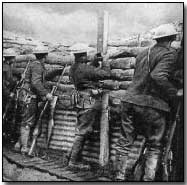

Before examining the characteristic language of the trench soldiers of World War I, let us briefly review the physical and psychological stresses inherent in the static trench systems of the Western Front, and the ways in which the troops coped with those pressures. In the forty years of European peace that followed the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, the general staffs of the armies analysed the campaigns, drew their conclusions, and plotted their strategies for the rematch that most were convinced was inevitable.

Unlikely as it may seem, the generals of victorious Germany and defeated France arrived at the same conclusions: only total offensive - offensive B l'outrance - could ensure victory. While the Germans planned the von Schlieffen offensive, Revanche became the motive force behind French military planning in the years between the wars. (17)

With all sides (including the British, despite their experience in the Boer War) committed to the theory of the offensive, the sudden concretion of the long-awaited war into defensive entrenchment baffled even the generals. In their obsession with the offensive, and with its psychological component of troop morale, they had failed to recognise that the enormous technological advances in weaponry worked more to the benefit of defence than of offence. The Western Front was shaped by artillery, the machine gun, barbed wire, and the spade. As early as October of 1914, a prescient young German officer wrote to a friend that

(t)he brisk, merry war to which we have all looked

forward for years has taken an unforeseen turn.

Troops are murdered with machines, horses have

almost become superfluous... The most important

people are the engineers... the theories of decades

are shown to be worthless. (18)

Unfortunately for the miserable troops mired in the wet,

cold, and filthy trenches, the generals refused to accept the deadly

efficacy of the defensive weapons, and spent the first three years of the

war mounting one costly frontal assault after another, until the abortive

Nivelle offensive of May 1917 precipitated the mutiny of the French army and

ended what J.M. Winter calls "the great slaughter." (19)

Unfortunately for the miserable troops mired in the wet,

cold, and filthy trenches, the generals refused to accept the deadly

efficacy of the defensive weapons, and spent the first three years of the

war mounting one costly frontal assault after another, until the abortive

Nivelle offensive of May 1917 precipitated the mutiny of the French army and

ended what J.M. Winter calls "the great slaughter." (19)

What, then, was the effect of trench warfare on the soldiers? First, the experience of war was an initiatory one. That is, the experience is, per se, so remarkable that no one who has not experienced it can ever share it or understand it. (20)

For Aldington soldiers were "men segregated from the world in this immense barbaric tumult." (21) "Ein Geschlecht wie das unsere ist noch nie in die Arena der Erde geschritten," ("A generation such as ours has never before stepped into the arena of the earth") proclaimed Ernst Junger. (22)

This "initiate mentality" among combat troops was immeasurably strengthened in World War I by the characteristics of the fighting, the first of which was a tactical stasis that imposed physical inertia on the front line troops. The soldiers were literally immobilised in a maze of trenches, subjected to severe shelling and regular sniping, to say nothing of the rigours of outdoor life in northern Europe, with virtually no reliable protection from any of them. It is little wonder that the most common metaphor for the trench system, and by extension the war itself, was the labyrinth, a true "initiatory underground." (23)

It was not lost on German troops that the root word of der Schhtzengraben (trench) was das Grab, a grave. In Otto Dix's lost painting, Der Schhtzengraben, the trench becomes a grotesque grave filled with horribly mutilated bodies.

The group identity of the "troglodytes" (to borrow Fussell's term) emerges in the striking special language of trench slang. In his preface to Dechelette's dictionary, Georges Lentre recounts hearing a conversation between two soldiers that appeared to be mutually intelligible, but which he found incomprehensible. (24)

Against the incomprehension of the rear and the patriotic drivel of the press, the troops erected a linguistic wall that Jacques Meyer perceptively calls "le language d'une franc-mahonnerie" ("a language of free-masons"). (25)

The sense of identity and community is evident in what the soldiers called themselves. The usual two-week stint in the front and reserve lines tended to leave soldiers filthy, lousy, unshaven, and exhausted. (26) For the Germans, a front line infantryman was a Frontschwein, a front pig. For the French, he was a poilu, literally a hairy beast, as the noun poil is used primarily for the hair of animals. Dauzat points out that the term implies more than just an unshaven man, because the poilu is hairy, as he delicately puts it, "au bon endroit," - a traditional symbol of virility. (27)

In neither case is the animal reference pejorative. Bill Mauldin's World War II cartoons of "GI Joe" stand in the same tradition of affectionate commonality, all contempt reserved for those who are not a part of the community of combat.

