Memoirs & Diaries - Bravery in the Field?

In the summer of 1918, when

I was twenty-one years old, I rightly considered myself a war veteran.

I had seen one after another of my friends "go West" at the Somme in 1916,

both in the heat of July and August at High Wood and Delville Wood, and in

the terrible slough of despond around the Butte de Warlencourt in November.

In the summer of 1918, when

I was twenty-one years old, I rightly considered myself a war veteran.

I had seen one after another of my friends "go West" at the Somme in 1916,

both in the heat of July and August at High Wood and Delville Wood, and in

the terrible slough of despond around the Butte de Warlencourt in November.

I had lived for weeks on bully beef and biscuits as one of the victorious army which "chased" the Germans at Arras in April and May 1917, till it was brought to a halt by the Hindenburg Line.

For months during the winter of 1917-18 I had never been further away from the line than in "rest" billets at Ypres. By some lucky chance our battalion missed the disastrous March 21st, 1918, when the enemy broke through in the south. Nevertheless, I had taken part in almost hand-to-hand fighting in Flanders for a whole week during the month of April.

With such a campaign behind me I was a careful and experienced soldier with an expert knowledge of all the strange sounds and smells of warfare, ignorance of which may mean death to the man who is not quick to apprehend their meaning.

My hearing was attuned to every kind of explosion from the hacking cough of bombs to the metallic clanging of 5.9 shells bursting in re-echoing valleys. My nostrils were quick to detect a whiff of gas or to diagnose the menace of a corpse disinterred at an interval of months.

The strain of the summer of 1918, with its big outbreak of influenza, tended to a mood of utter war-weariness. I had entered the Army grudgingly, but in obedience to irresistible social pressure. I had hated strife, yet lacked the courage to be a pacifist.

Military service seemed not so much an adventure as a disagreeable, inescapable task. I coveted neither rank nor glory, and my twenty-first birthday found me in the ranks of a Scottish regiment performing the duties of that military maid-of-all-work, acting lance-corporal (unpaid).

My mood during 1918 changed from a stoicism which looked on and, with difficulty, conquered fear, to one of blank despair which tried to mask itself in a spirit of care-free military enterprise. I was in a frenzy for something to happen - wounds, death, anything! There were various contributory circumstances.

I had received a letter from home, stating that my father expected to be conscripted. I had seen a father and son in France together. The son now lay trussed in his groundsheet at Passchendaele and the sight of the father was not easily forgotten.

Perhaps, also, the fact that I had suffered the ignominy of 7 days No.1 Field Punishment for a purely imaginary military "crime" helped my disgust. Whatever the cause, I found myself volunteering for every job that came my way, and running unnecessary risks in a thoroughly unsoldierlike manner.

In

September 1918 our battalion was occupying a front-line position which had

just been vacated by the Germans. At this stage of the War Jerry was

fighting a magnificent rearguard action.

In

September 1918 our battalion was occupying a front-line position which had

just been vacated by the Germans. At this stage of the War Jerry was

fighting a magnificent rearguard action.

The day before leaving this position he had repulsed our attack, inflicting heavy losses. Next morning he was nowhere to be seen. Cautiously we crept over the parapet in an uncanny silence, advancing in little groups.

Just in front lay a Highlander with face upturned, red bubbles at mouth and nostrils. Further on a young subaltern, a few weeks from home, had fallen, striking an attitude with walking stick outstretched. Their faces were still quite recognizable, the weather being cool. A couple of hundred yards from our starting-point lay the main body of our comrades who had fallen the previous day.

Their bodies were strewn in every direction. Dozens were heaped around a pitiful little 2-foot trench which they had dug. Many of them were without boots, for the Germans in retiring had taken sufficient time to satisfy their crying need for good footwear.

Our objective, a ridge about a mile off, was reached without opposition. We dug in on the crest of a hill overlooking a deep valley. Along the bottom of the valley ran a canal. Soon after dusk our patrols penetrated to the canal bank, where they were peppered by rifles and machine guns.

Even to the brass-hats at Corps Headquarters in some distant chateau, it was obvious that the passage of the canal would be a difficult operation. A hurried decision was taken that before attempting any general advance we must ascertain the disposition of the enemy.

For this purpose it was proposed to send a patrol consisting of an officer, a sniper, and a signaller to reconnoitre in daylight next day. Without much difficulty I secured the post as signaller. I was glad to find the officer was a cool youngster of about my own years. I had known him whilst he was in the ranks. He gave me a hearty welcome when I reported at the commanding officer's dug-out for instructions.

The

careful instructions of the colonel suggested our task to be one of some

importance and some danger. On leaving we received stiff tots of

whisky.

The

careful instructions of the colonel suggested our task to be one of some

importance and some danger. On leaving we received stiff tots of

whisky.

Here was confirmation of my suspicion. All doubt was expelled when the sergeant-major handed me a water-bottle with rum as part of the equipment of the expedition.

