Memoirs & Diaries - A Memoir of Service in the German Army During August 1914

Captain Huebner's

narrative begins with his enthusiastic and patriotic departure for the

front, hints at rapine and drunkenness in Belgium, and continues as follows:

Captain Huebner's

narrative begins with his enthusiastic and patriotic departure for the

front, hints at rapine and drunkenness in Belgium, and continues as follows:

Before reaching Louvain we bivouacked near a large well-built village, and here we had the wettest and merriest evening in the whole campaign.

Some of our battalion water-carriers discovered a wine-cellar in the village. On going into a cellar they noticed a stack of fagots, and guessed that they were put there with a purpose. The fagots were quickly cleared away, and behind them appeared a door.

It led to a cellar filled with thousands of bottles of wine. They loaded themselves inside and out with the precious liquid, so that it is no wonder they walked into camp with unsteady gait.

Louvain, which afterwards attained so sad a fame, received us in quite a friendly manner. The inhabitants put vessels of drinking water in the streets. During a long halt in one of the suburbs they willingly brought us food, drinks, and cigars.

Towards evening we marched past a splendid red sandstone building, the Congo Museum. It is surrounded by a beautiful park, through the trees of which we caught glimpses of the royal palace, Tervueren.

Soon

afterwards we entered the southern suburbs of the Belgian capital. The

streets re-echoed the tramp of thousands of feet and the marching-songs of

the troops. Thousands of the inhabitants lined the street, watching

the endless columns with curiosity and dismay...

Soon

afterwards we entered the southern suburbs of the Belgian capital. The

streets re-echoed the tramp of thousands of feet and the marching-songs of

the troops. Thousands of the inhabitants lined the street, watching

the endless columns with curiosity and dismay...

August 23rd brought us into touch with the hated English.

A report came that about 30,000 English were in position on the other side of the canal, and our two divisions had to attack them.

Our regiment was in reserve in a forest intersected by a railway. As we marched to our position in the forest we could hear the rattle of rifle-fire and the thunder of artillery in the distance. But we were soon ordered forward.

We marched over a railway crossing, and at the quick step along the wide, dusty street of a large village with a burning August sun overhead, while the kindly villagers handed our men supplies of water and fruit.

A short halt was called under the high wall of a park, and there we learned to our great joy that the artillery had successfully bombarded the station at J-, near Mons, thus preventing the detrainment of English troops. In advancing we passed the munition wagons of our heavy artillery, then, taking a path to the left, crossed meadows straight for the village.

A part of it was already in flames, and the rifles were cracking in the park of a large chateau on the right.

Large numbers of wounded were carried past us; they were from the gallant X regiment, which had stormed forward on its own, and, after heavy street fighting, had captured the station and some factories.

We

lay down for a short time while our artillery continued to pour shells into

the village. Cries of jubilation greeted a well-aimed shot which took

away the top of the church-tower with the Belgian flag fluttering on top and

set the tower on fire.

We

lay down for a short time while our artillery continued to pour shells into

the village. Cries of jubilation greeted a well-aimed shot which took

away the top of the church-tower with the Belgian flag fluttering on top and

set the tower on fire.

It was nearly seven o'clock before the English, who had obstinately defended the place, evacuated it and retreated at top speed. They had had their first taste of the furor teutonicus.

Our regiment did not come under fire again that day, but now we rushed forward and crossed the canal by an excellent bridge which our pioneers had erected. On the other side were the ruins of the railway station; a little further on we saw the first English prisoners - a corporal and eight men-sitting with their backs against a wall.

Our men were standing round gazing at the helpless Britons. I must admit that they made an exceedingly good impression - strongly-built, sun-burnt, well-equipped soldiers. I was sorry that I could not speak English, but a one-year volunteer noticed my embarrassment and offered to interpret.

This young soldier then narrated this extraordinary story "I know the second prisoner from the left quite well; he is an old school friend of mine. My parents lived in England for twenty years, and we sat on the same school-bench together. We have met again here, but, it is true, under very different circumstances." The world is indeed small!

The farther we penetrated into the village the traces of the fight became more evident. Large buildings had been literally riddled by the German shells; the rifle bullets had split the red bricks in the houses, and as we turned a street corner there lay before us the first dead Englishman.

In a signalman's cottage we found quite a number of the enemy's dead, for it is said that the British - if it is at all possible - carry the dead as well as the wounded into cover.

It was an industrial village, but the streets were quite deserted. Beyond it the country sloped upwards to various single hills, on the highest of which we could plainly see a huge stone obelisk, topped by a gilded object. We recognized the gigantic granite monument erected by the French in memory of their victory over the Austrians at the battle of Jemappes, 1792.

Our

battalion encamped at the foot of the obelisk. But while the shadows

of evening fell upon the landscape our artillery advanced to pursue the

retreating English with their fire.

