Feature Articles - Mountain Fury

Mid May 1916

Mid May 1916

the Italian soldiers in the Trentino were aware that something serious was

about to happen in their sector. High Command was showing an unusual

degree of interest in a region that was supposed to be a bit of a backwater

– all of a sudden there was a frantic drive to bolster the defence lines.

Since when, many men asked, had there been so much bother over the second and third lines? Surely the Austro-Hungarians had a screw loose if they were proposing to fight it out on territory that in many places was more favourable to herding mountain goats?

The answer to the last question came on May 14 when a bombardment was unleashed on Italian positions. On the next day men expecting to be on the edges of the action suddenly found themselves grappling with an attacking enemy at close quarters.

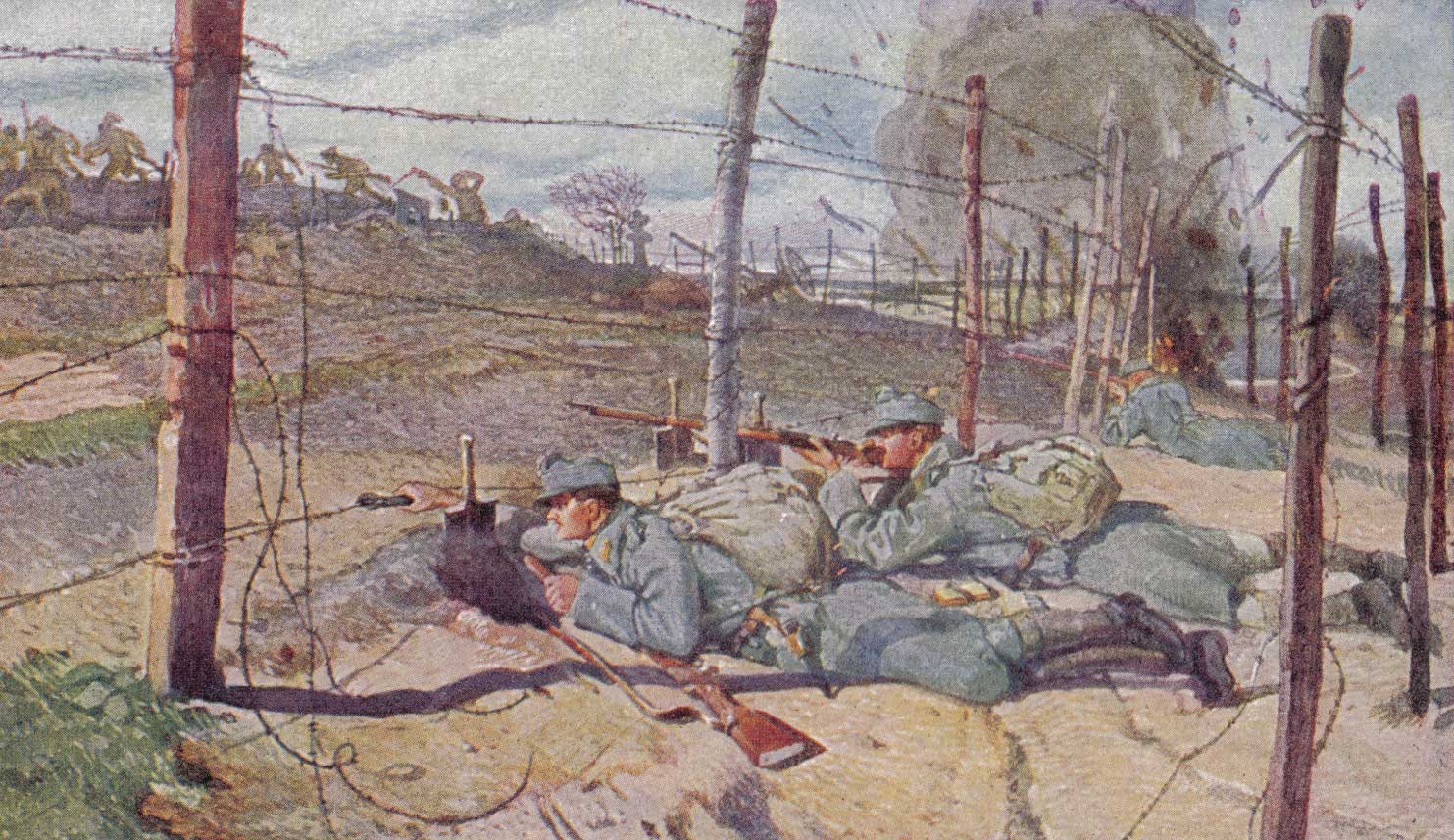

Scrambling across the harsh terrain, hordes of pike-grey uniformed infantry pressed forward as the canons continued to find other targets to pummel, while the rattle of machine guns and the crack of grenades rent the air. Expecting their opponents to flee, the Austrians found the Italians were prepared instead to fight to the last man. And so began the one of the bloodiest campaigns ever to be fought in the Alps...

The Grand Plan

Since summer 1915, when Italy dramatically

entered the war on the Entente's side, Italian armies had been nibbling

and biting away at Austro-Hungarian territory, particularly in the

Isonzo region

of the north east.

Since summer 1915, when Italy dramatically

entered the war on the Entente's side, Italian armies had been nibbling

and biting away at Austro-Hungarian territory, particularly in the

Isonzo region

of the north east.

Here they had been creeping inexorably towards their ultimate goal, the Trieste region. Although the cost so far had been high, the Italians stubbornly persisted in battering away at her enemy's defences in the firm belief that the edifice would soon collapse, leaving Italy victorious and able to reunite the Italian-speaking regions of Austro-Hungary with the motherland.

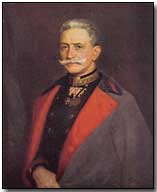

Feeling the growing pressure from the Italian Front, Austria was becoming keener than ever to pluck the Italian thorn from its side so as to be free to concentrate on fighting its main enemy, Russia. The great question, though, was how this goal could be achieved. By winter 1915, Austria's Supreme Commander, Conrad von Hotzendorf, believed he had found the solution.

Together with his Supreme Command, Conrad

decided the Austro-Hungarian army would launch a grand sweep down from the

