Memoirs & Diaries - 17-21

I landed in France with a

medical unit attached to the 7th Division in November 1914. I was a

boy just turned seventeen, straight from school, and all the thrill of

romance and adventure was on me.

I landed in France with a

medical unit attached to the 7th Division in November 1914. I was a

boy just turned seventeen, straight from school, and all the thrill of

romance and adventure was on me.

The story-books were coming true, and by an extraordinary piece of luck I was privileged to be a participator. How enviously my school friends had written to me when they heard that we were definitely under orders to proceed, after a bare three months' training, on active service.

There was a wonderful march through the streets of Southampton at midnight, amid crowds of cheering and delirious people. A woman had thrown her arms round me and kissed me, thrusting cigarettes into my pocket. We were inundated with gifts.

No knight of old went to war with a more exalted heart or a purer enthusiasm. I was only seventeen, and many who might have known better were just the same.

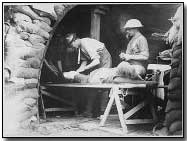

At Poperinghe and other places we were soon hard at work with the wounded from Ypres. As I had already done duty on an ambulance train in England, this was nothing new to me, except that now the casualties poured into the clearing hospital day and night; there was no rest; the smell of blood, gangrened wounds, iodine, and chloroform filled the twenty-four hours.

Sights that made older men sick with horror served only to harden my determination, and, though often terrified and worn out by the unaccustomed heavy labour, I grew more and more anxious to play my part.

As the fighting died down, and our work grew less, a group of us, similar in age and station, gradually became dissatisfied with what we thought our inglorious share in the War. We felt we were not soldiering. The glamour was wearing off.

Winter came and went, and in the big building, an old convent, where the hospital was, we spent our spare time devising schemes for getting into a combatant branch of the Army. Strange as it may seem, we were not dismayed by what we had seen of the pain and suffering, the groans and agonies of the sick, wounded, and dying. We were used to all this, but we were not callous.

It was, indeed, a dull monotonous time, scrubbing floors, washing windows, cleaning latrines, doing a hundred odd jobs with compensations of a sort in the cafes of the town near by. I learned to drink, I could already swear as fluently as any other Tommy, and occasionally grew bold enough to kiss a Flemish girl at the cottage where we took our washing.

The sudden rush of work and the excitement that accompanied the Battle of Neuve-Chapelle and the disastrous attack on Aubers Ridge did not change our minds. Several of us applied for commissions, and we counted the days till they came through, and, one by one, the lucky ones of us returned to England in the early summer of 1915.

I joined a Territorial reserve brigade of R.F.A. just being formed, and before my eighteenth birthday appeared at home resplendent in a second lieutenant's uniform.

There were several of us in the brigade mess and,

having little to do, we spent the time ragging about like the schoolboys we

were, boasting of our female acquaintances picked up easily enough in the

large town where we were quartered, teaching one another how to drink and

still retain a semblance of sobriety, doing anything, in fact, which

youthful exuberance could suggest, sometimes going even further than that.

There were several of us in the brigade mess and,

having little to do, we spent the time ragging about like the schoolboys we

were, boasting of our female acquaintances picked up easily enough in the

large town where we were quartered, teaching one another how to drink and

still retain a semblance of sobriety, doing anything, in fact, which

youthful exuberance could suggest, sometimes going even further than that.

A few horses arrived and we learned to ride. We did gun-drill on wooden guns, and took imaginary batteries into action on hillsides outside the town. We went on courses of gunnery, signalling, and other things, and in a few months were pronounced trained and fit to go abroad.

The little we knew, and mostly theory at that, was just enough to give us boundless confidence in our ability. Certificates of proficiency were as easy to obtain as autumn apples.

It was a mad merry time while it lasted, but the second winter of the War came on, and the time came near for going out again. The majority of us, I think, were anxious to go, though our reasons were no doubt selfish and vainglorious.

The time came soon enough, and after a cold February journey of several days, three of us joined our first-line brigade in France. The division was at rest, which meant that we spent our time exercising horses, slipping and squelching in muddy fields all day, playing bridge in the evening, while it rained and rained.

Orders came in a week or so that we were going into action, but we newly joined subalterns found it politic to keep our jubilation to ourselves.

