Memoirs & Diaries - Messines, October 1918

It was a cold wet day

towards the end of September 1918, and we had pulled our guns out from our

position on Pilckem Ridge from which we had been firing on Passchendaele.

It was a cold wet day

towards the end of September 1918, and we had pulled our guns out from our

position on Pilckem Ridge from which we had been firing on Passchendaele.

We were resting in an old school at Hazebroucke while our O.C. had been finding a new "possy" for our guns. I had been with this particular battery about five months, having come out from Prees Heath as a reinforcement the previous April.

"Jerry" had presented me with a cushy "Blighty" at Ypres in November 1917, and coming back to the same part of the line after five months in England did not make me feel very comfortable. In fact I was "windy," more so than at any time during my first spell of fifteen months in France.

Day after day we had had casualties: a few killed, some wounded, others gassed. When was I going to get mine ? I wondered how it would come. Would half my body be pitched up into the branches of a tree as had been the case with one poor gunner on the canal bank?

I hoped not, please God, not that! Nor like that boy who got it in the stomach at Reninghelst, who, when we let down his trousers, found his intestines bursting through the two holes the shell fragments had made. I prayed that I should not be mutilated.

If I had to go "West," let

it be a quick death - a hole in the head perhaps; that wouldn't be so bad. But let my body be in one, and not scattered, when they came to bury me.

If I had to go "West," let

it be a quick death - a hole in the head perhaps; that wouldn't be so bad. But let my body be in one, and not scattered, when they came to bury me.

There was one man in this battery who gave me comfort. His name was Bob Lawrence. He was a bombardier and the No.1 of our gun. He and another gunner, Frank Thomas, were my particular chums. The others of our gun detachment who formed our clique were Jimmy Fooks, the oldest man in our section, whose time was nearly up: he was looking forward to going home soon for a month's leave; Harris, a fair-haired youth, who had just come back from leave and had left a young bride behind; and Kempton, who was due for leave and expecting to go any day.

Bombardier Bob Lawrence was a butcher in civil life. He was very easy-going and good-tempered, and never appeared to have the wind up. He was slow in his movements - a plodder. Nothing upset him: shells didn't worry him - at least he didn't show it if they did. He floundered about in the mud as if he enjoyed it, but the lice played hell with him.

He would spend an hour cleaning up his shirt, killing the vermin until his thumb nails were covered with their blood. As soon as he put his shirt on, he would start itching again and scratch himself raw. He was quite bald, without eyebrows, or eyelashes; his body was as hairless as a baby's.

He used to wear a wig of a dirty ginger colour which was beginning to show signs of wear, so that at the artificial parting you could see the soiled leather or rubber that formed its foundation.

At this time Bob had been

in France three years, and I thought he was safe for "duration".

At this time Bob had been

in France three years, and I thought he was safe for "duration".

He had never been hit, and I thought he never would be. If I was one of a working party sent to prepare a forward position or build an observation post, I was nervy and "windy" if Bob was not of the party.

I would start off with my limbs trembling and my heart in my mouth, and, until we were well on our way back to billets, I would be nothing but a bundle of nerves. Indeed, it was only by exercising all my will power that I was able to hide my feelings and control my actions.

If Bob was with us, how different I felt! "It's all right; nothing to worry about," and off I would go contented and almost care-free.

We had made a fire in an old oil drum which was planted in the middle of the class-room of the school that was our temporary home at Hazebroucke. The room was full of smoke, and this made our eyes water and rendered the atmosphere so thick that one could cut it.

About thirty men were lying about, some reading, some writing letters, others having a "crumb up," as we called the process of picking lice from our shirts. Steel helmets, gas respirators and the remainder of our equipment were hanging from nails in the walls, and sand-bags filled with spare clothing and private property acted as pillows.

Harris had been giving us an account of his leave, telling us what it was like sleeping between sheets again and taking his meals off a clean tablecloth. He told us, too, how a flapper had presented him with a white feather one day when he was out in "civvies" with his wife.

Then we started talking of our chances of coming through the War. We had all seen over twelve months' fighting, and had overlived our allotted span of life as R.G.A. gunners. Bob, with his three years of active service, had become quite a fatalist.

