Memoirs & Diaries - War is War - Passchendaele

The

chapters on Passchendaele reinforce everything already said about that awful

initiative. Burrage found both horror and humour.

The

chapters on Passchendaele reinforce everything already said about that awful

initiative. Burrage found both horror and humour.

"A nucleus of about a hundred and twenty men is being left behind as a peg on which to hang a new battalion if we should be completely chewed up. I imagined the married men with the longest families would be on the nucleus, but not a bit of it... There were in my company twin brothers who were only sons. Surely it would have been only fair to keep one of them back... the twin brothers were killed.

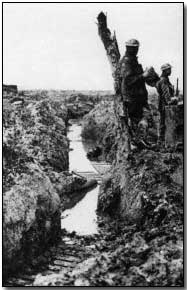

"Dawn reveals to us a sight which nobody could visualize without having actually seen it. We can stand up and see the round of the horizon. It is like being on the sea, but our sea is a sea of mud. There is not a blade of grass nor a spot of colour anywhere. Only the least undulations tend to relieve the monotony of complete flatness. In the middle distance there is something which might by exaggeration be called a 'hill'. We imagine that this must be the celebrated Passchendaele Ridge.

"On occasions when things were not going too well I was always a man of few words. I had no time for bright and airy conversation. I liked to crowd myself into the smallest possible space and have a think.

It was not so with Rumbold. "…ah- would you considah that we are undah fire?" It was his first time in action, and he wanted to write home and tell his mother that he had been under fire, but was conscientious about using this time-honoured phrase before its exact technical meaning had been made clear to him.

I did not at the time understand the psychology which had prompted the question. Since everything around us seemed to be going up in the air and descending again in the form of stones and showers of liquid mud, accompanied by the noises of whining nose-caps and the mosquito-like hum of roving splinters, the question seemed to me to be utterly uncalled-for and in very bad taste. "You stick your bloody fool's head up and you'll bloody soon see," I said. Rumbold subsided quite satisfied. He was under fire.

"We had already seen what had happened to the first 'ripple'. They had all made for that spot of higher and drier ground, and the Germans having retired over it, knew exactly what must happen, and the sky rained shells upon it. Shrapnel was bursting not much more than face high, and the liquid mud from ground shells was going up in clouds and coming down in rain.

The first 'ripple' was blotted out. The dead and wounded were piled on each others' backs, and the second wave, coming up behind and being compelled to cluster like a flock of sheep, were knocked over in their tracks and lay in heaving mounds. The wounded tried to mark their places, so as to be found by stretcher-bearers, by sticking their bayonets into the ground, thus leaving their rifles upright with the butts pointing at the sky. There was a forest of rifles until they were uprooted by shell-bursts or knocked down by bullets like so many skittles.

"The mud which was our enemy was also our friend. But for the mud none of us would have survived. A shell burrowed some way before it exploded and that considerably decreased its killing power.

"Nothing had stood up and lived on the space of ground between ourselves and the pill-box a hundred and fifty yards away. I saw a stretcher-bearer, his face a mask of blood, bending over a living corpse. He shouted to somebody and beckoned, and on the instant he crumpled and fell and went to meet his God. To do the enemy justice, I don't suppose for one moment that he was recognised as a stretcher-bearer.

Another man, obviously off his head, wandered aimlessly for perhaps ninety seconds. Then his tin hat was tossed into the air like a spun coin, and down he went. You could always tell when a man was shot dead. A wounded man always tried to break his own fall. A dead man generally fell forward, his balance tending in that direction, and he bent simultaneously at the knees, waist, neck and ankles.

Several of our men, most of whom had first been wounded, were drowned in the mud and water. One very religious lad with pale blue watery eyes died the most appalling death. He was shot through the lower entrails, tumbled into the water of a deep shell-hole, and drowned by inches while the coldness of the water added further torture to his wound... our C. of E. chaplain - who went over the top with us, the fine chap! - was killed while trying to haul him out.

"...A very old man of nearly forty and a Boer war veteran, had been shot sideways through the seat of the trousers. He was in considerable pain but responded quite happily to badinage. I told him that he couldn't possibly show his honourable scars to his lady friends and that he might find it difficult to convince the pretty nurses that he was facing the right direction when the bullet found him... I hate to report that his wound turned septic and he died very shortly afterwards in a C.C.S." (casualty clearing station)

"D Company was lucky. It had lost only about half its men. I... found a sergeant who was pained because I hadn't shaved. He told me to get into a shell-hole - any one would do - clean my rifle and shoot any one who couldn't properly pronounce the consonant 'W'."

After the attack there were 18 left in his company. "Our Q.M.S., whom I had always found rather military, met us and carried my rifle for me. "You've had a hell of a time," he said with a catch in his voice. "Pretty bad," I agreed, "but it might have been worse."

"Worse!" he gasped. "Yes," I said. "We didn't see any of the bloody Staff." That at least made him laugh. They had rationed for about five times the number of men that actually returned, so for a change I got enough to eat. The Q.M.S. then gave me three-quarters of a mess-tin full of rum - neat, and proof spirit at that. It would have killed a man who didn't really need it. But I drank it and slept like a little child for six hours."

Next - Leave

Photographs courtesy of Photos of the Great War website

A respirator was a gas mask in which air was inhaled through a metal box of chemicals.

- Did you know?