The battery left the village one morning at two o'clock. It was still dark, of course, and raining. Riding in the wet at a walk all day long is by no means pleasant, but even now I can remember the feeling of exultation that filled me. At last I was going to see some real war.

Three days later we were in action near Albert. I soon found my hastily

learned theories of very little use.

Three days later we were in action near Albert. I soon found my hastily

learned theories of very little use.

For one thing, our training had been for open warfare; for another, there was a great scarcity of ammunition. We were allowed twenty-one rounds a week; our reply to an infantry S.O.S. signal was to fire three rounds!

I was up at the battery for some days before I heard an enemy shell. It was all so quiet I couldn't believe that this was being under fire. I don't think any shells came near our battery all the time we were in, which was not very long, as it happened, for we were withdrawn to undergo intensive training for the big offensive.

I still felt as though the War was eluding me, especially during some weeks I spent in hospital as the result of a slight wound received, not in action, but in playing football against a rival battery. When the training became really intensive, even the hardest bitten veterans began to grumble and express desires to get back into the line for a quiet life.

Rumours regarding the "push" were thick for a long time. Before we left our rest billets we knew the front our division was to attack, what our objectives were and the rest of it. In those days there was little secrecy, and the constant postponements must have given plenty of scope to German spies. Numbers of human lives were to pay for this later, but at the time the feelings of optimism everywhere rivalled those of 1914.

One June night in 1916 we occupied our allotted gun-pits opposite Thiepval, and began firing in real earnest. No more limits, no more peace and quiet. Batteries were scattered all over the white scarred slopes beyond the Ancre, firing day and night. We were engaged chiefly on wire-cutting.

We had a new O.C., an unpleasant touchy man who knew very little about his job. To be in the observation post with him was an experience that few of the younger officers or any of the men could endure for long. He cursed continually, swore that he hadn't an efficient man in the battery, declared that the observers were blind, the gunners unable to shoot, and so on. As a matter of fact, the gunners, though inexperienced, were a splendid lot, full of enthusiasm.

The pounding that the Boche trenches received in that last week of June was

unprecedented. Everyone confidently expected that no one could live under

it.

The pounding that the Boche trenches received in that last week of June was

unprecedented. Everyone confidently expected that no one could live under

it.

Orders were sent to the wagon lines to have the gun teams ready for the advance. The infantry were to go straight through when zero hour came, and our advance position was clearly marked on the map.

As the bombardment grew, so did the retaliation. We had several casualties; the one which most affected me was the death of our senior lieutenant. He was literally blown to pieces by a shell on the battery position, bits of flesh besmearing one of the gun-pits and covering the gun in blood. The remains were collected in a sandbag and buried.

July 1st came, but Thiepval was not captured. Division after division went in and came out, but a few lines of trenches were all that many thousands of casualties had been able to buy. The expected orders to lift the barrage never came to the battery , and it was soon obvious that the attack was a failure.

Rumours of success in other places filled the air, but as the days went by it became clear that a frontal assault on such a place was doomed to defeat. We took turns up at the O.P., on the battery, and down at the wagon lines.

German shelling increased on the roads and the battery position, until it became a dangerous journey that the ammunition teams had to make daily. It was a long time before I felt any fear.

At first I had, like many others, been afraid of being afraid, but I soon learned there was no danger of that. The excitement and thrill of battle were on me. I was too young to think of anything else.

As the weeks passed and we did not advance, the unpleasant relations between the O.C. and some two or three of us increased. Many times I prayed heartily for a wound as the only means of escaping from him. This second reason for welcoming danger soon outweighed the first. There is pettiness in war, as in all other human activities.

Some time later I was fortunate enough to get myself transferred to a trench

mortar battery, then popularly known as "The Suicide Club". Here I found

myself in as jolly a crowd as I ever met in the War, and amongst whom I

spent my happiest times. For they were happy times, in spite of the greater

discomfort and undoubtedly greater danger than I had experienced in a field

battery.

Some time later I was fortunate enough to get myself transferred to a trench

mortar battery, then popularly known as "The Suicide Club". Here I found

myself in as jolly a crowd as I ever met in the War, and amongst whom I

spent my happiest times. For they were happy times, in spite of the greater

discomfort and undoubtedly greater danger than I had experienced in a field

battery.