The

sense of community felt by the combat troops (a bond particularly marked

among the Germans) was reinforced by the mass of war material thrown against

them.

The

sense of community felt by the combat troops (a bond particularly marked

among the Germans) was reinforced by the mass of war material thrown against

them.

The Germans, in fact, use the phrase "war of material" (Materialschlacht) instead of "war of attrition" for the 1916-1918 period.

Front line soldiers often felt that they had more in common with the enemy soldiers in the trenches opposite than with their own rear echelon troops and the people at home. That sense of a common bond of suffering is reflected in the slang names for opposing and even allied forces. With the exception of boche, and perhaps "Hun," to which I shall return, epithets for opposing forces were generally based on a stereotypical national name or characteristic or a deformed foreign phrase, and were largely inoffensive.

On the German side, the favoured names for the French were Franzmann and several names based on germanised French phrases: Parlewuhs (parlez-vous), Wulewuhs (voulez-vous), Olala, and the very popular Tulemong (tous le monde). (28) For British soldiers, the Germans, like the French, used "Tommy," although naturally deforming the pronunciation.

English soldiers employed a variety of epithets for the Germans. "Fritz" was popular early in the war, with "Jerry" favoured later. According to Brophy, "Hun," a journalistic creation, was used almost exclusively by officers, as was the borrowed French "Boche."

Although the French used Fritz as well, Boche was the term of choice. Its etymology is complex and uncertain, (29) but its pejorative implications of obstinacy and generally uncivilised behaviour are undeniable. The Germans loathed the word and considered it a profound insult. Bergmann claimed that the Germans used no such derogatory terms, for "wir Deutschen wissen uns zum Glhck frei von... kindischen Hass" ("we Germans know ourselves to be happily free from such childish hatred"), but Dauzat disputes that. (30)

The unusually derogatory nature of Boche may reflect French bitterness over the defeat of 1870 and the invasion of 1914. Dauzat insists that Boche is a "mot de l'arripre" ("a word of the rear"), and that the soldiers preferred Fritz, Pointu (for the pre-1916 German spiked helmets) or even Michel for artillerymen. (31) Nevertheless, the other collective epithets suggest, in their general mildness, that the front line troops considered enemy soldiers less dangerous than the men to their rear.

Entrapment, immobility, and alienation led to what Leed has called "the breakdown of the offensive personality." (32) Instead of being a mobile offensive warrior, the soldier of trench warfare was "humble, patient, enduring, an individual whose purpose was to survive a war that was a 'dreadful resignation, a renunciation, a humiliation.'" (33)

A young German soldier, Johannes Philippson, wrote home in the summer of 1917 that "only genuine self-command is any use to me." (34) French historian Marc Bloch described the feelings of his troops in December 1914: "Trench warfare had become so slow, so dreary, so debilitating to body and soul that even the least brave among us wholeheartedly welcomed the prospect of an attack." (35)

How, then, could soldiers combat the soul-killing

existence in the trenches and the ever-present fear of death and wounds? One

method was through a reliance on talismans and rituals. As Fussell has

noted "no front-line soldier or officer was without his amulet and every

tunic pocket became a reliquary... so urgent was the need that no talisman

was too absurd." (36)

How, then, could soldiers combat the soul-killing

existence in the trenches and the ever-present fear of death and wounds? One

method was through a reliance on talismans and rituals. As Fussell has

noted "no front-line soldier or officer was without his amulet and every

tunic pocket became a reliquary... so urgent was the need that no talisman

was too absurd." (36)

Luck also depended on ritual - on doing some things and refraining from others, doing things in threes for example, or Graves' conviction that his survival was due to the preservation of his virginity. (37) Another form of talismanic protection was provided by the use of slang. Niceforo defines "magical slang" ("l'argot magique") as the language used by individuals when they fear (for reasons having a magical basis) to call things and people by their real names. (38)

Slang allowed the troops to create a ritualised discourse, fully intelligible only to the initiates, that suppressed fear by avoiding any mention by name of death, wounds, weapons, and the authorities whose orders could expose a soldier to those dangers. In short, the trench slang of World War I served a protective function by creating a language that familiarised, trivialised, and disparaged those objects and persons posing the greatest danger to the individual soldier.