Trentino mountain region and on into the Venetian Plain.

Together with his Supreme Command, Conrad

decided the Austro-Hungarian army would launch a grand sweep down from the

Trentino mountain region and on into the Venetian Plain.

Surprise and swift movement would be needed, along with superiority in numbers. Logistical difficulties would be immense, but these, Conrad believed, were surmountable.

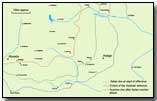

The actual fighting in the mountain zone, if events went according to plan, was only to be a fraction of the campaign. Once the men had pushed along the roughly 50 mile (80km) front from the Adige Valley to the Sette Comuni Plateau and on to the Val Sugnana. They would then push through to Thiene, Bassano and Vicenza. Once out into the lowlands, the Austro-Hungarian army would cut off the Italian army on the Isonzo Front from the rest of Italy and their enemy's surrender would then become nothing more than a formality.

But to make the Trentino campaign work, Austro-Hungary would have to denude the Galician Front of her best men and material; yet if the Russians unleashed a well-directed offensive at the same time as the fighting raged in Italy, then major damage could be caused. However, if German manpower was bought on board for the Trentino offensive, then Austria could leave a sizeable number of divisions in the East as a safeguard. After Italy was crushed, Austro-Hungarian troops would then be free to be transported quickly back east to combat Russia and other opponents.

Gathering Storm

Conrad asked for help from his German

counterpart,

Erich von Falkenhayn – preferably in the shape of nine top-quality

German divisions, with accompanying artillery.

Conrad asked for help from his German

counterpart,

Erich von Falkenhayn – preferably in the shape of nine top-quality

German divisions, with accompanying artillery.

Falkenhayn, however, thought Conrad's plan left to much too chance: too much depended on things going right, without much consideration for the usual mix-ups, breakdowns and misjudgements that occur in battle and down the supply chain.

Falkenhayn also considered Conrad's proposed use of 18 Divisions as too small in number – 25 would be much better. Not that Falkenhayn, despite his personal misgivings, could have been much help anyway: the Germans were about to wade into what would become the bloodtub of the Verdun offensive and he would needed all the men he had at his disposal.

Conrad, while disappointed with Germany's negative response, was not dejected enough to pack up his plans. Indeed the rejection may well have spurred him on – if Germany would not help, then Austria would 'deliver the goods' alone and against the odds.

