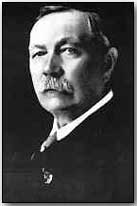

Primary Documents - The Battle of Cambrai by Arthur Conan Doyle, 19 November 1917

Reproduced below is a

portion of

Arthur Conan Doyle's summary

of the British-led

Battle

of Cambrai in November 1917.

Reproduced below is a

portion of

Arthur Conan Doyle's summary

of the British-led

Battle

of Cambrai in November 1917.

Conan Doyle's account emphasised the role massed tanks played during the battle which, on account of the surprise tactics employed, necessitated the absence of the usual preliminary artillery bombardment. He noted that initial progress was rapid, but slowed in the face of determined German resistance.

Click here to read German Army Chief of Staff Paul von Hindenburg's reaction.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle on the Battle of Cambrai

We shall now descend the British battle line to the section which extends from Bullecourt in the north to Villers-Ghislain in the south, opposite to the important town of Cambrai, some seven miles behind the Hindenburg Line.

It was here that Field-Marshal Haig had determined to strike his surprise blow, an enterprise which he has described in so lucid and detailed a dispatch that the weary chronicler has the rare experience of finding history adequately recorded by the same brain which planned it.

The plan was a very daring one, for the spot attacked was barred by the full unbroken strength of the Hindenburg main and support lines, a work so huge and solid that it seems to take us back from these superficial days to the era of the Cyclopean builder or the founder of the great monuments of antiquity.

These enormous excavations of prodigious length, depth, and finish are object lessons both of the strength of the Germans, the skill of their engineers, and the ruthlessness with which they exploited the slave and captive labour with which so much of it was built.

Besides this terrific barricade there was the further difficulty that the whole method of attack was experimental, and that to advance without artillery fire against such a position would appear to be a most desperate venture.

On the other hand it was known that the German line was thin and that their man-power had been attracted northwards by the long epic of the Passchendaele attack. There was a well-founded belief that the tanks would prove equal to the task of breaking the front, and sufficient infantry had been assembled to take advantage of any opening which might be made.

The prize, too, was worth a risk, for apart from the possibility of capturing the important centre of Cambrai, the possession of the high ground at Bourlon would be of great strategic value.

The enterprise was placed in the hands of General Byng, the famous leader of the Third Cavalry Division and afterwards of the Canadian Corps, who had taken Allenby's place at the head of the Third Army. Under him were some of the most seasoned fighting material in the army.

The troops were brought up stealthily by night, and the tanks which were crawling from every direction towards the trysting-place were carefully camouflaged. The French had been apprised of the attack, and had made arrangements by which, if there were an opening made to the south, some of their divisions should be available to take advantage of it.

The tanks were about four hundred in number and were under the separate command of General Ellis, a dashing soldier who inspired the utmost enthusiasm in his command. It had always been the contention of the tank designers in England that their special weapon needed what it had never yet found, virgin ground which was neither a morass nor a wilderness of shell-holes.

The leading lines of tanks had been furnished with enormous fagots of wood which they carried across their bows and which would be released so as to fall forward into any ditch or trench and to form a rude bridge. These ready-made weight-bearers were found to act admirably.

One difficulty with which the operations were confronted was that it was impossible for the guns to register properly without arousing suspicion. It was left to the gunners, therefore, to pick up their range as best they might after the action began, and this they did with a speed and accuracy which showed their high technical efficiency.

North of the main battle the Fifty-sixth Division kept up a spirited Chinese attack all day. The real advance was upon a frontage of six miles which covered the front from Hermies in the north to Gonnelieu in the south.

Every company of the advancing units had been instructed to fall in behind its own marked tank. At 6.20, just after dawn, in a favouring haze, General Ellis gave the signal, his iron-clad fleet flowed forward, the field of wire went down with a long splintering rending crash, the huge fagots were rolled forward into the gaping ditches, and the eager infantry crowded forward down the clear swathes which the monsters had cut.

At the same moment the guns roared out, and an effective smoke-barrage screened the whole strange spectacle from the German observers.

The long line of tanks magnified to monstrous size in the dim light of early dawn, the columns of infantry with fixed bayonets who followed them, all advancing in silent order, formed a spectacle which none who took part in it could ever forget.

Everything went without a hitch, and in a few minutes the whole Hindenburg Line with its amazed occupants was in the hands of the assailants. Still following their iron guides, they pushed on to their further objectives.

They made a fine advance, but were held up by the strongly organized village of Flesquieres. The approach to it was a long slope swept by machine-gun fire, and the cooperation of the tanks was made difficult by a number of advanced field-guns which destroyed the slow-moving machines as they approached up the hill.

If the passage of the Hindenburg Line showed the strength of these machines the check at Flesquieres showed their weakness, for in their present state of development they were helpless before a well-served field-gun, and a shell striking them meant the destruction of the tank, and often the death of the crew.

It is said that a single Prussian artillery officer, who stood by his gun to the death and is chivalrously immortalized in the British bulletin, destroyed no less than sixteen tanks by direct hits.

At the same time the long and solid wall of the chateau formed an obstacle to the infantry, as did the tangle of wire which surrounded the village. The fighting was very severe and the losses considerable, but before evening the Highlanders had secured the ground round the village and were close up to the village itself.

The delay had, however, a sinister effect upon the British plans, as the defiant village, spitting out flames and lead from every cranny and window, swept the ground around and created a broad zone on either side, across which progress was difficult and dangerous.

It was the resistance of this village, and the subsequent breaking of the bridges upon the canal which prevented the cavalry from fulfilling their full role upon this first day of battle. Nonetheless as dismounted units they did sterling work, and one small mounted body of Canadian Cavalry, the Fort Garry Horse from Winnipeg, particularly distinguished itself, getting over every obstacle, taking a German battery, dispersing a considerable body of infantry, and returning after a day of desperate adventure without their horses, but with a sample of the forces which they had encountered.

It was a splendid deed of arms, for which Lieutenant Henry Strachan, who led the charge after the early fall of the squadron leader, received the coveted cross.

At Marcoing the bridge was captured intact, the leading tank shooting down the party who were engaged in its demolition. At Mesnieres, which is the more important point, the advancing troops were less fortunate, as the bridge had already been injured and an attempt by a tank to cross it led to both bridge and tank crashing down into the canal.

This proved to be a serious misfortune, and coupled with the hold-up at Flesquieres, was the one untoward event in a grand day's work. Both the tanks and the cavalry were stopped by the broken bridge, and though the infantry still pushed on their advance was slower, as it was necessary to clear that part of the village which lay north of the canal and then to go forward without support over open country.

Thus the Germans had time to organize resistance upon the low hills from Rumilly to Crevecoeur and to prevent the advance reaching its full limits.

Source: Source Records of the Great War, Vol. V, ed. Charles F. Horne, National Alumni 1923

A 'Toasting Fork' was a bayonet, often used for the named purpose.

- Did you know?