Feature Articles - Munich

Munich, 21 February, 1919: The

young Count Anton Arco auf Valley had tried earlier that day, but the crowds on

Promenadestrasse, the street leading between Bavaria's Foreign Ministry and

Landtag, had blocked his line of sight. With the morning rush now abating,

he felt more confident of success. Standing a little way from the Foreign

Ministry doorway, he knew that it was now just a question of waiting...

Munich, 21 February, 1919: The

young Count Anton Arco auf Valley had tried earlier that day, but the crowds on

Promenadestrasse, the street leading between Bavaria's Foreign Ministry and

Landtag, had blocked his line of sight. With the morning rush now abating,

he felt more confident of success. Standing a little way from the Foreign

Ministry doorway, he knew that it was now just a question of waiting...

Inside his offices within the Foreign Ministry, a bearded man in his fifties - a pince-nez carefully balanced on the end of his nose - put the finishing touches to a speech. Resembling a ruffled librarian, Kurt Eisner, the Premier of the Free Republic of Bavaria was preparing to hand over power; the speech he was working on was a resignation proclamation to be delivered in the Bavarian Landtag just after 10.00am that day.

Eisner made a farewell address to his colleagues and then dismissed his secretarial staff for the last time. With his two aides, Fredrich Fechenbach and Benno Merkle, and two guards, he prepared to set off to the Landtag.

Fechenbach voiced his concern for Eisner's safety. The Prime Minister was now so despised by the people of Munich that it would be dangerous, he said, for them to take the normal route. "They can only shoot me dead once," said Eisner, brushing Fechenbach's fears aside.

The two guards came out of the doorway first, followed by the other three men. Eisner walked in the middle. Turning on to Promenadestrasse, they passed the innocuous-looking young man without a second glance...

The moment Arco had been waiting for had arrived. He raced up behind the

Prime Minister drew up his pistol and fired twice at point-blank range.

The first shot obliterated Eisner's skull, killing him instantly. The

second entered one of his lungs.

The moment Arco had been waiting for had arrived. He raced up behind the

Prime Minister drew up his pistol and fired twice at point-blank range.

The first shot obliterated Eisner's skull, killing him instantly. The

second entered one of his lungs.

The deed complete Arco turned to run - he had only managed a few paces when a bullet fired by one of the guards sent him sprawling to the ground. As he lay writhing on the pavement, four more shots were blasted into him.

Angry crowds rushed to the scene and began baying for the assassin's blood. Fechenbach somehow managed to have the assassin dragged to the Foreign Ministry. From here Arco was taken to hospital, where his life was saved.

As soon as Eisner's mangled body was removed, workers and radical soldiers crowded around the assassination spot. While he was alive, these people had vented their disgust with the Prime Minister; now, in death, they declared him a working-class hero. Weeping, a number of women dabbed their handkerchiefs into Eisner's drying blood.

Astute commentators realised that the pent-up rage of defeat, starvation, racial hatred and class animosity were about to be unleashed. The stage was set for Bavaria's once proud capital to become the hotbed of revolution, the home of Red Terror and the scene of the Freikorps' most dreadful crimes.

Before The Suffering

The Kingdom of Bavaria existed as a sovereign entity long before the notion of a

unified Germany was even mooted in intellectual circles. Until their

downfall, Bavaria's ruling dynasty was the Wittelsbach family - for just over

750 years this family had governed, built palaces and theatres, and courted some

of Europe's greatest artists and philosophers.

The Kingdom of Bavaria existed as a sovereign entity long before the notion of a

unified Germany was even mooted in intellectual circles. Until their

downfall, Bavaria's ruling dynasty was the Wittelsbach family - for just over

750 years this family had governed, built palaces and theatres, and courted some

of Europe's greatest artists and philosophers.

Bavaria had been conducting its own diplomacy with foreign powers for hundreds of years. Its army had a long and proud history, as did many other Bavarian State institutions. Most Bavarians, while content to be members of the German Reich, were wary of Prussia and its dominant position.

In simple terms, most Bavarians saw their northerly Protestant neighbours as slightly arrogant, somewhat bombastic and certainly dull. Catholic Bavaria (over 70% of the state's population looked to Rome for its religious guidance), on the other hand, was seen by its citizens as sensibly conservative, light-hearted and easy-going.

When the new German Reich was created and Wilhelm I declared Kaiser in the Hall

of Mirrors at Versailles in 1871, the Bavarians had already managed to gain a

number of key concessions - called 'reserved rights' - in return for their

joining the new Empire. Bavaria kept her own diplomatic corps and her Army

remained independent and only fell under the Kaiser's control once war was

declared.