Our

battalion encamped at the foot of the obelisk. But while the shadows

of evening fell upon the landscape our artillery advanced to pursue the

retreating English with their fire.

On the left the neighbouring division was still hotly engaged with them. They were only able to force a passage over the canal, which the English had defended with obstinate bravery, and were now endeavouring to drive the enemy out of the factories, woods, colliery-buildings, and villages, in order to come into line with our division.

Across there the fire swelled to one long tremendous roar, then weakened, and after sunset ceased entirely. I shall never forget the scene, nor our own feelings, as we sat around on the monument steps.

We felt a kind of mad joy that at the first set-to the hated English had got some good German blows and been hurled back.

But we were compelled to admit that these English mercenaries - whom many of us before the war had looked down upon with disparagement and contempt - had in every case fought valiantly and tenaciously. This was sufficiently obvious from the heavy losses which our German troops had suffered here.

After a hurried meal from the field-kitchen, we marched on a good distance in the waning light, in spite of the day's exertions. The English, however, had vanished; so the regiment assembled in the long, desolate street of a neighbouring village for a halt. We all sank absolutely exhausted on the cobble-stones, and very soon loud snoring sounded between the long rows of houses.

It was by no means inspiring when an order was brought for us to return and act as a cover for the heavy guns. It seemed as if our superiors were determined that we should be quite pumped out, for the march back through blazing Jemappes to the village of G- was an endless, racking strain.

Our feet and legs almost refused to fulfil their functions; no word was spoken, and we rejoiced when, after two hours, a halt was called.

Towards midnight we arrived at G-, where the heavy artillery had marched up; guards and double sentries were detailed, and we looked for quarters.

After

a long search and much hammering of doors I found excellent quarters for

four of us in the house of a frightened but very obliging schoolmaster.

After I had got to bed the good man brought me a bottle of red wine and some

roast beef which his wife had just prepared.

After

a long search and much hammering of doors I found excellent quarters for

four of us in the house of a frightened but very obliging schoolmaster.

After I had got to bed the good man brought me a bottle of red wine and some

roast beef which his wife had just prepared.

During the whole campaign I have seldom slept so well and comfortably as in the house of these good people.

The first day of the great battle with the English, of which our fight was only a part, was a Sunday. With us Sunday came to be synonymous with Schlachttag (battleday), for nearly every important engagement fell on that day.

On the first day our regiment had not actually gone into action, but what we had missed was more than made good on Monday, August 24th.

First of all we had to cover again the long march of the night before, and while on the road we could hear the roar of battle ahead. Our regiment was allotted the task of driving the English out of the village F-, in which they had employed all sorts of devices to defend the houses.

The village stood on a moderate height before us; on the left it turned back almost at right angles, while on the right a number of factories and collieries stretched down the slope. Open, stubble land rose gently between these two wings to the village.

While our battalion halted behind a huge slag heap, the other two battalions of our regiment were heavily engaged with the enemy. From our covered position we could see the English projectiles exploding with great exactness above our comrades, but they were already pushing forward, and finally our turn came too.

We had hardly swerved into the open when English bullets began to whistle round our heads. We at once advanced in open formation, while a battery came up on the right and, after a short duel, silenced the enemy's guns, but his rifle-fire increased in violence, and we had to cross 1,200 yards of open field.

Here and there one or other of our men sank with a short scream or dragged themselves groaning to the rear. Finally we rushed to a railway bank, across the top of which the enemy's bullets fled through the air like swarms of bees.

But we could not lie there forever; the two first battalions were heavily engaged about 300 yards in advance of the railway, and badly in need of our support. So I yelled the order: Sprung auf, marsch! marsch! (Up and forwards!)

A

veritable hail of bullets greeted us as we rushed over the bank. Then

we advanced by short rushes; throwing ourselves flat after each short rush

we worked our way into the first line.

A

veritable hail of bullets greeted us as we rushed over the bank. Then

we advanced by short rushes; throwing ourselves flat after each short rush

we worked our way into the first line.

While our artillery was hurling shells into the village and into the factories on the right we climbed the height and entered the village from behind. Just as on the previous day, however, the English had completely vanished. They must have run at an extraordinary speed.

We got into the houses through the back gardens and by breaking open doors and windows, for everything was locked and bolted; the English had even put sand-bags against the cellar windows.

In order to get into the street we had to break open the front doors, and I was nearly shot by my own men in the process, for they mistook me for an Englishman trying to escape.

Three of the enemy's wounded were discovered, two of whom were able to walk, but the third had had his shin-bone shattered by a bullet and lay in great pain behind a house. As we put a first dressing on the wound he screamed in agony under our clumsy, inexperienced fingers, but nevertheless he managed to stammer his "thank you".

Thus ended our second day in the great battle of Maubeuge (note: also known as the Battle of Mons), and again we had driven the English out of their fortified positions, although we had to attack across the open.