One of the most important taboos in the language of soldiers was any mention of death. While the author of a novel or memoir may state in a narrative capacity that someone was killed or wounded, such statements are nearly non-existent in the dialogues of soldiers. Niceforo notes that the taboo against mentioning death is very widespread, even in modern cultures. (39)

The taboo is particularly strong when death is omnipresent. A "Tommy" might say "He's gone west" or "He's hopped it." The Germans simply said Er ist aus (He's gone, done for). (40) A poilu remarked that his comrade had earned la croix de bois, the wooden cross, probably an ironic formation on croix de guerre. The important decorations for valour on all sides in the First World War were in the shape of a cross, providing ample scope for metaphoric formations.

As an interesting comment on the insignificance of medals to common soldiers, German Frontsoldaten scathingly called all decorations Zinnwaren, (tinware), while the French referred to them as batterie de cuisine (cookware).

Wounds were handled in much the same way. British and German troops had similar expressions for desirable wounds, just serious enough to ensure that the wounded man would be evacuated home. For the British, such a wound was a "Blighty," a term derived from a Hindu word meaning a foreign country and taken up by British troops in India to refer to Britain.

For the Germans, it was a Heimatschuss (a home shot), or an Urlaubschuss (a leave shot), or even a Deutschlandschuss (a shot that gets one to Germany). For the French, who were already on home ground, une fineblessure, (the adjective weakens the gravity of the noun), nevertheless ensured evacuation and convalescence far from the front.

The tendency to familiarise and trivialise is most apparent in the names for weapons. In the age of the Materialschlacht, the terrifying killing and maiming power of high explosives posed the greatest threat to infantrymen on the Western Front, followed by rifle and machine-gun fire. The distant impersonality of the killing (one scarcely ever saw the enemy), and its unpredictability made it particularly threatening.

Trivializing names for weapons and their projectiles reduced the psychological sense of danger. Bergmann notes that the tradition of naming heavy guns reaches at least to the early seventeenth century. (41) The soldiers of the Great War, faced with the most destructive technology then known, were not behindhand. All the combatants referred to the various artillery weapons by their calibres. Everyone spoke of "75s," the French 75 millimetre field gun, and "180s," the German heavy howitzer.

German field guns of various calibres were variously

dubbed wilde Marie, dicke Marie, dicke Bertha (the famous "Big

Bertha"), der liebe Fritz, der lange Max, and schlanke Emma.

(42) The manoeuvrability of the French 75 was honoured in the name

Feldhase (field hare). The French called their 75 Julot,

which seems to have been one of the few French names in general circulation

for heavy artillery pieces.

German field guns of various calibres were variously

dubbed wilde Marie, dicke Marie, dicke Bertha (the famous "Big

Bertha"), der liebe Fritz, der lange Max, and schlanke Emma.

(42) The manoeuvrability of the French 75 was honoured in the name

Feldhase (field hare). The French called their 75 Julot,

which seems to have been one of the few French names in general circulation

for heavy artillery pieces.

The French trench mortar, a squat, blunt-nosed gun with angled supports, was called "le crapouillot," a word formed from "crapaud" (toad), either from its shape or the fact that its shells fired almost vertically and then dropped into the opposing trench line, much like the hop of a toad. Bergmann has correctly assessed the effect of naming guns for people (especially women) and animals: "...man sucht auch auf diesem Wege sich die unheimlichen Kriegsmaschinen n@her zu bringen, sie sich vertrauter zu machen und ihre Gefahr gleichsam geringer erscheinen zu lassen" ("in this way one seeks to bring the sinister war machines closer, to make them more familiar and, as it were, to let their danger appear slighter"). (43)

The British seem to have been disinclined to name their guns, but all three languages are richly furnished with names for the projectiles, probably because ordinary infantrymen tended to be on the receiving end. Because of the large quantity of black smoke produced by the explosion, a heavy shell was called a "Jack Johnson", or a "coal-box."

In French, a similar shell was un gros noir, and one that exploded with greenish smoke was un pernod, named after the popular drink. Others were saucissons (sausages), sacs B terre (sand bags) and marmites, named after the large, deep cooking pot of the same name. Germans called a heavy shell an Aschpott (ash pot) or a Marmeladeneimer (jam pot). The British trivialised the German mine thrower - the Minnenwerfer - by calling its whistling shells "singing Minnies," thus reducing a dangerous weapon to the status of a harmless girl. (44)

Similarly, the German hand grenades, which had handles, quickly became known as "potato mashers," which they did, indeed, resemble. The oval hand grenades of France and Britain were called les tortues (turtles) by the French and Ostereier (Easter eggs) by the Germans. A German discus-shaped hand grenade was a Nhrnberger Lebkuchen, the famous gingerbread Christmas cookie. In all of these cases, the movement is to trivialise and familiarise the weapons by noting a resemblance to something common, familiar, and above all, harmless.

