Primary Documents - Manchester Guardian Newspaper on the Fall of Baghdad, 16 March 1917

Reproduced below is

war reporter Edmund Candler's despatch for the Manchester Guardian

newspaper, dated Friday 16 March 1917, in which he detailed the reaction of

the people of Baghdad to the

city's capture by the British

Army, led by

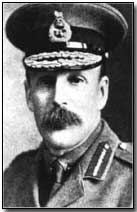

Sir Frederick Maude,

on 11 March 1917.

Reproduced below is

war reporter Edmund Candler's despatch for the Manchester Guardian

newspaper, dated Friday 16 March 1917, in which he detailed the reaction of

the people of Baghdad to the

city's capture by the British

Army, led by

Sir Frederick Maude,

on 11 March 1917.

Appointed by the Chief of the Imperial General Staff in London, Sir William Robertson, in the wake of the earlier disaster at Kut, Maude's instructions were brief and somewhat unusual: effectively to hold his existing line and to do nothing. In particular Robertson was emphatic that Maude should not make demands for resources otherwise intended for the Western Front.

A cautious and consistent rather than spectacular commander, Maude nevertheless led his forces in a series of victories up the Tigris, beginning with the Second Battle of Kut and leading to the capture of Baghdad.

Ironically the British - and Robertson in London - found themselves a victim of their own success. Maude's continuing unbroken run of victories ensured that no scaling down of operations in Mesopotamia could feasibly be considered as Maude's reputation grew in the Muslim world.

Thus British operations were widened to stem threats from Turk forces on the Euphrates, Diyala and Tigris rivers. Following success at Baghdad, April 1917 saw Maude triumph again, at Samarrah, and he continued his offensive at Ramadi and Tikrit before calamity struck in early November 1917.

Struck down with cholera, probably via contaminated milk (rather than by poisoning as was speculated by some at the time), Maude died on 18 November 1917 and was replaced by General William Marshall.

Click here to read the official Austro-German report detailing the British capture of Baghdad, written by Dr Gaston Bodart. Click here to read Maude's official despatch detailing British Army operations between December 1916 and March 1917.

The Fall of Baghdad by Edmund Candler, Manchester Guardian, 16 March 1917

Our vanguard entered Baghdad soon after nine o'clock this morning. The city is approached by an unmetalled road between palm groves and orange gardens.

Crowds of Baghdadis came out to meet us: Persians, Krabe, Jew, Armenians, Chaldeans and Christians of diverse sects and races. They lined the streets, balconies and roofs, hurrahing and clapping their hands. Groups of schoolchildren danced in front of us, shouting and cheering, and the women of the city turned out in their holiday dresses.

The people of the city have been robbed to supply the Turkish army for the last two years. The oppression was becoming unendurable, and during the last week it degenerated into brigandage. I am told that the mere mention of the British was punishable, and the people were afraid to talk freely about the war.

It appears that the enemy abandoned all hope of saving the city when we effected the crossing of the Tigris on February 23. After that date, the Turkish government requisitioned private merchandise wholesale, and despatched it by train to Samara. Thirty or forty thousand pounds worth of stuff is believed to have been officially looted, including five thousand sacks of flour.

The German Consul left weeks ago, and the Austrian two days since. The bridge of boats, the Turkish army clothing factory and Messrs Lynch's offices were blown up or otherwise destroyed last night, and the railway station, the Civil Hospital and most British property except the Residency, which had been used as a Turkish hospital, were either gutted or damaged.

As soon as the gendarmery left at two o'clock this morning, Kurds and others began looting. As we entered from the east this morning, they were rifling, and among the first citizens we met were merchants who had run out to crave our protection.

Regiments were detailed to police, the bazaar, and houses and pickets and patrols were allotted, but there was much that it was too late to save. Many shops had been gutted, and the valuables had all been cleared. The rabble was found busily engaged in dismantling the interiors, tearing down bits of wood and iron and carrying off bedsteads. They had even looted the seats from the public gardens.

Our entry was very easy and unofficial, and it was clear that the joy of the people was genuine. No functionaries came out to meet us. There was still fear of reprisals. Our own attitude was characteristic. There was no display, or attempt at creating an impression.

The troops entered, dusty and unshaven, after several days hard fighting. Fighting between the 7th and 10th had been heavy, and extraordinary gallantry was shown in crossing the Diala river.

Source: Source Records of the Great War, Vol. V, ed. Charles F. Horne, National Alumni 1923

A 'Tour' was a period of front-line service.

- Did you know?