Feature Articles - Uttermost Ends

The people who came home from the First

World War are mostly dead now. It is becoming an event like Waterloo,

the Land Wars or the sinking of the Titanic, a communally preserved nexus of

the two poles of history, memory and forgetting. It is becoming a

history which is part cliché (the mud, the slaughter), part ennobling ideal

(war literature as writing for peace) and part self revelation (New

Zealand's "birth of a nation").

The people who came home from the First

World War are mostly dead now. It is becoming an event like Waterloo,

the Land Wars or the sinking of the Titanic, a communally preserved nexus of

the two poles of history, memory and forgetting. It is becoming a

history which is part cliché (the mud, the slaughter), part ennobling ideal

(war literature as writing for peace) and part self revelation (New

Zealand's "birth of a nation").

As the old but hardly contemptible Great War veteran Albert Tatlock was replaced in Coronation Street by the World War II vintage Percy Sugden, so we are replacing the unspoken memories of the first large industrial war. Memory is being elided by history.

The war marks the New Zealand landscape. Amongst the giant carrots, outsize trout and hyper-real soft drink bottles there are arches, obelisks, halls and museums which were raised for memory. They are all around us but we are forgetting why they are there. Like the missing of the battles whose resting places "are known unto God", the purpose and meaning of them is an absence.

The missing are the subject of this essay. They are named on stone, plastic, paper and the electrical charges of microchips and databases. Their experiences are remembered in the very language - "Over the Top", "trench warfare" - and it's interesting to consider some of these ways of naming.

More exactly, I have taken one person and followed the traces left in public records by him. This is the realm of communal memory as opposed to letters, diaries or yellowing photographs carefully stored by relatives in some suburban lounge china cabinet. That is the province of the personal.

The place to begin is where they ended, the battlefields on the other side of the world. Take a long and exhausting plane trip with its indignities of indifferent food, cramped spaces and surly attendants. Arrive at London and take a train from Victoria Station with its massive monuments by Charles Jagger and go to the coast.

Catch a high speed ferry with its piped Euro music and microwaved convenience foods and noisy packs of teenagers and get to Boulogne. Stand beneath the statue of Napoleon and reflect that this is where most of the troops who went to France had their first taste of vin ordinaire, estaminets and mademoiselles.

They spent some time in training at the notoriously brutal "Bullring" camp at Etaples. It was here that many New Zealand troops came to despise the class ridden absurdities of the British army. They were moved to the front in railway trucks with the famous inscription of "40 hommes et 8 chevaux en long". There was never enough room for everyone to lie down or sit. The resonance of these train journeys was echoed 25 years later by millions on their way to other industrialised killing grounds.

Now we drive in air conditioned comfort with a stereo playing along the hyper ways through green fields. This being France, we drive very quickly indeed and before long we arrive at Albert.

This is a small town in the Department of Picardie which

was the hub of the

Battle of the Somme in 1916.

This is a small town in the Department of Picardie which

was the hub of the

Battle of the Somme in 1916.

It is a bland little place dominated by its famous basilica with its gilded statue of the Virgin presenting a chubby baby Christ. Before the war it was planned to be a pilgrimage site to rival Lourdes. Now it is a pilgrimage site again but no one comes looking for quick fix miracles.

The pilgrims started arriving in 1919 to find the graves of brothers, sons, lovers, fathers and also sisters, mothers and daughters. Along with the excellent regional cuisine, the Great War is the bastion of the local tourism industry which was nicely anticipated by Philip Johnstone in his poem of 1918, High Wood.

High Wood

Ladies and gentlemen, this is High Wood,

Called by the French, Bois de Fourneaux,

The famous spot which in Nineteen-Sixteen,

July, August and September was the scene

Of long and bitterly contested strife,

By reason of its High commanding site.

Observe the effect of shell-fire in the trees

Standing and fallen; here is wire; this trench

For months inhabited, twelve times changed hands;

(They soon fall in), used later as a grave.

It has been said on good authority

That in the fighting for this patch of wood

Were killed somewhere above eight thousand men,

Of whom the greater part were buried here,

This mound on which you stand being ...

Madame, please,You are requested kindly not to touch

Or take away the Company's property

As souvenirs; you'll find we have on sale

A large variety, all guaranteed.