Conrad moved 13 divisions away from the Eastern Front and combined them with forces in the Trentino region to produce two armies – the 11th, under General Dankl, and the 3rd, under General Kövess von Köessháza. The armies were placed one in front of the other and would act in tandem to give greater penetration power.

At the sharp end 157,000 men had been

gathered for the fight and had 1977 guns to support them. Overall,

however, 400,000 men including vital supply and logistic units would take

part in Austria's offensive in some way or another. Of the artillery,

476 guns were of heavy calibre, including three 420mm monsters, some of the

most powerful artillery pieces then in existence.

At the sharp end 157,000 men had been

gathered for the fight and had 1977 guns to support them. Overall,

however, 400,000 men including vital supply and logistic units would take

part in Austria's offensive in some way or another. Of the artillery,

476 guns were of heavy calibre, including three 420mm monsters, some of the

most powerful artillery pieces then in existence.

In command at ground level was Archduke Eugen, while one of the corps was placed in the hands of Archduke Karl Franz Josef, the future (and last) Emperor of Austro-Hungary.

The Austrians were quick to get down to detailed planning – solving the communications and logistics difficulties of mountain warfare were, of course, the major keys to the success of the whole operation. Joint planning between commanders in the field, however, was going to be difficult and in some cases nigh on impossible. At many points it would be left up to them to use their best judgement as events unfolded. It was hoped that the (perceived) lack of Italian morale and willingness to fight would make the job of attacking easier.

If the Austrians kept to their timetable an acceptable level of communications could be re-established once the mountain barriers were passed. More of a headache for the logisticians was the question of food and water. During the war, the Italians came to the conclusion that a soldier needed 3,900 calories a day to perform in combat conditions on the middle ranges. As for the Austrians, trying to feed 157,000 men roughly 3,900 calories a day over mountains was going to be immensely difficult and again in places impossible. Once the offensive began, a number of units were expected to have to rely on iron rations for days at a time.

Caught Napping?

Many Austro-Hungarian and German

historians, and even a number of academics from Allied nations, have liked

to present the Italians not just surprised by the Trentino offensive, but

almost dumbfounded by its audacity and initial force.

Many Austro-Hungarian and German

historians, and even a number of academics from Allied nations, have liked

to present the Italians not just surprised by the Trentino offensive, but

almost dumbfounded by its audacity and initial force.

In reality, the Italians, while not best prepared defensively, had certainly taken measures to bolster their resistance and were well aware that Austria had intended to make some kind of advance in the theatre, although they did indeed misjudge its scale.

Early on, General Cadorna was convinced, as were the other key strategists in the Allied nations, that Austria would not risk withdrawing forces from the Russian Front to begin an offensive in Italy. Thus he settled down to making plans for a new Italian offensive on the Isonzo Front (there had been five there already) and reiterated to General Brusati, in command of the 1st Army and in charge of the Trentino sector, to remain on the defensive. Cadorna did send some reinforcements, although they were small in number.

For the Italians it was most unfortunate then that General Brusati liberally interpreted his orders: a 'thrusting' general he liked to maintain an offensive stance. Instead of defence in depth, the front line remained almost the sole centre of his attention. Advance posts were pushed out as far as feasibly possible and plans continued to be made for small-scale actions to re-jig the line in Italy's favour.

The second and third defence lines – the

vital jump-back points giving an army the ability to bend in defence when

facing a furious assault – were not well-enough developed. The fourth

and final line existed, according to Cadorna, merely as a coloured marking

on a map.

The second and third defence lines – the

vital jump-back points giving an army the ability to bend in defence when

facing a furious assault – were not well-enough developed. The fourth

and final line existed, according to Cadorna, merely as a coloured marking

on a map.

Adding to the dangerous nature of things, Brusati had placed his dumps of material and many artillery units up at the front end. It was a policy that played with fire: if the enemy launched an overwhelming attack, Italian forces risked being swamped. If the first line was broken, the Austrians would then be able to advance with greater ease as the bulk of the opposition would have been liquidated.

By early spring 1916 intelligence unequivocally pointed to an offensive in the Trentino by Austria (although Cadorna still underestimated the scale). Consequently, the Supreme Commander visited the region to examine the state of defence. What he saw did not please him.