My duty as signaller was to lead a signal wire all the way travelled by the patrol, so that we would be in continuous communication with our unit. I was carrying three drums of wire, a telephone, a rifle, and infantry kit.

Climbing out of our front-line trench in the dark between four and five o'clock in the morning, we proceeded gently downhill to the towpath of the canal, where the previous patrols had been fired on. Nothing disturbed the stillness of the early morning as we walked warily forward. The first signal station was soon established in a gun-pit in a small hillock overlooking the canal.

Our plan was to spend the day there scouring the further bank with the telescope to locate enemy positions. By wartime standards, we had comfortable quarters, and considered ourselves entitled to celebrate our safe arrival by broaching the rum. I was physically weak after the exertions of the previous day or two. Perhaps the rum was particularly potent.

Anyhow I awoke in broad daylight with a raging thirst, a confused head, and a Webley revolver staring me in the face. Stone, the subaltern, threatened with curses that he would shoot me if I didn't keep awake. I sat up and tried to appear interested.

He and I were good friends. I suggested breakfast and instantly my somnolence was forgiven. In my haversack I had a selection of eatables from a parcel just received from home. Out came a piece of cake, a black pudding, a tin of cafe-au-lait, and a "Tommy" Cooker.

It was the work of a minute to commandeer the water in the sniper's bottle, and a brew of coffee was soon prepared. A short time later slices of black pudding were sizzling in the mess-tin lid. Small tots of rum completed the banquet. Once more we could resume interest in the War.

Through

the telescope Smithy the sniper scanned the tow-path of the canal while

Stone gave me in an undertone some of the more scandalous episodes of a

recent leave.

Through

the telescope Smithy the sniper scanned the tow-path of the canal while

Stone gave me in an undertone some of the more scandalous episodes of a

recent leave.

He was interrupted by Smithy, who put a finger to his lips and motioned Stone towards the telescope.

There was little need of the telescope, for about 100 yards from us on our side of the canal was a small emplacement with two machine guns. A German sentry sat behind the guns keeping a lazy look-out.

Two other Germans were a few yards from him, with tunics off and shirts open, washing on the canal bank. Evidently our presence was unsuspected. Beside the emplacement, a small plank bridge had been thrown across the canal.

Stone and I exchanged understanding glances. Slowly he led the way on all fours through the narrow sap leading from our gun-pit to the open. I divested myself of the telephone headpiece, which I handed to Smithy, who nodded comprehendingly.

Grabbing my rifle I followed Stone, lying fiat when clear of the sap. The ground outside was uneven and there were low shrubs affording some concealment, but we crept forward on our stomachs till half the distance was traversed.

"I say, Jimmy" - it was a furtive whisper - "what next?" There was no answer for a moment whilst he examined his revolver. In dumb show he looked at my rifle to see if the safety catch was up. "Come a little closer," he whispered, "and we'll try to capture them. Brigade wants prisoners for information. You cover the two on the bank while I rush the sentry".

Cautiously we tried to carry this out and just when I had judged it was nearly time to put the plan to the test there was an excited shout from one of the bathers, who was pulling on his tunic and had looked in our direction. Both of them rushed towards the sentry.

Quick as a flash Stone and

I ran forward. But the Germans were quicker. Over the plank

bridge they scuttled, throwing themselves flat on the ground on the other

side. A bullet whistled past us as we jumped into the little

emplacement containing their abandoned machine guns. I fired a round

or two of my rifle into the opposite bank but there was no answering fire.

They lay low and probably crawled away to safety.

Quick as a flash Stone and

I ran forward. But the Germans were quicker. Over the plank

bridge they scuttled, throwing themselves flat on the ground on the other

side. A bullet whistled past us as we jumped into the little

emplacement containing their abandoned machine guns. I fired a round

or two of my rifle into the opposite bank but there was no answering fire.

They lay low and probably crawled away to safety.

The ground on the other side was undulating and offered good cover. Stone had taken down their guns and turned them the other way round. For an hour we awaited events, but all was still and peaceful except for a breeze rippling the canal.

A short distance to our right were the remains of a stone bridge which had been mined. A good road led to it on each side. During the hour which had elapsed we had watched the road on the German side without seeing any signs of life. Stone was getting restless as we were out to spot Germans and as yet knew nothing about the troops across the way.

He sent me back to bring our friend the sniper to our new post and to extend the telephone. This was easily done and Stone was soon reporting progress to the colonel at the other end of the wire.

I could see that my own daft mood had its counterpart in Stone's. It was, therefore, no surprise to me when he invited me to "walk the plank" and reconnoitre the other side. Judging our three Boches to be a forgotten outpost, we made boldly on foot for the road. I had still remaining one drum of telephone wire which was connected to our line in the emplacement. The telephone was slung on my shoulder.