The small guns fired a 60-lb. bomb for a maximum distance of 500 yards, and consequently were usually in or near the front-line trench. The bombs did great damage to wire and trenches and naturally enemy retaliation was prompt and heavy whenever we fired.

The first time I was in action with them, we were at a quiet spot on the Front, and lived in a broken-down house a mile from the front line. One evening, just after supper, a 4.2 shell came through the wall into the room, bursting at once.

We were thrown on the ground, the candles extinguished, and bits of plaster and falling brick showered on us. The door and window of the room, frames and all, were blown out, but, marvellously, no one was hurt.

It was from this time that I began to experience what fear was. This sudden shock (I trembled for an hour afterwards) gave me a completely new outlook on life, life and war being, of course, synonymous terms. I crouched at the sound of a shell, found myself on a dark, quiet night in the trenches shivering with terror at what might happen.

A distant machine-gun rattle would make me jump, and I often found it impossible to suppress such starts when not alone. I began to wonder if I was becoming a coward.

Soon after this we were wire-cutting opposite Beaumont-Hamel. The trench conditions here in late October were appalling. Long communication trenches, full of thick sticky mud often waist deep and constantly shelled, led up to a similar front line.

Good dug-outs were few, and the heavy rain made things about as bad as they could be. During the day we fired at the German wire and in the evenings returned to our billets in the smashed-up village of Mailly-Maillet. A 9.2 howitzer was in our back garden, and the whole dilapidated house shook to its foundations every time it fired.

In spite of this, and the shelling of the village, we led a seemingly

care-free life, spending most of the night playing poker and vingt-et-un,

drinking enormous quantities of whisky, cursing the War, and wondering if we

should ever go on leave.

In spite of this, and the shelling of the village, we led a seemingly

care-free life, spending most of the night playing poker and vingt-et-un,

drinking enormous quantities of whisky, cursing the War, and wondering if we

should ever go on leave.

Beaumont-Hamel was taken on November 13th, and, as we had nothing to do, we volunteered to take stretcher-bearing parties over to the captured trenches. We crossed the old No Man's Land in daylight, and, in spite of our being unarmed and carrying stretchers, were heavily fired on, and lost several men.

It grew wetter and more misty, and just as we reached the newly won trenches, a German counter-attack started. We cumbered the trench rather uselessly until some of us were able to get hold of rifles from the killed and join in repelling the attack. There was little to be seen in the inferno of bursting shells ahead, though a few shadows in the mist were undoubtedly the advancing Boches.

They never came any nearer, and gradually it became apparent that they had been kept off. Even so it was dusk before we could get away with our burdens, the number of whom had been vastly increased during the day. During the attack shells had come into the trench every minute, and it was completely blocked with dead and wounded.

We removed as many as possible during the night, having more casualties ourselves on the way back from a raking machine-gun fire.

It was not till four days before Christmas that we came out of the line definitely for a real rest, the first since early June. Six months of action!

The crowning moment came when my turn for leave arrived at last. It was on the first day of the New Year 1917. There are some things about the War one can never tell, and this is one. It is enough to say that it was a very different young officer who came home from the one who had gone out eleven months before. Mentally, physically, morally, I was changed, and I felt it myself very strongly.

Further periods of action followed in various places, but my diary entries

for this time record little beyond the cold, frosty weather, an occasional

casualty, a note of a trip to Amiens. For the rest, there was nothing but

the deadly monotony of trench warfare.

Further periods of action followed in various places, but my diary entries

for this time record little beyond the cold, frosty weather, an occasional

casualty, a note of a trip to Amiens. For the rest, there was nothing but

the deadly monotony of trench warfare.

None of us could understand why - just as the year before - the spring and early summer came and went without any resumption of the offensive. Not that we worried. We were one and all only too pleased to be in a quiet place, with nothing beyond a raid or two now and then to disturb us.

In July, however, there was a recrudescence of activity. We took over from the Belgians at Nieuport, but the projected attack was prevented by the German capture of our jumping-off ground beyond the Yser Canal.

It was here that we first met the new "mustard" gas. Our division suffered heavily; men dropped in the streets, on the roads, in billets, often many hours afterwards. New respirators had to be served out.