Moving his headquarters to the area in April, Cadorna issued immediate orders to strengthen the defence lines. Advance points or positions that did not favour defence were re-aligned or abandoned. More reinforcements were rushed up – 67 additional battalions and 20 batteries arrived, while the 9th and 10th Divisions were placed directly behind 1st Army in a supporting role. Brusati was dismissed, with General Pecori-Giraldi taking his place.

It was still hoped that the offensive

would not be large enough to disrupt Cadorna's Isonzo plans and it is here

that the Italian General was somewhat neglectful. Had more men been

sent up to the defence lines then Austria's Trentino offensive may well have

fizzled out a lot earlier than it actually did.

It was still hoped that the offensive

would not be large enough to disrupt Cadorna's Isonzo plans and it is here

that the Italian General was somewhat neglectful. Had more men been

sent up to the defence lines then Austria's Trentino offensive may well have

fizzled out a lot earlier than it actually did.

As it was, the Italians still only had 118 battalions at the front, with 40 in reserve, supported by 623 guns (of which many were already antiquated). Morale in the Italian forces, however, was fairly good – despite the infantryman's miserable pay, poor conditions and almost complete lack of furlough.

Mountain Thunder

With their armies in place, the Austrians

were admirably prepared – supply dumps had been bought forward and detailed

plans disseminated down the command chain.

With their armies in place, the Austrians

were admirably prepared – supply dumps had been bought forward and detailed

plans disseminated down the command chain.

For the average soldier the campaign was presented in propaganda terms as a punishment expedition against the Italians for breaking her alliance with the central powers and then joining the Entente and making the surprise attack of 1915.

The prospect of food, plunder and booty once the Austro-Hungarians broke out of the mountain ranges was also alluded to. Some historians have noted that tourist guides were also supplied to a number of officers in the field – a case, perhaps, of invading Italy, seeing the sights and then eating at the best restaurants!

The Austrians were well aware that in mountain war it was absolutely vital to secure the flanks. It was no good taking vast chunks out of the centre only to then face deadly harassing fire and counter attacks from the surrounding heights and mountains. Therefore the flanks of the theatre were to be attacked and secured first before unleashing the major assault on the centre.

Somewhat optimistically, Conrad believed

his campaign could start in April, giving Austria more time to destroy Italy

and then return troops to the East. The weather, however, was too poor

and so the offensive was postponed for a number of weeks.

Somewhat optimistically, Conrad believed

his campaign could start in April, giving Austria more time to destroy Italy

and then return troops to the East. The weather, however, was too poor

and so the offensive was postponed for a number of weeks.

On 14 May the Austrians started a short and extremely sharp bombardment. The following day the battle for the flanks began: in the west the Austrian drive started between Val Lagarina and Val d'Astico and in the Northeast, the attempt to force through the Val Sugana was initiated. In the West, the men of the Italian 37th Division were rushed by the Austrians and forced to scrabble back to Col Santo (2,115m/6,930ft). With grit and determination the Italians held on tenaciously before falling back again on the 18th.

German General A von Cramon recorded the Austrian opening moves as 'magnificent'. Even the American Ambassador to Italy at this time, Thomas Nelson Page, had nothing but praise in his account of the action. He wrote:

The Austrians knew every foot of ground: mountain and valley, and their attack was admirably planned and well carried out. Both Artillery and Infantry were skilfully handled.

In the next breath he added:

The Italian advanced positions were swept away by the flood of shell poured out on them.

Although the start had been spectacular there

were niggling points of worry for the Austrians – the Italians, while being

forced back, were not cracking. Indeed, they were putting up spirited

resistance. Speed, which was essential to Austro-Hungarian success,

was also being sapped.

Although the start had been spectacular there

were niggling points of worry for the Austrians – the Italians, while being

forced back, were not cracking. Indeed, they were putting up spirited

resistance. Speed, which was essential to Austro-Hungarian success,

was also being sapped.

The attack was held up on the principal lines of resistance at Coni Zugna and Passo di Duole. From 23 to 28 May it was the scene of constant combat, the last day seeing a whole Austro-Hungarian division thrown at the enemy on a single point of resistance initially defended by one battalion from the Italian 62 Infantry.