As I was saying, all is as it was,

This is an unknown British officer,

The tunic having lately rotted off.

Please follow me - this way ...

the path, sir, please,

The ground which was secured at great expense

The Company keeps absolutely untouched,

And in that dug-out (genuine) we provide

Refreshments at a reasonable rate.

You are requested not to leave about

Paper, or ginger-beer bottles, or orange-peel,

There are waste-paper baskets at the gate.

The

first day of the Somme, July 1, has bequeathed one of the most enduring

images of mass warfare in the industrial age: long lines of men walking into

machine gun fire.

The

first day of the Somme, July 1, has bequeathed one of the most enduring

images of mass warfare in the industrial age: long lines of men walking into

machine gun fire.

One person who did this on the 15th of September was Jocelyn Clark of the New Zealand Rifle Brigade. He died that day somewhere in front of the village of Flers. His name is recorded with over 1200 others on the Caterpillar Valley Memorial at Longueval which is a small hamlet a few kilometres from Albert.

The New Zealand Memorial is set to one side of the Caterpillar Valley Cemetery. It is a screen wall with eleven panels of Portland Stone. On these are engraved in alphabetical order over twelve hundred names of "...men of New Zealand who fell in the battles of the Somme, September and October, 1916 and whose graves are known only to God" as the inscription runs. These are the missing.

Missing in this case means that they were known to have died but have no grave. They may have been struck by a shell and simply ceased to have any tangible remains. They may have sunk into the chalky, glutinous mud that is characteristic of the region.

They may have been buried on the battlefield but the constant shelling destroyed their remains. These are truly scattered bodies but the only trumpets that sound for them are during ANZAC day ceremonies on the other side of the world.

The War Graves Commission maintains the cemetery and memorial in perpetuity which is a long time indeed. This body grew out of the work of Fabian Ware during the Great War. He was 45 in 1914 and enlisted as the commander of the Mobile Unit, British Red Cross Society. He began noting the names of the dead and the positions of their graves.

There was no official army policy for this which had led to much public distress after the South African War. Mindful of the need to mobilise public support for the first mass war of populations, the British Government was quick to accede official status to Ware's efforts. The unit was officially established on 2nd March 1915.

Now it maintains 2,500 cemeteries and 200 memorials around the world from both wars. It is funded by the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, South Africa, India and New Zealand (whose contribution is 2.10% of the funds) and it is the largest single act of commemoration in history.

The sites are maintained impeccably. Jocelyn Clark's name is easily read amongst the others on the Portland stone panels. Directly across from the memorial stands the Cross of Sacrifice. Carefully designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield in 1918, it is a stone cross with a symbolic bronze sword attached to its face.

A fusion of the military and the sacred which was careful to avoid internecine strife, at least among the Christians, although there was some debate about whether it was in the Anglican or the Catholic tradition.

As for the non-Christians who answered the Empire's call, the India Office raised the question of the Muslim disapproval of exhumation and preference for cremation. Then the Sikhs and Ghurkhas also wanted separate monuments so in the end a single monument for all the Indians who fell in France was settled on.

Chinese characters were carefully inscribed on the graves of those from the Chinese Labour Battalions and in general care was taken to show respect for different creeds.

The crosses stand in all the cemeteries. They are impressive symbols of the brand of muscular Christianity that was a part of the ethos that led to events such as the Somme. This ethos is often evoked in the popular conception of the War in films, TV shows and novels.

It's usually portrayed as a mixture of Victorian circumspection, Imperial arrogance, religious hypocrisy, class subjugation and sexist self-righteousness. Any competent costume drama director can signal all this before the first ad break as it seems to be part of the way we think about the last century. This hardly does justice to the richness and complexity of any age but constitutes part of our communal imaginings.

The implicit nostalgia in these popular histories for a world where everyone knew their place and certitude reigned (pace "Dover Beach") connects straight into a kind of idyllic pastoralism associated with the clichéd summer of 1914 where the Old world was finally wrecked on the reefs of modernism. Philip Larkin as a modern day dyspeptic exponent of this has it in his poem "MCMXIV"

Never such innocence,

Never before or since,

As changed itself to past

Without a word - the men

Leaving the gardens tidy,The thousands of marriages

Lasting a little while longer:

Never such innocence again.