The racial and sexual innuendo inherent in several of the slang names (i.e. Jack Johnson, Big Bertha) is part of the same pattern and reflects the attitudes of the period; it is not like the deliberately derogatory and ironic slang used for the rear echelons, as we shall see.

The front line troops also displayed the greatest inventiveness in their slang names for infantry weapons, colouring the euphemism with an ironic twist. Take, for example, the machine gun, the most dangerous infantry weapon. The Germans generally used the acronym MG for Maschinengewehr, although Stottertante (stuttering aunt) and Nuhmaschine (sewing machine) were current. (45) The British called their own machine guns Lewis guns and the enemy's Maxim guns, named for their inventors.

But for the poilu, the machine gun became un moulin B cafe - a coffee mill - first because the early gatling-gun types were hand-cranked, and secondly for the sound they made. In any event, the gun was reduced to being a familiar household object in everyday use. Later in the war irony took over, and the machine gun was also called la machine B decoudre - a machine to rip open seams, ironically formed on machine B coudre (sewing machine). The verb decoudre also denotes the action of a horned animal ripping open its attackers, giving the phrase a sinister undertone.

But the cleverest French slang involves the bayonet.

The French army had succumbed to a veritable cult of the bayonet in the

period before the war. It was regarded as the infantry weapon par

excellence, the embodiment of the offensive spirit, and the bayonet

charge as the surest indication of military elan among foot soldiers

- the infantry equivalent of a cavalry charge.

But the cleverest French slang involves the bayonet.

The French army had succumbed to a veritable cult of the bayonet in the

period before the war. It was regarded as the infantry weapon par

excellence, the embodiment of the offensive spirit, and the bayonet

charge as the surest indication of military elan among foot soldiers

- the infantry equivalent of a cavalry charge.

In the realities of trench combat, as Jean Norton Cru has shown, the bayonet, despite its sinister appearance and exalted reputation, was little used and produced minor wounds in comparison to the effects of shrapnel and bullets. (46)

But it was a favourite for nicknames, the most famous of which is Rosalie, from a 1914 song far more popular among civilians than among soldiers. (47) The bayonet was known as la fourchette (the fork), and le cure-dents (the toothpick), as well as a tire-Boche and a tourne-Boche. In the last cases Boche, as the general slang term for the Germans, is substituted into existing phrases.

The former comes from tire-bouchon, a corkscrew, possibly a reference to the twisting movement that soldiers were taught to use in a bayonet thrust. The latter, tourne-boche, is formed from tournebroche, a kitchen spit for roasting meat and fowl in the fireplace.

One of the most striking characteristics of slang is its inclination toward degradation rather than elevation, what Partridge following Carnoy has called dysphemism. (48) Niceforo calls it "l'esprit de degradation et de depreciation," ("the spirit of degradation and depreciation") and goes on to speak of slang as a form of assault directed at a higher class by an underclass. (49)

In its deliberate deformation of words, mispronunciation and taste for impropriety, slang may serve as the only act of rebellion allowed soldiers at war. While most mispronunciations of French place names were probably just that, a few are so wonderfully ironic that they must have been deliberate, such as the German deformation of Neufchatel to Neuschrapnell (new shrapnel). (50)

Fear, and the hatred it spawned, was directed above all toward the "powers that be," the perfidious and murderous ils (they) as Meyer calls them. (51)

The combat soldiers' hatred of the rear, which certainly involved some envy as well as a sense of moral superiority, rested also on a sense of betrayal - the certainty that the powers, civilian or military, that ordered their lives cared little for them. As we will see, slang terms for rear echelon troops in French and German abound in animal and vegetal metaphors, constituting a figurative vilification of intelligence, courage, and manhood.

The conviction that their lives were not valued emerges in numerous guises in the slang, including slang used for food, which was, naturally, a major preoccupation of troops who were often badly fed. The men exercised their traditional right to grumble about the food and create disparaging epithets to describe it, a custom going back to the "grognards" of the Napoleonic Wars and beyond, and certainly continuing to our own time.

