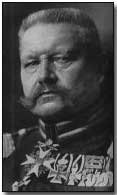

Primary Documents - Paul von Hindenburg on the Battle of Amiens, 8 August 1918

Reproduced below is an

extract from the post-war memoirs of the German Army Chief of Staff

Paul von

Hindenburg. In this extract von Hindenburg reflected upon

the effects of what transpired to be the onset of the final phase of the war, namely the Allied

advance to victory initiated by the Battle of Amiens

on 8 August 1918.

Reproduced below is an

extract from the post-war memoirs of the German Army Chief of Staff

Paul von

Hindenburg. In this extract von Hindenburg reflected upon

the effects of what transpired to be the onset of the final phase of the war, namely the Allied

advance to victory initiated by the Battle of Amiens

on 8 August 1918.

Click here to read an account of the battle by British newspaper journalist Philip Gibbs.

Paul von Hindenburg on the Battle of Amiens, 8 August 1918

On the morning of August 8th our comparative peace was abruptly interrupted.

In the southwest the noise of battle could clearly be heard. The first reports, which came from Army Headquarters in the neighbourhood of Peronne, were serious. The enemy, employing large squadrons of tanks, had broken into our lines on both sides of the Amiens-St. Quentin road. Further details could not be given.

The veil of uncertainty was lifted during the next few hours, though our telephone lines had been broken in many places. There was no doubt that the enemy had penetrated deeply into our positions and that batteries had been lost.

We issued an order that they were to be recovered and that the situation must everywhere be restored by an immediate counter-attack. We sent officers to ascertain precisely how matters stood, to secure perfect harmony between our plans and the dispositions of the various staffs on the shaken front. What had happened?

In a very thick haze a strong English tank attack had met with immediate success. In their career the tanks had met no special obstacles, natural or - unfortunately - artificial. The troops on this front had certainly been thinking too much about continuing the offensive and not enough of defence.

In any case, it would have cost us heavy losses to dig trenches and construct obstacles when we were in direct contact with the enemy, for as soon as the hostile observers noticed any movement, even if it were a matter of a few individuals, their artillery immediately opened fire.

It seemed our best plan to lie quietly in the high corn, without cover against enemy shells it is true, but at the same time safe from enemy telescopes. In this way we were spared losses for the time being, but ran the risk of suffering even greater losses if the enemy attacked.

It was not only that little work had been done on the first line; even less had been done on the support and rear lines. There was nothing available but isolated sections of trenches and scattered strong points. On these so-called quiet fronts the troops were not numerous enough for trench-digging on any large scale.

On this August 8th we had to act as we had so often acted in equally menacing situations. Initial successes of the enemy were no new experience for us. We had seen them in 1916 and 1917, at Verdun, Arras, Wytschaete and Cambrai. We had only quite recently experienced and mastered another at Soissons.

But in the present case the situation was particularly serious. The great tank attack of the enemy had penetrated to a surprising depth. The tanks, which were faster than hitherto, had surprised Divisional Staffs in their headquarters and torn up the telephone lines which communicated with the battle front.

The Higher Command-posts were thus isolated, and orders could not reach the front line. That was peculiarly unfortunate on this occasion, because the thick mist made supervision and control very difficult.

Of course our anti-tank guns fired in the direction from which the sound of motors and the rattle of chains seemed to come, but they were frequently surprised by the sight of these steel colossi suddenly emerging from some totally different quarter.

The wildest rumours began to spread in our lines. It was said that masses of English cavalry were already far in rear of the foremost German infantry lines. Some of the men lost their nerve, left positions from which they had only just beaten off strong enemy attacks and tried to get in touch with the rear again. Imagination conjured up all kinds of phantoms and translated them into real dangers.

Everything that occurred, and was destined to prove our first great disaster, is comprehensible enough from the human point of view. In situations such as these the old war-hardened soldier does not lose his self-possession. He does not imagine; he thinks!

Unfortunately these old soldiers were in a fast vanishing minority and, moreover, their influence did not always and everywhere prevail. Other influences made themselves felt. Ill humour and disappointment that the war seemed to have no end, in spite of all our victories, had ruined the character of many of our brave men.

Dangers and hardships in the field, battle and turmoil, on top of which came the complaints from home about many real and some imaginary privations! All this gradually had a demoralizing effect, especially as no end seemed to be in sight.

In the shower of pamphlets which was scattered by enemy airmen our adversaries said and wrote that they did not think so badly of us; that we must only be reasonable and perhaps here and there renounce something we had conquered. Then everything would soon be right and we could live together in peace, in perpetual international peace.

As regards peace within our own borders, new men and new governments would see to that. What a blessing peace would be after all the fighting! There was, therefore, no point in continuing the struggle.

Such was the purport of what our men read and said. The soldier thought it could not be all enemy lies, allowed it to poison his mind and proceeded to poison the minds of others.

On this August 8th our order to counter-attack could no longer be carried out. We had not the men, and more particularly the guns, to prepare such an attack, for most of the batteries had been lost on the part of the front which was broken through. Fresh infantry and new artillery units must first be brought up - by rail and motor transport.

The enemy realized the outstanding importance which our railways had in this situation. His heavy and heaviest guns fired far into our back areas. Various railway junctions, such as Peronne, received a perfect hail of bombs from enemy aircraft, which swarmed over the town and station in numbers never seen before.

But if our foe exploited the difficulties of the situation in our rear, as luck would have it, he did not realize the scale of his initial tactical success. He did not thrust forward to the Somme this day, although we should not have been able to put any troops worth mentioning in his way.

A relatively quiet afternoon and an even more quiet night followed the fateful morning of August 8th. During these hours our first reinforcements were hurried to the front.

The position was already too unfavourable for us to be able to expect that the counter-attack we had originally ordered would enable us to regain the old battle front. Our counter-thrust would have involved longer preparation and required stronger reserves than we had at our disposal on August 9th. In any case we must not act precipitately.

On the battle front itself impatience made men reluctant to wait. They thought that favourable opportunities were being allowed to slip, and proceeded to rush at insurmountable difficulties. Thus some of the precious fresh infantry units we had brought up were wasted on local successes without advantaging the general situation.

The attack on August 8th had been carried out by the right wing of the English armies. The French troops in touch with them on the south had only taken a small part in the battle.

We had to expect, however, that the great British success would now set the French lines also in motion. If the French pushed forward rapidly in the direction of Nesle, our position in the great salient projecting far out to the southwest would become critical. We therefore ordered the evacuation of our first lines southwest of Roye and retired to the neighbourhood of that town.

I had no illusions about the political effects of our de feat on August 8th. Our battles from July 15th to August 4th could be regarded, both abroad and at home, as the consequence of an unsuccessful but bold stroke, such as may happen in any war.

On the other hand, the failure of August 8th was revealed to all eyes as the consequences of an open weakness. To fail in an attack was a very different matter from being vanquished on the defence. The amount of booty which our enemy could publish to the world spoke a clear language.

Both the public at home and our Allies could only listen in great anxiety. All the more urgent was it that we should keep our presence of mind and face the situation without illusions, but also without exaggerated pessimism.

Source: Source Records of the Great War, Vol. VI, ed. Charles F. Horne, National Alumni 1923

A "creeping barrage" is an artillery bombardment in which a 'curtain' of artillery fire moves toward the enemy ahead of the advancing troops and at the same speed as the troops.

- Did you know?