This is one more version of the myth of the Golden Age which is in some ways the religious version of an "atheistic" myth of Progress. We should be thankful, as we are told so often, to be living in a "post-modernist" age where such ideas are now shattered and juxtaposed and then "ironically" re-appropriated via sitcoms and soap operas.

I don't know any of Jocelyn Clark's reasons for enlistment. I don't know how he felt and thought about his experiences. I can find out some things about him but I have nothing he left of himself. He is missing.

At the entrance to the Caterpillar Valley Cemetery there is a small niche which contains a loose leaf folder for visitor's comments and a Register. These grey covered books are found at every memorial and cemetery maintained by the War Graves Commission. They list particulars of all the people the sites commemorate.

The Caterpillar Valley Memorial Register is No. 11. It contains a map of the area and an account of the battles fought there by the New Zealand Division. Jocelyn Cark is on page 17.

We find that his army number is 25/738. He was a rifleman in "A" company, 3rd Battalion, 3rd (Rifle) Brigade. He was killed in action at Flers 15 Sept 1916 aged 26. He was from Maramarua.

The registers of the Commission are another form of memorial in themselves. They are found in libraries and museums around the world. Their sombre volumes are not accorded the reverence that the cenotaphs, obelisks and archways receive but in one way they fulfil the same function. They are mainly looked at by the "granny hunting" genealogists who pore over lists of names in one attempt at personalising history.

If you follow a country road about 2 kilometres from this Cemetery, past one of the roadside crucifixes which became one of the clichés of the Western Front "miraculously unmarked by shells", you arrive at the New Zealand National Memorial.

It's a white obelisk standing in the fields between High Wood and Delville Wood, both scenes of literally unspeakable things. This is the antithesis of personalised memory. On its base is inscribed "From the uttermost ends of the Earth" and it makes you think of home and the war memorials you find in just about every New Zealand town. Put some poppies at its base and drive away. It's time to return.

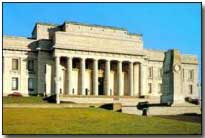

On the Parnell side of the Auckland War Memorial Museum

is carved the name Flers which is part of a ring of names around the

building's exterior.

On the Parnell side of the Auckland War Memorial Museum

is carved the name Flers which is part of a ring of names around the

building's exterior.

These commemorate the battles of the Auckland Division. High Wood, Gravenstafel, Gallipoli, Le Quesnoy, Polygon Wood, Palestine and on the names roll. The building is a war memorial although the exigencies of marketing these days have seen those aspects down played which in turn raises all sorts of interesting questions about the exercise of public moneys.

It's better to leave these conundrums aside for the time being and walk into the museum. Climb the stairs past the cabinets of coins and the copies of Roman copies of Greek statues.

On the top floor are walls carved with the names of "... those from the Provincial District of Auckland who at the call of King and Country left all that was dear to them, endured hardness, faced danger and finally passed out of the sight of man..." as the inscription has it. J. Clark 25/738 (as opposed to J. Clark 11/1779) is on the wall to the right of the inscription on the third panel from the floor.

At the Museum you can consult the Roll of Honour in hard copy, that is a good old fashioned book, or on a database. The book is a sober and dignified tome published in 1922 and listing all the New Zealand dead of the Great War. It goes from Kenneth Abbot to Rudolph Zorn taking in 18,164 other names.

It contains an introduction which discusses the memorials and cemeteries overseas. It is hardly light reading. The pages with their listings of numbers, ranks, names, units and "Particulars of casualty" (Killed in action, Gallipoli, 25/4/15; Died of wounds, France, 5/10/18 &c) produce a kind of deadening at the sight of so much wastage. "Jesus, make it stop" you think as you leaf through it but of course it will never end.

The database has no such effect which speaks volumes about the ways we respond to media. What is it about a small screen that trivialises and numbs reaction? Instead of handling a kind of memorial you simply type in the name of the person you are searching for and it comes up on the screen. A virtual memorial.

The information is the same as in the book but without the serried ranks of names, row on row, the emotional effect is quite different but then this is a tool of research and not some kind of cultural artefact dedicated to "the memory of the fallen". For that we have to look further afield in "cyberspace".

There are many Internet sites concerned with the Great War. These are run by a range of individuals and organisations from lone hobbyists to government bodies.