One of the staple rations in World War I was British canned beef, called "Bully" beef by the troops. ("Bully" is probably a corruption of the French bouillie, boiled). The Germans also called it "Bully," and liked it so well that they rarely returned from a trench raid without some, especially since German rations worsened as the war lengthened and the allied blockade cut off German resources.

By 1916, the staple of the

German soldier's diet was a mixture of dried vegetables, mostly beans, that

the Frontsoldaten called Drahtverhau (barbed wire).

Other German culinary delights included Stroh und Lehm (straw and

mud - yellow peas with sauerkraut), and Schrapnellsuppe (shrapnel

soup - undercooked pea or bean soup).

By 1916, the staple of the

German soldier's diet was a mixture of dried vegetables, mostly beans, that

the Frontsoldaten called Drahtverhau (barbed wire).

Other German culinary delights included Stroh und Lehm (straw and

mud - yellow peas with sauerkraut), and Schrapnellsuppe (shrapnel

soup - undercooked pea or bean soup).

Jam, essential for softening stale bread, was Heldenbutter (hero's butter), Wagenschmiere (axle grease), and Kaiser-Wilhelm-Ged@chtnis-Schmiere (Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Spread). (52) Some of these terms may refer specifically to the notorious turnip jam that became standard issue after the blockade and crop failures created severe shortages. Spread on ersatz bread made with sawdust and other fillers, it was neither appetizing nor nourishing.

The French did not share their enemy's or ally's taste for "Bully". They referred to it as singe, (monkey), and boTte B grimaces, for the grimaces it produced. Other regular items in the French soldier's diet included schrapnells (undercooked peas or beans), and lentils, known as punaises (bugs).

They called a stew a rata, a shortened form of ratatouille, which in its general sense refers to a stew, not merely the vegetable stew which it designates in modern French. Rata however, also suggests the verb ratatiner (to shrivel or dry up), which may be a remark on the quality of army cooking.

The use of slang as insult, as defensive and offensive weapon, reached its peak in the front line soldier's contempt for rear echelon soldiers and for civilians. The universal distain for the staffs, soldiers and officers alike, in their relatively safe and sheltered jobs, surfaces in all three languages with vitriolic implications of cowardice, greed, and self-seeking.

In the British army, staff officers were distinguished by the wearing of bright red shoulder tabs and hat bands. The colour constituted a visible symbol that the wearer did not belong to the colourless khaki and field-grey world of the front, where distinguishing marks were abolished because they made good targets for snipers. The frontline troops soon dubbed the tabs "The Red Badge of Funk." (53) Along this line, one of the trench newspapers provided the following definition of "military terms":

DUDS - These are of two kinds. A shell on impact

failing to explode is called a dud. They are unhappily

not as plentiful as the other kind, which often draws a

big salary and explodes for no reason. These are

plentiful away from the fighting areas. (54)

The implication of cowardice is less obvious in the French and German terms for staff officers, but the scorn is deepened by the use of animal references. In the German Frontschwein, used for the front soldiers, Schwein was an expression of community and commonality, almost of endearment.

But the equivalent term for headquarters soldiers, Etappenschwein, was entirely pejorative. The German focus, understandably, since the German troops were very ill-fed, was greed. Rear echelon troops were often called Speck (bacon), and one writer even referred to the Etappenschweine as "bellies on legs." (55)

The French slang is inventively pejorative. For them, the headquarters sergeant was a chien de quartier, a headquarters dog. The choice of animal is significant, as chien is a broadly-used pejorative in French, common in such phrases as chien de temps (bad weather), chien de vie (a dog's life) and Ltre chien (to be stingy).

The term in widest use for someone who had a safe job was embusquJ, whose first meaning is someone lying in ambush. The word consequently carries connotations both of hiding and, worse, of betrayal.

Another term, planquJ, has the original meaning of lying flat, ie.

safely out of the line of fire; a similar term is assiettes plates

(flat plates). The most insulting epithet is the opposite of poilu,

JpilJ (someone who has been depilitated), implying the loss of the

vaunted courage and virility of the poilu.

Another term, planquJ, has the original meaning of lying flat, ie.

safely out of the line of fire; a similar term is assiettes plates

(flat plates). The most insulting epithet is the opposite of poilu,

JpilJ (someone who has been depilitated), implying the loss of the

vaunted courage and virility of the poilu.