On we walked, looking to right and left, but seeing nothing. Half-way up the hill we were brought to a halt, as the drum of wire was exhausted. It was reassuring nevertheless to connect the telephone and find we were still in contact with our battalion. In the ditch ran a number of German field cables. I grabbed one, nipped it with pliers and bared the and with my knife. In a minute it was joined to the end of our own cable. This German wire, I thought, must lead somewhere.

Taking

it as guide I walked up the road, followed by Stone, who nodded

understandingly. About 200 yards ahead, the ditch was bridged over and

at this point the cable was led upwards to a pole.

Taking

it as guide I walked up the road, followed by Stone, who nodded

understandingly. About 200 yards ahead, the ditch was bridged over and

at this point the cable was led upwards to a pole.

The pole stood on the lip of a large chalk quarry which sank from the roadway. We lay beside the pole peering into the deep hollow.

There was no movement in the quarry, which appeared to have been recently abandoned. German clothing and equipment littered the place as if hurriedly discarded. Facing us in the side of the quarry were five doorways leading to what we thought was a big dug-out. Souvenirs running in our minds, we entered the quarry carefully, avoiding noise. We approached the nearest dug-out shaft and furtively peered in the entrance.

I gasped. The shaft was deep and probably not quite completed, as there were no steps, only boards reaching from the ground level downwards, with one or two wooden treads. Leaning against the wall inside the doorway was a German sentry fully equipped. Half-way down another German was seated with his back to the door, crouched on one of the treads.

The sentry gave a queer cry and made to seize his rifle which was propped against the wall opposite him. As he did so he lost his footing and stumbled headlong down the shaft on top of his comrade. Both slithered to the bottom. Instantly a chorus of voices from below was heard in protest.

The situation called for only one remedy - flight. The dug-out had five doors and might be swarming with men. We were without even one Mills bomb. In a twinkling we were speeding down the road, but before we had gone any distance rifle bullets were whistling around us. We jumped in the ditch and crawled laboriously back to the canal bank, where we rejoined our sniper and once more connected the telephone.

The moment the instrument was affixed a loud buzz indicated that someone was calling us. The colonel had come to a company station in the front line accompanied by the brigadier, who wished to speak to Mr. Stone. I retained the headpiece telephone whilst handing him the speaking set.

The

brigadier was a professional soldier of the most efficient type, and I

wondered how heroics of this kind would appeal to him.

The

brigadier was a professional soldier of the most efficient type, and I

wondered how heroics of this kind would appeal to him.

He listened in silence whilst Stone reported the position in the quarry. Stone went so far as to ask for a platoon to be sent out with bombs to capture the dug-outs.

"Stone," said the brigadier, "we've had quite enough damned silliness for one day. Lie low where you are and I'll 'phone Corps to strafe the quarry whilst you make your way back here over the open." Stone acquiesced meekly.

It was now afternoon and Stone considered he deserved another drink. I handed him the rum bottle, and he drained it at a gulp. Shortly afterwards he was asleep.

Telephonic communication must have been in good working order that day. In a very short time the message to the Corps had its effect. Shells of every calibre were whistling over our heads, bursting in and above the quarry. This was the moment arranged for our retreat. I 'phoned to the signaller, back in the front line, that I was disconnecting.

Turning to Stone, I gave him a shake. He was like a log. I shouted and punched, but all to no avail. He would not move. I thought of threatening him with his own Webley. We were compelled to await his awakening. This came with the darkness, and we walked carefully over to our front line praying that the sentries would not mistake us for Germans.

We were challenged, gave the reply, and were once more back in a forward trench, although not with our own battalion, which had been relieved at dusk.

I have told this incident in as simple a way as I can; I feel I owe that to my conscience, because there is a romantic version of it in the London Gazette which does not say one word about rum or revolvers.

Private Alexander Paterson enlisted at Glasgow on October 21st, 1915, at the age of eighteen. Trained at Glasgow, Ripon, and Richmond (Yorks). Went to France, July 1916, and remained with the Glasgow Highlanders in the 100th Infantry Brigade, 33rd Division, until within four weeks of Armistice. Fought on Somme from July 1916 till March 1917. At Arras, April to June 1917, in Ypres Salient, September 1917 till April 1918. Saw severe fighting during retreat in Flanders, April 12th to 17th, 1918. Took part in final offensive operations till wounded near Le Cateau on October 13th, 1918. Was also wounded (slightly) at Delville Wood, on August 22nd, 1916, and gassed (slightly) in October 1917. Received Military Medal in respect of episode dealt with in narrative.

First published in Everyman at War (1930), edited by C. B. Purdom.

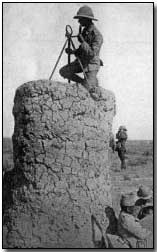

Photographs courtesy of Photos of the Great War website.

An "incendiary shell" is an artillery shell packed with highly flammable material, such as magnesium and phosphorous, intended to start and spread fire when detonated.

- Did you know?