Some of these are overtly memorial while others are more didactic. The urge to teach about these things is bound up with the urge to remember them and so the two overlap. This virtual network mirrors the actual string of cemeteries and memorials around the world. To turn one colourful phrase of cyber jargon, it augments the reality.

The features that web sites have such as interactivity, sound, graphics, video and hypertext are often aesthetically pleasing and help present such content as there may be. Ultimately though, the small screen version too soon induces the boredom of television.

The digital version of memory is overshadowed by the bulk of the stone memorials and the cemeteries' uniform headstones "2 ft. 6 in. high, 1 ft. 3 in. wide, and 3 in. thick ... so that general and private rest side by side ... equal in honour of their death ..." The sententious wit of cyberspace has it that on the Net no one knows you're a dog.

Film is a far more interesting medium than the underwhelming banalities of the small screen. The British were quick to realise its power to affect public opinion and the official cameramen Geoffrey Malins and J. B. McDowell were given more liberty than print journalists who most of the Army hated. The Generals regarded the press as tantamount to spies while the troops despised them for their jingoism.

The resulting film, Battle of the Somme, was shown throughout England in August and September of 1916 (The battle itself had a longer run from July to November). It was very successful wherever it was shown. There were twenty million attendances in its first six weeks. People were struck by its verisimilitude. They felt they were sharing in the experience that their loved ones were undergoing and so it was a propaganda triumph.

Its "shockingly" realistic scenes did stir a brisk correspondence in the Times about the morality of pandering to people's morbid interests. The Dean of Durham wrote "I beg leave respectfully to enter a protest against an entertainment which wounds the heart and violates the very sanctities of bereavement."

This has to be considered in the light of the social conditions of cinema going at the time. It was a diversion of the lower classes but this film attracted middle-class customers. A correspondent from Southport noted in the audience "several of the leading citizens in the district who are more usually to be found at a performance of legitimate drama of the 'intellectual' type". They even had to queue.

Audiences tended to supply their own soundtracks to the silent films of the day and watched them with some rowdiness and much vocal interjection. It was an early version of interactive media. The Somme film was watched in silence and almost with reverence although the marching scenes might draw the odd cheer.

Reactions to the film were complex and varied. One cinemagoer commented "Praise God, from whom all blessing flow, a few more Germans gone below". Frances Stevenson was the secretary and mistress of Prime Minister Lloyd George. Her brother had been killed. She wrote in her diary: "I have often tried to imagine what he went through, but now I know, and I shall never forget".

Now we can see it on video. On a small screen. The titles flicker as a piano soundtrack strikes up. Soldiers march and wave. Shells are stacked. Guns are fired. Shells burst over No Man's Land. More soldiers, they wave. Some smile and all are unselfconsciously curious about the camera.

The troops are in trenches on the morning of the 1st July, an hour or so before they go over. They are glassy eyed and the smiles are fixed. The Hawthorn mine is blown. Men climb from trenches. Soldiers run in the distance.

Shellfire. Wounded trickling back. A field station where a medical officer treats a man shot through both arms who puffs on a cigarette and stares at us. One title card reads "...in the background appear a battalion of Manchester Pioneers waiting to go down to the German trenches when captured". No one commented on the ambiguity at the time. The mail arrives. Dirty, ragged men smile. German corpses are piled in trenches. A burial party.

The realism of the battle scenes is lost to us now. We see one man fall as he climbs from a trench. He looks back at the camera and carefully folds his hands over his chest and crosses his legs. Most of this was filmed a few days before the attack at a training camp. The realism is in the eyes of the people who are about to go into battle or have just come out. The prisoners look especially pleased.

This is probably the first mass depiction of piles of corpses, a scene we at the tail end of this century are quite blasé about but which had a huge impact on those who saw the film in 1916. The entertainments of the modern cinema would certainly provoke the Dean of Durham.

This black and white silent film still affects by its relentlessness and silence. The intolerably nameless soldiers march and wave and smile at the camera. It is as mute and moving a testimony as the monuments with their rows of names.

From this film, it's a straight line of descent to the edit suites of CNN. Maybe in eighty years time the contrivances and deceptions of the modern version will be as obvious to people as the Battle of the Somme's effects.