"It's no use worrying,

Ken," he said, turning to me. "If a shell has got your name written on it,

it will get you; it will turn round corners to get you." Then he started

singing in his fiat, cracked voice, "What's the use of worrying, it never

was worth while," until someone suggested a game of nap.

"It's no use worrying,

Ken," he said, turning to me. "If a shell has got your name written on it,

it will get you; it will turn round corners to get you." Then he started

singing in his fiat, cracked voice, "What's the use of worrying, it never

was worth while," until someone suggested a game of nap.

Bob couldn't resist a game of nap. He would go "nap" with the most impossible of hands, and I am afraid he was "rooked" shamefully. He would lose all his pay the very day that he received it; but he never went short of anything as long as one or the other of us had it.

Parcels from home, cigarettes, tobacco, tooth-paste, shaving soap, and writing paper were property common to our little clique. If you wanted something that one of the others had, you just helped yourself in front of his eyes. If he wasn't about, you helped yourself just the same, and told him, if you thought of it, when he returned.

You would curse and swear at each other to the best of your ability, but never with any bad feeling. If your chum came back to billets too drunk to stand, you would just put him to bed, tuck his blankets around him, and put an empty biscuit or fruit tin near his head in case he should need it.

Then you would turn in beside him, and cuddle up to him for warmth, and share his lice with him. In the morning you would fetch his breakfast of bread and bacon and canteen of tea to him in bed, as he would probably awake with a thick head.

Bob always slept with a Balaclava helmet on his head. In fact his head was always covered, and I believe he was rather conscious of his wig. When I think of it, it amazes me that we didn't pull his leg about his wig, but we never did.

It wasn't that his stripe protected him, as we chaffed him as much as we did each other. We often told him to "go to hell" or to take a "running jump at himself." He would then threaten to run us in for "insubordination"; that was his favourite saying, but never once did he report any man.

Though he was an N.C.O., he

always did his share, and often more than his share, of all the hard and

disagreeable tasks that fell to our lot, such as humping 6-inch shells and

boxes of cartridges weighing over 1 cwt.

Though he was an N.C.O., he

always did his share, and often more than his share, of all the hard and

disagreeable tasks that fell to our lot, such as humping 6-inch shells and

boxes of cartridges weighing over 1 cwt.

If the caterpillars had to be fixed to the wheels of the gun on a dark, shell-swept road covered with thick slimy mud, Bob would do his whack, getting his hands all bashed and cut, and his fingers pinched between the blocks.

On duty at the battery, though there was no need to for him to do a turn on guard, he always would, so that each man's turn might be a little less. He wouldn't even choose his turn, but always took his chance out of the hat as we gunners did.

Perhaps we would have to do a harassing fire during the night at the rate of ten rounds per hour on roads behind the enemy's line. Then Bob would split his detachment into two, working the gun with four men and himself, while the other four got what sleep they could in the dug-out.

When the night was half through he would send his four men in and call the other four out, but he would stick to the gun throughout the night, with no rest at all.

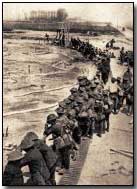

On October 2nd about twenty of us were sent forward over Messines Ridge to prepare positions for two guns that were coming up during the night. A lorry took us as far as safety would allow; then we made our way on foot along a road up the Ridge.

The Germans had this road under observation, so we went along in parties of three and four, 50 yards or so separating each party. A day or so previously this road had been held by the enemy and now the bodies of Germans and horses lay about, the stench from which was fearful.

Some were headless, some

limbless, while others looked just asleep.

Some were headless, some

limbless, while others looked just asleep.

A German gun team had been caught by one of our shells as it was getting away. Two of the horses lay dead in the traces, two gunners in grey lay in the road, while a third was doubled across the muzzle of the gun, all dead. One of the wheels was smashed, and under the gun was a hole in the road where the shell had burst.

In charge of our party was Sergeant Ellis, D.C.M., and we passed the spot on the left-hand side of the road where he had gained his medal by getting three of our guns away and blowing up the fourth as the Germans came over the Ridge when they attacked in the previous March. The remains of the blown-up gun were still there.