When the new German Reich was created and Wilhelm I declared Kaiser in the Hall

of Mirrors at Versailles in 1871, the Bavarians had already managed to gain a

number of key concessions - called 'reserved rights' - in return for their

joining the new Empire. Bavaria kept her own diplomatic corps and her Army

remained independent and only fell under the Kaiser's control once war was

declared.

Bavaria also retained control over her lines of communication and her transport infrastructure. The reserved rights helped maintain a sense of 'difference' that was still evident even by 1914, although the unease Bavaria's population felt about Prussian dominance had faded as the considerable benefits of unification became apparent.

The Golden Age

Bavaria before the War had entered an unprecedented period of growth, both demographically and economically. Munich's population of 230,000 in 1880 had exploded to 596,000 by 1910. Factories were built and tramlines were installed. The very beginnings of what we today would recognise as modern urban and suburban zones were created and expanded upon during this time.

The Luitpold Regency era - named after the benevolent and much-loved Prince Regent Luitpold who ruled from 1886-1912 on behalf of Ludwig II's successor, the mad Otto - became something of a 'golden age'.

Luitpold died in 1912 at the extremely venerable age of 91. His oldest

son, Ludwig, aged a sprightly 67, succeeded him.

Luitpold died in 1912 at the extremely venerable age of 91. His oldest

son, Ludwig, aged a sprightly 67, succeeded him.

Unfortunately, Ludwig was not much of a regal character. Rather than concerning himself with pomp and circumstance - a thing most Bavarians loved about their Royal family - Ludwig was passionate about technology, science and agriculture.

He shied away from visiting the theatre and was rarely seen at large-scale public ceremonies. He was also a usurper.

Upon becoming regent he announced his intention to become king. He managed to do this primarily by securing the support of the centralist Catholic parties and Otto promptly lost his title. While most Munich citizens had no major love for the mad king, they thought Ludwig's decision badly judged at best, or at worst, an example straight from the pages of Machievelli's The Prince.

But despite the controversy surrounding Ludwig's ascension, by 1913 many in

Germany and Europe believed that while the industrious the North and West led

the country economically, it was the South (with Munich at its heart) that led

the country culturally.

But despite the controversy surrounding Ludwig's ascension, by 1913 many in

Germany and Europe believed that while the industrious the North and West led

the country economically, it was the South (with Munich at its heart) that led

the country culturally.

The Seeds Of Conflict

However, to paint Munich in the decades leading up to the First World War as an enlightened city with little to no social tensions other than Royal intrigues would be considerably off the mark.

Life for thousands of Munich's citizens during the Luitpold Regency, and the first years of Ludwig III's reign, was neither joyful nor prosperous - it was a time of grinding poverty. During this period, Bavaria's first city was undergoing an industrial revolution and experiencing a great deal of social upheaval and social deprivation.

The population explosion was brought about because country folk (their jobs more

and more displaced by mechanisation) and poor East European immigrants began

flooding into Munich looking for work and housing. And while there was

work, it was mostly low-paid and menial.

The population explosion was brought about because country folk (their jobs more

and more displaced by mechanisation) and poor East European immigrants began

flooding into Munich looking for work and housing. And while there was

work, it was mostly low-paid and menial.

Those who earned higher amounts were either undercut and forced into accepting lower pay, or were simply laid off. With no welfare state to call on, many unfortunate families found themselves permanently living on the brink of destitution.

The influx of people also created a serious housing problem. Tenement blocks were built to battle the space shortage. 'Flats' were usually one or two room affairs, with children forced to sleep on the floor. Slum barons compounded the misery and misfortune by periodically raising the rents, forcing families out onto the streets.

Those living on the breadline (many were forced into prostitution to make ends meet) began to look for a scapegoat for their woes. The Jewish community despite numbering a mere 8,700 by the end of the 19th Century became the target of choice.

Beerhall Politics

From folk singers to established newspapers, from university professors to

street side orators - all delivered diatribes against the Jews and in a less

media savvy age the message was one that thousands, even in the middle and upper

classes, accepted at face value.

From folk singers to established newspapers, from university professors to

street side orators - all delivered diatribes against the Jews and in a less

media savvy age the message was one that thousands, even in the middle and upper

classes, accepted at face value.

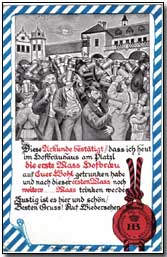

The anti-Semitic message went down particularly well in the boisterous beerhalls. These famous drinking 'palaces' served as a place to debate and, once the arguments were made and more beer had been drunk, a place to fight using beer steins as a weapons.

With so many tensions, it comes as no surprise that socialism and, to an extent Marxism, developed (although the class conflict was diluted to some extent because of the rabid anti-Semitism). As the factories and working conditions became worse, the power of these nascent political forces grew.