High ranking officers, invariably staff officers, since the troops rarely saw anyone above the rank of captain, were reduced to lJgumes (vegetables) and generals to grosses lJgumes (big vegetables). A brigadier's stripes of rank were sardines, suggesting in French, as in English, a small, smelly fish.

In conclusion then, the unique conditions of the First World War (a war of defensive weapons led by generals obsessed with offensives) engendered a level of psychological stress in the combatants hitherto unknown in Europe. Along with talisman and ritual, the slang of the trenches provided a stylised discourse for the initiates of the labyrinth, through which they could define themselves as initiates, and simultaneously protect themselves from the constant awareness of their horrific situation.

As John Brophy has said of Great War soldiers' songs, the slang may not have diminished the soldier's danger, but it "may well have reduced the emotional distress caused by fear, and aided him, after the experience, to pick his uncertain way back to sanity again." (56)

Notes

1. Samuel Hynes, A War Imagined: The First World War and English

Culture (New York: Athenaeum, 1991) 353. See also Paul Fussell, The

Great War and Modern Memory (New York: Oxford UP, 1975) 2123.

2. FranHois DJchelette, L'argot des poilus (Paris: Jouve, 1918) 12.

3. See also Richard Aldington's bitter denunciation in Death of a Hero (London: Chatto, 1929) 293. A profound distrust of the press is one of the enduring legacies of the war. It is, however, more evident in Britain and France than in Germany, where the historic function of the press was significantly different. See Fussell, Great War 316, and Modris Eksteins, The Limits of Reason: The German Democratic Press and the Collapse of Weimar Democracy (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1975). Regrettably no systematic study of the "journalese" of war reporting exists. Scott D. Denham, Visions of War: Ideologies and Images of War in German Literature Before and After the Great War (Bern: Lang, 1992) traces the transformation of war reporting into war fiction.

4. The term is from Alberto Niceforo's classic study, Le gJnie de l'argot (Paris: Mercure de France, 1912). Trench slang quickly drew the attention of linguists. Particularly useful on French trench slang are DJchelette, cited above, Albert Dauzat, L'argot de la guerre (Paris: Colin, 1918), and Dictionnaire des termes militaires et de l'argot poilu (Paris: Larousse, 1916). On German, see Karl Bergmann, Wie der Feldgraue spricht: Scherz und Ernst in der neusten Soldatensprache (Giessen: T`pelmann, 1916), and Otto Mausser, Deutsche Soldatensprache: Ihre Aufbau und ihre Probleme (Strassburg: Trhbner, 1917). John Brophy and Eric Partridge, The Long Trail: What the British Soldier Sang and Said in the Great War of 19141918 (1930; London: Deutsch, 1965) is the most reliable source for British slang. Examples that I have drawn from war narratives have been verified in these glossaries. Published translations are so cited; all others are mine.

5. See Eric Partridge's exhaustive list of functions in Slang Today and Yesterday (1933; London: Routledge, 1970) 67.

6. Robert L Chapman, New Dictionary of American Slang New York: Harper and Row, 1986 xii.

7. Niceforo 16.

8. See Partridge 13 for the history and definition of the terms, and H.M. Fowler, A Dictionary of Modern English Usage (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1965) 315316 for a discussion of the various terms for jargon and slang.

9. Stuart Berg Flexner, preface, Dictionary of American Slang, by Robert L. Chapman (1960; New York: Harper and Row, 1986) xviii.

10. See especially DJchellette 232252 for French acronyms, and individual entries in Brophy. Most acronyms are jargon, but some become slang (see SNAFU, below). A First World War example is the German AEG (allgemeines Etappengeschw@tz=, general headquarters gossip) formed on Allgemeiner Elektrizit@tsgesellschaft (General Electric Company) of Berlin. See Mausser 52.

11. Chapman xv.

12. Partridge 2427.

13. Chapman xi.

14. See the chapter intitled "Chickenshit, an Anatomy" in Paul Fussell's Wartime (New York: Oxford UP, 1989) for a good analysis of scatological language among soldiers. Brophy briefly discusses the topic (2123).

15. In Chapman's view, the individual "merges both verbally and psychologically into the subculture that preens itself on being different from, in conflict with, and superior to the mainstream culture, and in particular to its assured rectitude and pomp" (xii).