Running along the right-hand side of the road was a bank about 2 feet high, from which the ground sloped away to flat country below. Bob Lawrence, Frank Thomas, and myself were trudging along together in tin-hats, gas masks at the "alert," and loaded up with picks, shovels, petrol tins of drinking water, and rations.

Suddenly there was a "Phee-ew, crash! Phee-ew, crash! Phee-ew crash!" and three 4.2's burst about 20 yards to the left of us. We dashed to the side of the road and cowered beneath the 2-foot bank while Hell opened its gates and poured a storm of fire, gas, and flying jagged pieces of steel on the road: 77-mm. shells coming with a "whizz-bang!"

4.2's coming with a sighing moan and a crash, and big 5.9's with their "Phee-ew-ew!" rising to a crescendo and culminating in a roar like that of an express rushing through a station. On top of the bank were the bodies of two Jerries, and these gave us a little more protection, for we could hear the "Phut! Phut!" as flying pieces of red-hot steel found a billet in them.

We endured this torment for about ten minutes or a quarter of an hour, though it seemed ages. During this time Bob didn't turn a hair, though he didn't speak a word. Neither did I. All my energy was directed towards making myself as inconspicuous as possible!

The shelling stopped at

last, and continued 200 yards further along the road.

The shelling stopped at

last, and continued 200 yards further along the road.

The only remark Bob made was, "Bit hot while it lasted, Ken, blast 'em." Then we made off as fast as we could down a side road to the left into a bit of a hollow.

Here was a pillbox of concrete, together with a big signpost bearing the word "Last-Kraftwagen," and it was near here, on the side of a narrow road, underneath a few scarred trees that we had to prepare our gun positions.

We called this position "Last strafed wagon" because of the signpost. Away to our left front, about two or three kilos. away, rose the spire of a church which we were told was Wervicq and held by the enemy. We were ordered to lie low and do nothing till dusk, as we were visible to any observation that might be carried out from that spire.

About 100 yards or so to the rear of our gun position was a little shelter of rotting sand-bags filled with earth, and this we made our cook-house. Here we gathered and hid ourselves till dusk, when we made some tea, after which we started work on our gun-pits.

We levelled the ground and made a platform of railway sleepers. The other section did the same a little distance down the road.

Just after midnight we heard the rumble and clatter of lorries and guns coming down the road, and in a couple of hours we had both guns in position and camouflaged, and the shells, cartridges, and fuse boxes, etc., all stored around the guns.

The major, who had come up with the guns, told us we should be relieved at ten o'clock in the morning. Then he went away, leaving another officer in charge. As there was no shelter against shell fire, Sergeant Ellis ordered us to dig a fire-trench to the rear of our gun, big enough to accommodate ten or a dozen men.

This we proceeded to do and by daylight had dug a trench about 4 yards long by 1 yard wide and about 5 feet deep, our intention being to cover it over later and make it into a dug-out.

About eight o'clock in the

morning we went across to the cook-house for breakfast, which consisted of

tea, bully beef, and biscuits. There was a heavy ground mist, so we could

move about without fear of being observed from Wervicq.

About eight o'clock in the

morning we went across to the cook-house for breakfast, which consisted of

tea, bully beef, and biscuits. There was a heavy ground mist, so we could

move about without fear of being observed from Wervicq.

After breakfast we went back to our trench to await our relief. Sergeant Ellis went into the gun-pit under the tarpaulin to get a little sleep while the rest of us squatted in our trench talking. Ten o'clock came and the mist was rising, but no relief!

10.30 and no relief. Eleven o'clock and we were getting very impatient and angry, but still no sign of the relieving party. We were tired out. It had rained during the night, we were wet and cold and covered in mud; our eyes smarted and our feet felt like clay. We were grimy and lousy, and our cigarettes were all gone; we had descended to the depths of misery.

We were afraid to walk about in case we were spotted from the spire at Wervicq. Presently Frank Thomas said to me, "What about going across to the cook-house, Ken, to see if there is any tea?"

"Too much fag," I replied. A quarter of an hour later something came over me, and I turned to Thomas and said, "Come on, Frank, let us go now. Come on, Bob," but Bob wouldn't come, so we promised to bring him some tea back if there was any.