Meanwhile the Third Battle of Ypres was continuing. We came into the Salient in the autumn, and, there being no scope for trench mortars, we were scattered among field batteries, on ammunition dumps, and other jobs mostly as inglorious as they were necessary.

Not that I personally had any longer any illusions about glory. In common with most others, I considered going up the line little more than a horrible necessity, the odd periods of rest in uncomfortable cold tents or huts surrounded by seas of mud a heavenly respite almost too good to be true.

I doubt if anyone who has not experienced it can really have any idea of what the Salient was like during those "victories" of 1917. The bombardments of the Somme the year before were nothing to those round Ypres. Batteries jostled each other in the shell-marked waste of mud, barking and crashing night and day.

There were no trees, no

houses, no countryside, no shelter, no sun.

There were no trees, no

houses, no countryside, no shelter, no sun.

Wet, grey skies hung over the blasted land, and in the mind a gloomy depression grew and spread.

Trenches had disappeared. "Pill-boxes" and shell holes took their place. We never went up the line with a working party with any real expectation of returning, and there was no longer any sustaining feeling that all this slaughter was leading us to anything. No one could see any purpose in it.

I remember watching a company of infantry marching up the greasy duckboard track one evening. A young subaltern with them recognized me. We had been in the same sector once south of Arras - "Our turn now," he said, without a smile. "Bye-bye." They marched on, bowed, hopeless.

I had all sorts of escapes; in fact they were so frequent that I got into a strange frame of mind, and became careless. It seemed as if I couldn't bother to try and avoid unnecessary danger. The only matters of importance were whether the rations would come up promptly and if the bottle of whisky I had ordered would be there.

It was for me the worst part of the War. Even now it looms like a gigantic nightmare in the back of my mind. Rest came again, and my third leave. I did not enjoy it. I was bitterly unwilling to go back. How I envied those who had never gone out or had never joined the Army!

In February 1918 we were in the Salient again, this time with new 6-inch mortars. Attacks and raids were fairly frequent, but our work was mechanical and had no interest for any of us. We hated our turns in the trenches, and thought only of when we should come out.

Most of my friends had left, some for the Flying Corps, the majority for ever. Gas, death, and wounds had accounted for them. New officers and men came out, the proceeds of conscription, but, whatever their quality, they were not like the old lot. How could they be?

I began to feel like one who had outlived his time, and grew more and more

depressed. I certainly had no hope of surviving much longer. The odds were

heavily against it.

I began to feel like one who had outlived his time, and grew more and more

depressed. I certainly had no hope of surviving much longer. The odds were

heavily against it.

After the big attack on the Somme in March, we evacuated the Salient. It presented a strange empty and quiet appearance as we marched out. I think many of us could have sat down on the duckboards and wept that April day.

All the fruits of the appalling struggle of the year before were given up in a night. We were sent to field batteries again, and there was some excitement in the new open fighting.

We would trot calmly into action in full view of the Boches as steadily as on parade. But we were never left long in peace, and had to endure a great deal of heavy shelling and gas bombardment.

At last, one early morning, at the beginning of the last German attack south of Ypres (as I learned later), in the middle of an S.O.S. a perfect deluge of 4.2's rained on the unsheltered battery.

I was one of the first to be hit, and, despite the pain of the wound and the terror that I should bleed to death before I was attended to, I kept on repeating to myself, "It's over now. It's over now."

And so it was, for me at any rate. When I came out of hospital many months later the Armistice had been signed. I was just twenty-one years of age, but I was an old man - cynical, irreligious, bitter, disillusioned. I have been trying to grow young ever since.

George F. Wear enlisted in the R.A.M.C. on August 9th, 1914; went to France with the 7th Clearing Hospital at the end of October, and returned to take up a commission in the R.F.A. in July 1915.

In February 1916 he returned to France, joining the 49th Division. He served with them till April 1918, when he was wounded near Kemmel, and he was afterwards in hospital in London and Newcastle till August 1919.

The chief engagements he took part in were the Somme, 1916; Ypres, 1917; and Ypres 1918.

First published in Everyman at War (1930), edited by C. B. Purdom.

Photographs courtesy of Photos of the Great War website.

French tanks were used for the first time in battle on 17 April 1917, when the 'Char Schneider' (as they were known) was used during the Second Battle of the Aisne.

- Did you know?