Today, looking at the scenery it seems incredible that such actions could have taken place and on such a large scale. Woods intermingled with bare rock faces: much of the topography is uninviting to all except the experienced hiker. Having to fight over this landscape – a great deal of it at hand-to-hand quarters – must have pushed many men to the very limit.

The Italians soon reinforced the beleaguered defenders with five other battalions. By 30 May, the Italians despite inflicting heavy losses had been bled white. Ten officers and 148 men were dead, 28 officers and 583 men were wounded and 152 were listed as missing – a total of 911 casualties noted in all. Taking this kind of loss while maintaining the position was impossible, and so the Italians were forced to withdraw yet again. With covering protection from a force of Alpini (special troops especially raised for mountain war) they were able to do this in order and set up new line of resistance at M. Cogolo-Novengo.

The Gloves Come Off

In the northeast in the Val Sugana region

the Austrian advance started well, pushing aside Italian advance posts with

ease. But again, the going became tougher with the more progress made.

At some points the Italians even made audacious counter-attacks. At

Monte Collo (1,825m/5,985ft), for example, the Ionio Brigade held its ground

then launched a localised assault, doing much to put their opponents facing

them on the wrong foot.

In the northeast in the Val Sugana region

the Austrian advance started well, pushing aside Italian advance posts with

ease. But again, the going became tougher with the more progress made.

At some points the Italians even made audacious counter-attacks. At

Monte Collo (1,825m/5,985ft), for example, the Ionio Brigade held its ground

then launched a localised assault, doing much to put their opponents facing

them on the wrong foot.

Although pleased with the staunch defence their troops were putting up in the area, Italian Command made the sensible decision to have the line drawn back to the torrent Maso, bringing a greater degree of uniformity to the Front and easing the supply situation. Meanwhile, the Austrians resumed the offensive and from the 25th to the 26th fought and took possession of M. Civaron, but faltered in taking Monte Cima e Monte Ravetta.

Away from these actions, fighting on the Folgaria plain started on the same day as the assaults on the flanks. Here the Austrian corps under Archduke Karl advanced against the Monte Maronia-So d' Aspio line and eventually drove the Italians back to the third line on the Novegno group, south of Arsiero, and almost the last alpine barrier before reaching the foothills and down into the Vicenza plain. With success tantalisingly close for the Austrians, the Italians knew they had to hold firm. The soldiers in the field were well aware that defeat in this location could well be catastrophic for the country.

Action in the centre on the Asiago Plain

began with a massed bombardment on 15 May as the assaults on the flanks

began. The shelling was on a scale unprecedented for the Italian

Front. Salvos pummelled the opposition – their blast effect made

doubly deadly as the rocky ground they exploded on sent up showers of lethal

shrapnel. The firestorm lasted until 20 May when the main drive began.

Action in the centre on the Asiago Plain

began with a massed bombardment on 15 May as the assaults on the flanks

began. The shelling was on a scale unprecedented for the Italian

Front. Salvos pummelled the opposition – their blast effect made

doubly deadly as the rocky ground they exploded on sent up showers of lethal

shrapnel. The firestorm lasted until 20 May when the main drive began.

In the very thick of the action, the Italian Palermo and Ivrea Brigades held on stubbornly, but outnumbered and outgunned they were eventually dislodged and fell back to the next line of resistance.

The speed at which the Austrians were attacking and their success at bringing up their artillery compromised this position and the Italians were soon retreating to the last marginal line of defence, but here too they held on to the death as instructed by supreme command.

The Austrians now found themselves in the position they had done much in trying to avoid. The Italian flanks had in the main held quite well, while in the centre – although ground had been gained – the Italians had not caved in as dramatically as had been expected. This made the central position (the Austrians were now in control of the best part of the Sette Communi plateau and the upper portion of the Brenta valley) a restricted place to manoeuvre in. One Italian commentator after the war wrote:

On this tableland of the Asiago…[Austrian] battalions and artillery [were] all but smothered by their advance.

But this assessment is, perhaps, a little

over-optimistic, for at this point in the campaign Italy was still very much

in danger and reinforcements were desperately needed if the enemy was to be

held from gaining a second wind and advancing further.