16. Franz Schauwecker, The Furnace (Aufbruch der Nation), trans. R.T. Clark (London: Methuen, 1930) 212. The obsession of rear officers with nonessentials, specifically the maintenance of military customs and courtesies, is legendary. From an embarrassment of examples, see Erich Maria Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front, trans. A.W. Wheen (London: Putnam, 1929) 180182, and Robert Graves, Goodbye to All That (New York: Blue Ribbon Books, 1930) 156157.

17. See Michael Howard, "Men against Fire: Expectations of War in 1914," in Steven E. Miller, ed., Military Strategy and the Origins of the First World War (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1985) 4157, and Stephen Van Evera, "The Cult of the Offensive and the Origins of the First World War," in the same volume, 58107. On French military planning, see Allan Mitchell, Victors and Vanquished: The German Influence on Army and Church in France after 1870 (Chapel Hill: U North Carolina P, 1984).

18. Quoted in Fritz Fischer, War of Illusions: German Politics from 19111914 , trans. Marion Jackson (New York: Norton, 1975) 544. It is worth noting that most of the commanding generals in all three armies were cavalrymen.

19. J.M. Winter, The Experience of World War I (New York: Oxford UP, 1989) 18.

20. Eric J. Leed, No Man's Land: Combat and Identity in World War I (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1979) 12, 7175.

21. Aldington 292.

22. Ernst Jhnger, "Der Krieg als inneres Erlebnis," in Werke, 10 vols. (Stuttgart: Klett, 19601965) 7:11.

23. Leed 7880.

24. DJchelette iiiii.

25. Jacques Meyer, La vie quotidienne des soldats pendant la grande guerre (Paris: Hachette, 1966) 175.

26. See for example Otto Dix's superb engraving of a bedraggled squad returning from the trenches in his cycle Der Krieg.

27. Dauzat 4748. The word evidently dates to the First Empire. Meyer claims that the troops hated the name poilu and considered it a journalistic creation, using instead fantassin or bonhomme (1516).

28. The first three are listed in Bergmann 24, the last two in Mausser 18.

29. For accounts of the etymology, see Dauzat 5259, DJchelette 4344, Dictionnaire (Larousse) 41 and Brophy 88.

30. Bergmann 2324; Dauzat 5254.

31. Dauzat 160.

32. Leed 107.

33. Leed 111.

34. Philipp Witkop, ed., German Students' War Letters, trans. A.F. Wedd (London: Methuen, 1929) 369.

35. Marc Bloch, Memoirs of War, 191415, trans. Carole Fink (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1988) 150.

36. Fussell, Great War 124.

37. Fussell, Great War 124.

38. Niceforo 201202. The entire chapter "La magie des mots" is pertinent to my argument.

39. Niceforo 244249.

40. Mausser reports several other more complex phrases (4647) but I have never seen them or anything similar in any other text. Germans did refer to the uniform as a Leichenkleid (corpse's clothing) and to the groundsheet as a Leichentuch (winding sheet) or a Heldensarg (hero's sarcophagus). The British translators who translated many of the German war narratives of the late twenties and early thirties often rendered German trench slang into English trench slang, with unintentionally amusing results.

41. Bergmann 6.

42. Bergmann 67; Mausser 1921.

43. Bergmann 7.

44. There are numerous onomatopoeic names for shells, such as the French zimboum and zinzin, and the British "whizbang."

45. Mausser 2425; Bergmann 16. The dark German sense of the grotesque also produced M@hmaschine (mowing machine or reaper) and Fleischhackmaschine (flesh grinder) for machine gun.

46. Jean Norton Cru, TJmoins (Paris: Les Itincelles, 1929) 29.

47. Dauzat 9596. Many of the enormously popular picture postcards of the period carry poems and hymns to rosalie. See examples in Serge Zeyons, Le romanphoto de la Grande Guerre (Bruxelles: Iditions Hier et Demain, 1976) and Paul Vincent, Cartes postales d'un soldat de 1418 (Paris: Gisserot, 1988).

48. Partridge 14.

49. Niceforo 76; 8188.

50. Bergmann 32.

51. Meyer 220.

52. Mausser 6167.

53. Fussell, Great War 83.

54. Winter 137.

55. Bergmann 17; Alfred Hein, In the Hell of Verdun, trans. F.H. Lyon (London: Cassell, 1930) 234.

56. Brophy 18.

Author Ann P. Linder, contributed by Richard Schumaker

The Parados was the side of a trench farthest from the enemy.

- Did you know?