The largest socialist party, the SPD, had made great headway in the years leading up to WWI, with a burgeoning membership. At a national level, by 1914 they had become Germany's largest party - although this guaranteed nothing in terms of real 'clout', as power was firmly in the hands of the Kaiser and the army.

In Bavaria as a whole, the largest party was the centre power of the Catholic Party. With the state still very much a rural one, there was little to no chance that the socialists who dominated Munich's politics (their strong Bohemian element also made them more radical than their Berlin counterparts) could ever obtain a democratic mandate in the near future.

Only a terrible, earth-shattering blow to Germany's hierarchy and society would be enough to force change.

Towards The Brink

In the heady days of summer 1914, when war was about to be declared, most in

Munich were enthralled by the vision of a short, but titanic struggle that would

culminate in Germany obtaining European supremacy and taking its rightful 'place

in the sun'.

In the heady days of summer 1914, when war was about to be declared, most in

Munich were enthralled by the vision of a short, but titanic struggle that would

culminate in Germany obtaining European supremacy and taking its rightful 'place

in the sun'.

With many historical and cultural ties to Hapsburg Austria, Bavaria was also supportive of their southern neighbour's desire to punish Serbia and her natural ally Russia. Bavaria's well-documented dislike of the 'easterners' meant most people in Munich thought that a bloody nose for the Slavs was long overdue.

'Russians' - usually unsuspecting east Europeans - were promptly set upon and beaten up. For good measure the crowds also destroyed shops suspected of being controlled by the French or the British, and beat up anyone thought to come from, or sympathise with, the Allied nations.

Once declared, Germany, including Bavaria, welcomed the war: it seemed that for the first time in its splintered history the German people had united to fight a common cause under one leadership. A new national spirit - the Volksgemeinshaft - was felt most deeply in the ranks of the Kaiser's army.

Perhaps Ernst Jünger in his war memoirs Storm of Steel got the closest in capturing this fledgling spirit of unity in words. He wrote: "We were enraptured by war. We had set out in a rain of flowers, in a drunken atmosphere of blood and roses. Surely the war had to supply us with what we wanted; the great, the overwhelming, the hallowed experience."

In the trenches and billets, men from all parts of the country and from all sections of the class spectrum mingled together and worked together in a way that would had been unimaginable in normal times. It was also a factor that explains much of the ex-soldier's fury towards the post-war administrations in Munich who played the separatist card so willingly.

But this was in the future, for now the men marched through Munich to the front and the city cheered.

The Line Wavers

At the close of 1914, Germany had much to feel proud about. Russia's

armies had received a savaging at the hands of

Hindenburg and

Ludendorff.

On the Western Front, the vast majority of Germans believed that the French and

the British had only succeeded in bringing about a temporary stalemate.

At the close of 1914, Germany had much to feel proud about. Russia's

armies had received a savaging at the hands of

Hindenburg and

Ludendorff.

On the Western Front, the vast majority of Germans believed that the French and

the British had only succeeded in bringing about a temporary stalemate.

Once winter was over, most in Germany believed that its main campaign in 1915 would either tip the war in the West to her considerable favour, or, if fortunate enough, win the war outright. While the casualty ratio had given many a shock, almost all Germans remained stoical - the struggle would be soon won and those who had fallen honoured.

When no clear-cut victory materialised in 1915 (all that was obtained seemed to be mounting casualty lists), acts of dissension began to materialise, especially in Munich. In the early war years, however, the disobedience was relatively minor - visiting a city bar or an expensive restaurant, or (if the censor passed it) a play that was deemed inappropriate by the conservative press were examples of this. In Bavaria there was also a growing feeling that the state was shouldering more than its far share of sacrifice in men and material.

There were also fissures starting to show in the business world. Munich's developing industrial base was time and again over-looked when large armament contracts were handed out by the national government. It favoured the industrial north and the Ruhr, which meant that Munich was losing out on vital material and money. Small businesses, starved of the necessary resources struggled to stay afloat, while many others simply folded.

The middle classes began to blame Bavaria's ruling elite and by 1917 the anger had grown to such an extent that Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria lodged a complaint with Berlin. Talking of the middle classes who were finding their livelihoods under threat Rupprecht declared: "The members of this class, who were previously very monarchically minded, are now in part more anti-monarchical than the Social Democrats because they blame the government for their misfortune."

His comments were extremely prescient - when the time came this large demographic portion of Munich's population were among the happiest to see the backs of the Wittelsbachs.

Next - A Sinking Ship

'minnie' was a term used to describe the German trench mortar minnenwerfer (another such term was Moaning Minnie).

- Did you know?