It is true our losses had been heavy, but so had theirs. We had discovered that the British are brave and doughty opponents, but our Army had inspired in them a tremendous respect for the force of a German attack. Captured English officers said that they had not believed it possible for us to storm across such open country.

Several of our companies had suffered very severe losses through the enemy's artillery fire and the machine guns which the English had very cleverly placed so as to catch our troops in the flank.

There was desperate street and house-to-house fighting, but the same regiment which had met the English the day before succeeded in driving them out at the left side of the village and in making many prisoners.

An incident which I witnessed characterizes the feeling of our soldiers towards the English people. A number of prisoners were being escorted past us when our men shook their clenched fists and rained down curses of the foulest kind on Tommy Atkins, who marched past erect, with his head up and a smile on his face. When, later, French prisoners were brought in, I never observed any similar outbursts of a national hate which is only too well founded.

After

the English had been thrown back along the whole line we bivouacked in an

open place in the village of F-.

After

the English had been thrown back along the whole line we bivouacked in an

open place in the village of F-.

The straw was already spread out, but nothing came of it. We had only a two hours' rest, then started again; after a long march we reached the village of W-, where we found passable sleeping quarters but nothing to eat.

On August 25th a period of tremendous forced marches began, which brought us in a few days across the Marne to the southeast of Paris.

Our armies were close on the heels of the retreating enemy, the purpose of the General Staff being to push him away from Paris and hurl his armies back on to the line of fortresses (Belfort, Verdun, etc.) in the west. Unfortunately the scheme failed, for various reasons which I cannot and may not discuss in this place.

Nevertheless, that hurried rush through Northern France - a rush which called for the most tremendous exertions of both man and horse - will remain forever in my memory. In those pathless forced marches I did succeed, however, in keeping at least a list of the towns and villages which we passed through.

On August 25th our battalion was detailed to cover the light munitions column of the X Field Artillery Regiment, and on the same day we crossed the French frontier at 3.15 p.m. Only a small ditch marked the dividing line between the two countries, and our two companies crossed the little wooden bridge with loud hurrahs.

On the 26th, after a long march, we reached B-, and found decent quarters. The news that two English divisions had been annihilated aroused great enthusiasm; but the fact that I had received no news from my family for twenty-six days considerably damped my share of joy.

Furthermore, in those days of forced marches the food supply was exceedingly irregular. There was no bread to be had, although the field-kitchens worked fairly well. But it was quite impossible for the provision-columns to keep pace with us. I was exceedingly glad to find a large boiled ham in the village shop, and promptly requisitioned it.

On the following day we continued the pursuit of the English. In order to stop our advance they made another stand at Le Cateau, but, in spite of a most gallant defence, received a crushing defeat.

Our regiment did not participate in this fight, but as we marched near to the battlefield, on our way southwards, we found numerous traces of the English retreat. The enemy artillery had left great heaps of their ammunition on both sides of the road, in order to save at least the guns.

For

quite an hour we were marching between these remarkable monuments of German

victories and English defeats, and never have we enjoyed a higher degree of

malicious joy than during that day's march.

For

quite an hour we were marching between these remarkable monuments of German

victories and English defeats, and never have we enjoyed a higher degree of

malicious joy than during that day's march.

The countryside teemed with small parties of English troops who had got cut off from the main body. As it was easy for them to hide in the woods, and as one was never sure of their strength, a lot of valuable time was lost in rounding them up.

One of our cavalry patrols discovered a party of them near the village W-, and our battalion, with my company in front, was detached to clear them out. Very soon we got glimpses of the well-known English caps, and here it must be admitted that in making use of cover and in offering a stubborn defence the English performed wonders.

When we advanced against their first position we were received with rifle-fire, then they vanished, only to pop up in a second position. They were dismounted cavalrymen whose horses were hidden farther back, and, after decoying us to their third line, they mounted and fled.

Between two of their trenches we found the dead horses of a patrol of Uhlans which they had apparently ambushed.

After a very fatiguing march we reached the townlet of B- about 7 p.m., and were lucky to find some excellent beer in an inn by the market-place. Of course the place was packed with thirsty soldiers; the hostess and her daughter did splendid business that evening.

August 28th was another day of tremendous exertion. Our course led at some distance past St. Quentin, and this day brought our first fight with the French.

During the ensuing march to find our regiment again, we were amazed on entering a village to see the inhabitants welcoming us with shouts and other signs of jubilation. T hey had mistaken us for English, and it was exceedingly funny to see the transformation in their faces, and how quickly they disappeared into the houses, when they discovered their mistake.

I have forgotten where we slept after the terrible fighting and marching exertions of that day; but in my diary is the short notice: "Disgusting quarters."

Next

morning, by 7.30, we had reached the Somme. Our men were gradually

getting accustomed to this race across France.