But this assessment is, perhaps, a little

over-optimistic, for at this point in the campaign Italy was still very much

in danger and reinforcements were desperately needed if the enemy was to be

held from gaining a second wind and advancing further.

Enemy at the Gates

Fortunately for Italy, General Cadorna was making immediate efforts to get men and material into place. Despite his many flaws as a commander, Cadorna was an excellent logistician. On 21 May he issued an order announcing the creation of a new army – the 5th.

Formed up in the plains, it was composed of five corps and a cavalry division (about 400,000 men). For three whole days Northern Italy's railway infrastructure was devoted to ensuring the 5th Army was created. It is a testament to Italy that such a vast feat was accomplished in such a short period of time. Meanwhile, reinforcements that were closer to hand – 93 battalions and artillery units – were rushed to the front.

Knowing that the Italians would be mustering their reserves to halt their advance, the Austrians redoubled their efforts. On 25th May they attacked Monte Cimone, north of Arsiero and drove back two Alpini battalions and forced the Italians into realigning their front. Ominously for the Austrians, however, the first of their units had to be siphoned off back to the Eastern Front as early as 27 May (the threat of a Russian offensive was now imminent). The Austrians were also facing major difficulties with their logistics, while the Italian supply inversely improved the closer they fell back on the inner line.

By 2 June the Italians, although still on

the defensive, felt that the corner had been turned. Austrian assaults

seemed to lack the vigour of the first attacks. If he could gather

enough reinforcements on the front within a short space of time, Cadorna

believed he could deliver a devastating counter offensive. Attacking

the Austrian flanks he could swing his forces around the enemy, leaving the

enemy army trapped and weakened in a pocket, before delivering the coup de

grace.

By 2 June the Italians, although still on

the defensive, felt that the corner had been turned. Austrian assaults

seemed to lack the vigour of the first attacks. If he could gather

enough reinforcements on the front within a short space of time, Cadorna

believed he could deliver a devastating counter offensive. Attacking

the Austrian flanks he could swing his forces around the enemy, leaving the

enemy army trapped and weakened in a pocket, before delivering the coup de

grace.

In the meantime, Cadorna got on with bolstering the men's morale – the fighting was still fierce and the danger, especially if their resolve failed, remained acute. On 3 June he issued an order declaring:

Remember that here we defend the soil of our country and the honour of army. These positions are to be defended to death.

On 4 June the Russians launched their offensive and the next day marked the high tide of Austria's effort in the Trentino.

After this, men and material were sent back east in earnest – indeed, on 5 June itself a whole division left the offensive zone. The momentum was slipping away from Austro-Hungary and now building up on the Italian's side.

The Fight Back

Italy's counter-offensive started on June

14th. Cadorna and his High Command's logistic skills were paying

dividends and the Italians now had a chance to punish the enemy. On 16

June the main drive began with four Italian corps charging into the fray,

pushing the flanks back as planned. A day later, Austrian High Command

ordered the suspension of offensive operations in the region.

Italy's counter-offensive started on June

14th. Cadorna and his High Command's logistic skills were paying

dividends and the Italians now had a chance to punish the enemy. On 16

June the main drive began with four Italian corps charging into the fray,

pushing the flanks back as planned. A day later, Austrian High Command

ordered the suspension of offensive operations in the region.

The Italians now started to drive the Austro-Hungarians back along all parts of the front. By 25 June Austrian High Command bit the bullet and ordered their units to fall back to a pre-prepared defence line that was ahead of their old positions, but not by much. On the same day, the Italians retook Asiago. What was once a pretty Italian mountain community was now a pile of rubble. Julian Price, a war correspondent was on hand to record the scene:

The spectacle was but a repetition of what I had seen on the Western Front; heaps of rubble and smouldering ruin on all sides.

Cadorna now had a choice to make: should he continue battling away at the Austrian's new defence line or return his attention to the Isonzo front? Both regions contained heavy defences, but given its topography the Austrian Trentino would be a spectacularly difficult region to fight in. And if the Austrians had proven one thing with their offensive then it was that large scale fighting in the middle ranges was extremely difficult.

That said, Cadorna did have momentum on his

side and may have held the opportunity to inflict further defeats on an

emaciated opposition.

That said, Cadorna did have momentum on his

side and may have held the opportunity to inflict further defeats on an

emaciated opposition.