So Thomas and myself scrambled out of the trench and, keeping the scarred trees between us and the church spire, we made our way to the cook-house, only to find biscuits, but no tea. We munched a few biscuits and begged a cigarette from our temporary cook, and warmed ourselves by the dying embers of his fire.

We had been there about ten minutes when Thomas suggested that we should go back to the trench, but I was in no hurry. If the relief came up we wouldn't have so far to go from where we were. Just then we heard someone shouting "Is that --th Battery?" and, looking around, we saw it was one of our officers who had brought the relief along.

He

sent Thomas and myself to tell Sergeant Ellis that the relief had arrived.

He

sent Thomas and myself to tell Sergeant Ellis that the relief had arrived.

We were half-way back to the trench when suddenly there were four or five explosions, following quickly one on another. We flung ourselves flat on our faces and heard the "Whirr-phut! Phut! Phut!" as fragments of steel flew around.

I was scared stiff, and a cold sweat came over me. Bob wasn't there to give me the comfort of his presence. We lay there a few minutes waiting; then there was another salvo of shells and, peeping up, I saw a cloud of black smoke and a fountain of earth rise in the air over the trench where Bob and the others were.

We waited a little while, but, as nothing else came over, we made a dash towards the trench.

God! what a sight met our eyes! A shell had landed right among the boys. It was a slaughterhouse - just a mass of mangled flesh and blood. Bob's head was hanging off; you could only recognize it by his poor, worn-out, dirty little wig.

Jimmy Fooks was squatting on his haunches, not a mark on him, quite dead, killed by the concussion. You couldn't tell which was Harris and which was Kempton - what was left of them was in pieces. I was numbed. I felt as if a great weight was pressing on my head. I was choking.

In a dream I heard the sergeant's voice, "For God's sake get away. Get to hell out of it before they start again."

He had been asleep in the gun-pit and was untouched. Somehow I got back to the lorry which was waiting to take us back. Then I broke down and between my sobs I cursed the Germans. Though I had always felt I could not kill a man, at that moment I could have killed with my bare hands the Boche gunner who had fired that shell.

We knew the enemy was beaten; we knew it couldn't last much longer, and at this time, after three years in France and the end so near, Bob must be killed! Harris, who had left a young bride in England - killed! Jimmy Fooks, whose time was nearly up - killed! And Kempton, who was due for leave - killed also!

Why hadn't they come across

to the cook-house with Thomas and me? Why hadn't the relief come up to time?

If either of these things had happened Bob would still be alive.

Why hadn't they come across

to the cook-house with Thomas and me? Why hadn't the relief come up to time?

If either of these things had happened Bob would still be alive.

And then I remembered his fatalism - "It's no use worrying, Ken. If a shell has got your name on it it win get you; it will turn round comers to get you," and it had done that to Bob and the others; it had found its way into that trench and got them.

They left them where they fell and covered them over. The trench which they dug to give them shelter in life proved to be their grave, and sheltered their bodies in death.

Gunner A. B. Kenway joined Glamorgan R.G.A. (Territorial) November 1915. Age twenty. 2/3rd Coy. Went to France, September 1916, with 172nd Siege Battery. First time in action at Vimy Ridge, then at Hebuterne from October to December 1916.

Battle of Arras (April 1917.) Third Battle of Ypres (July 1917). Battery position: on Canal bank. Later, position near the China Wall, not far from Hell Fire Corner, to the right of the Menin road. Was burned there, but stayed a few days with battery, but, as it was ordered to Italy, had to go into hospital.

Sent to Mile End Military Hospital, London November 1917. April 1918, back in France as reinforcement, posted to 155th Siege Battery, which was in action near Reninghelst, in the Ypres area; later at Barre, near Hazebroucke. From there to Pilckem Ridge; later to Gapaarde near Messines (scene of narrative).

Then to Dottignies, a hamlet near Tourcoing, until the Armistice. Demobilized January 26th, 1919. Resumed civil occupation February 2nd, 1919, as a ledger clerk.

First published in Everyman at War (1930), edited by C. B. Purdom.

Photographs courtesy of Photos of the Great War website.

Prevalent dysentery among Allied soldiers in Gallipoli came to be referred to as "the Gallipoli gallop".

- Did you know?