Next

morning, by 7.30, we had reached the Somme. Our men were gradually

getting accustomed to this race across France.

The number of those who dropped out decreased from day to day; the feet got hardened, but our bodies, it is true, got thinner. It is noteworthy that on these tremendous marches one suffered comparatively little from hunger.

A swede or turnip from the next field, some chocolate, a cigarette, or a cigar, was often sufficient for a whole day. cFurther, the exultation of having defeated the enemy helped us to endure anything...

September 1st, the anniversary of Sedan, was just as beautiful a day as forty-four years before. We crossed the Aisne in the early morning by Vic, and crossed a wide stretch of open country to a plateau in the hilly forest district of Villers Cotterets.

At the edge of this plateau we could hear our guns in front bombarding the village V-, and soon afterwards we heard heavy infantry fire - a sure sign that we were close to the enemy. As a matter of fact, our brigade-regiment was heavily engaged with the English rear guard.

Unfortunately, we only came up in time to congratulate our comrades on their splendid success.

A forest fight is always a difficult affair, but the woods in France claim particularly heavy sacrifices, because the French allow the undergrowth to grow very thick. This forms a great obstacle to an advance, and at the same time affords the defender great advantages.

The English had chosen a height commanding a turning in the road which led through this huge forest, and spent several days in strengthening the position. Yet our gallant brigade-regiment, in a fight of a few hours, had hurled them back and inflicted heavy losses on them.

When the last shots had echoed through the magnificent forest, several companies of our regiment were ordered to accompany the Field Artillery through the forest. At intervals of ten steps we marched by the side of the guns in case of a surprise attack.

As we passed the scene of the fight which was just ended we met numbers of our stretcher-bearers and small groups of captured British. At the top of the height in the forest we saw a large number of the enemy's killed and seriously wounded.

Apparently

the fight had raged hottest at the turn in the road, for just there the dead

and wounded lay thick around, some 900 in all, in comparison to which our

losses had been relatively light...

Apparently

the fight had raged hottest at the turn in the road, for just there the dead

and wounded lay thick around, some 900 in all, in comparison to which our

losses had been relatively light...

The strain and exertion which we endured on September 3rd were almost beyond human capacity. From 6 a.m. till 10 p.m. we tramped along the dusty roads under a hot September sun, with only a couple of hours' rest at noon, till we reached the neighbourhood of the Marne.

Towards evening several hostile airmen circled above us at a great height.

At S-, in the Marne valley, we found passable quarters, and, after the terrific efforts of the day, sank exhausted into a deep sleep. Still these terrible marches did not bring us to the desired goal; we could not overtake the retreating enemy, and it was said that the French and English were marching to the southeast, towards Italy.

On Friday, September 4th, we crossed the Marne at 7.30 a.m. in beautiful autumn weather. But this delightful day was to be impressed on our memories by another tremendous march.

We passed through the district where Blucher had been well thrashed by Napoleon a hundred years ago, and crossed the Morin (a tributary of the Marne) in the vicinity of Montmirail, reaching our quarters in the village, M-, just as darkness fell.

Several officers, including myself, were in a miller's house at the exit of the village. A strong barricade of ploughs, wagons, etc., was erected, and a strong guard paced about 100 yards down the road.

We had not slept long when we were roused by heavy rifle fire. The guards had seen a troop of soldiers marching towards them in the moonlight and opened fire.

Our companies were alarmed and awaited an attack which never came. The sentries asserted that they had shot a number of the enemy, and, as a matter of fact, we found several dead and wounded by the roadside, among them a French colonel.

The other companies in the village had also made some captures, among then being Turcos and some Zouaves, with their unpractical, theatrical uniforms. From the prisoners we learned that the English and French Armies, defeated at St. Quentin and Maubeuge, had fallen into great confusion.

Portions

of these armies had completely lost themselves and were wandering about

aimlessly between the German columns advancing to the south.

Portions

of these armies had completely lost themselves and were wandering about

aimlessly between the German columns advancing to the south.

Again and again they collided with German troops on the right or left, till at last they did not know which way to turn.

The enemy, therefore, was more exhausted and suffering more than we were; added to this we were the victors, a fact which enabled us to endure all the demands put upon our energies.

It is true that we suffered greatly in those days from want of food. In my diary is the remark: "Nothing to eat for three days; abjectly wretched."

Source: Source Records of the Great War, Vol. II, ed. Charles F. Horne, National Alumni 1923

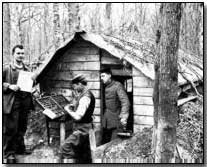

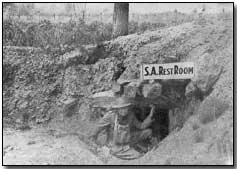

Photographs courtesy of Photos of the Great War website.

"Boche" was a disparaging term used to describe anything German.

- Did you know?