After some deliberation, he chose to return Italy's efforts back on to the Isonzo front. Meanwhile offensive action, although on a smaller scale, continued in the Trentino.

With the danger in the Trentino passing, the Italian public and politicians, searching for a scapegoat for what was publicly perceived as a near disaster and quickly chose to vent their frustration on the government, which collapsed with the forced resignation of the premier Salandra. In its place a new national government was created, which in the long term was a benefit to Italy's war effort.

Butcher's Bill

Trentino had been bloodbath: the Italians lost 15,000 killed and 76,000 wounded. About 56,000 men were taken as prisoners and 294 guns had been lost (although most had been put out of action as withdrawals took place). The Austrians recorded 10,000 dead, 45,000 wounded and 26,000 taken prisoner, although many statisticians believe her losses may well have been larger.

As Falkenhayn had predicted, the Austrians had bitten off more than they could chew. With only 18 divisions they could not maintain the weight of their offensive once Italian resistance stiffened. Had fresh men been available for a final push the last mountain barrier may well have tumbled. But even then, Cadorna's organisation of the new 5th Army meant that the Austrians would then have had to face a second gruelling battle – one that in probability would have ground their advance to a halt.

As it was, the Russian offensive – the one Conrad prayed to be delayed – put the biggest spanner in the works for Austria's ability to even retain the limited gains she had made in the first place, particularly on the Asiago plateau. With large numbers of men having to be siphoned off for defence of the east, this territory – a small one, but a gain none-the-less – was impossible to hold.

Both sides learned much from the offensive and from the development in mountain warfare in the middle ranges in general. But perhaps the largest lesson learnt was proof that a grand offensive, or a large counter attack, in these climes was seriously hobbled by the terrain, the logistical difficulties and the high casualties inevitably taken.

Men fighting from rock face to rock face, up and

down steep gradients and at high altitudes also tired quickly. Without

a constant flow of fresh forces to throw into the maelstrom, the maintenance

momentum – absolutely vital in the offensive – became impossible.

Men fighting from rock face to rock face, up and

down steep gradients and at high altitudes also tired quickly. Without

a constant flow of fresh forces to throw into the maelstrom, the maintenance

momentum – absolutely vital in the offensive – became impossible.

Dangerously, the Italian High Command while noting the above, did not in any appreciable way feel the need to explore in depth the defensive mistakes it had made that helped facilitate much of Austria's early successes. While Brusati must take the blame for pushing his troops, supplies and guns to the very front only to face being overwhelmed, his stance was not an unusual one and was mirrored by Italian commands across the Front.

Even after Trentino, the notion of having strong defence lines to retire to in case of disaster was not one readily adopted by the Italians. This was to have dire consequences later in the battle of Caporetto 1917, where Austria – together with Germany this time – implemented a crushing defeat similar (although it was ultimately unsuccessful) in vision to the one Conrad had conceived back in the winter of 1915.

Select Bibliography

Books

Alberti, Italian Military Action in the World War, Hugh Rees, 1923

Caracciolo, Italy and the World War, Edizioni Roma, 1936

Evans M M, Forgotten Battlefronts of the First World War, Sutton Publishing, 2003

Jung P, The Austro-Hungarian Forces in World War I (1), Osprey, 2003

Jung P, The Austro-Hungarian Forces in World War I (2), Osprey, 2003

Nicolle D, The Italian Army of World War I, Osprey, 2003

Page T N, Italy and the World War, Charles Scribner’s sons, 1920

Villari L, The War on the Italian Front, Cobden Sanderson, 1932

Willmott H P, First World War, Dorling Kindersley, 2003

Internet Sources

Barzini L, The Battle in the Snows

Davini F, The North-western Austro-Italian Alpine Front – A General Overview

First World War.com

Ortner C, Austro-Hungarian Formations During World War 1

Powell E A, Fighting on the Roof of Europe

US Army, Nutritional Advice for Military Operations in a High-Altitude Environment

Warren W, Climbing the Snow-capped Alpian Peaks

Wilson C, Asiago – 1916 Two Views

The 'Guerra Bianca in Adamello' Museum 1915-1918

Battle Police were military policemen deployed behind an attack to intercept stragglers.

- Did you know?