In the meantime, the media colludes as ever in the interests of the military, government and business as the Gulf War Diversion illustrated. Isn't "Smart bombs" an oxymoron, albeit a very catchy one?

The Somme film seems more honest in some ways in that it shows some of the sights of warfare. CNN never showed us the huge carnage caused by "stupid" weapons during the Iraqi retreat let alone the pounding of their front lines before this.

Jocelyn Clark is not in the film. The New Zealand Division didn't go into the Somme until September. They attacked at 6.20 am on the 15th of that month. They were to advance 3,000 yards and capture the village of Flers which was by then a geographic expression.

Like all the villages in the area it was a smear of red brick dust on the churned up ground. This attack was the start of the third phase of the battle and Douglas Haig was using tanks for the first time in history. Clark's battalion was in the second wave.

Their exploits, if not their experiences, are contained in the dry volumes of the official histories. New Zealand's were written by a variety of authors and for the most part confine themselves to austere accounts of regimental history, Ormond Burton's books being a notable exception.

The language is clinical - trenches are "cleared", guns are "of the greatest assistance", objectives are "secured" "fine action" is performed by people as they bomb, bayonet and shoot each other or drag mangled friends back through stinking mud. Even Burton, who as a veteran has awareness of the suffering, uses this language.

There is a respectful tone about the follies and lunacies of the war which is a far cry from the often acerbic Australian history by C. W. Bean who takes care to criticise governments and generals when he sees fit, especially the English. Even the British histories are slightly less reverential.

These books are officially sanctioned memorials as much as the stone obelisks but their impact is diminished by the neutral tone and language. They preserve the outward events while ignoring the complexities of individual responses to utterly irrational and horrific experiences.

They are impersonal and lofty and stand like stone reliefs of battles, defeats and victories. These books differ from Assyrian friezes however in that they are not concerned with the "glory" of war or the exaltation of leaders, they are public acts of memory to the dead.

They capture several strands of the memory of the war. Burton hopes his history of the Auckland Brigade "may serve to quicken old memories and help many of you to live over again the great days when we marched and fought, bivouacked and billeted".

His comrades, "better ones a man could never have", were alive when he wrote the book and they often looked back on their war experience with nostalgia especially as the land they returned to rapidly became unfit for heroes, or anyone else, with depression and poverty all around.

This is one reaction which is often overlooked by the modern, populist view of the war and is lost to us directly now as the veterans are for the most part dead. The "disillusionment" war literature of the 1920s exemplified by Remarque's All quiet on the Western Front has become the dominant strain to some degree in the way we shape the war in our memory.

Personal accounts are one way of getting behind the austerities of the official histories and the clichés of the "Lions led by donkeys" version of the war as seen in Peter Weir's Gallipoli.

Many were published in the years after the war. There was a boom for collecting oral versions in the 70s and 80s which was prompted by the fact that many of those who could talk about such things would soon be silenced. This was another conscious act of memory in that these voices would all soon be lost but now they were recorded and transcribed.

The soldiers were ready to talk as well. It is an established part of the memory of the war that they weren't when they came back. That the experience was too remote from civilian life, the memories too painful, the horror unspeakable, the stories too shocking are all part of the explanation.

New Zealand's Great War literature reflects this. There were a few novels published with John A. Lee and Robyn Hyde being the foremost. As for poetry, there may have been many a mute, inglorious Colonial Owen or Sassoon but they left no trace. This laconic literary output is connected with the silence that was broken by a lot of men in their old age as they spoke. This is the famous New Zealand taciturnity at work.

Their accounts are interesting when put alongside the monumental official histories. The circumstances and motivations behind gathering them turn them into another kind of memorial but a much more personal one.

The Official History of the Rifle Brigade has a full account of the attack in which Clark died. "On the left, the 3rd Battalion found trouble at once. The wire in front of Flers Trench was practically intact, and, while held up by this obstacle, the leading companies suffered heavily at the hands of German machine-gunners and snipers." A Coy was in the lead under Captain Thomson. Perhaps this is when Clark was killed.

Lawrence Blyth was a private in the 4th Battalion of the Rifle Brigade. He was 92 when he recalled that day. "The barbed wire was never cut. Going over the top for the first time, no one knew what to expect. A soldier sees nothing."

The history goes on "Repeated efforts were made to break through the barrier ... but all attempts proved utterly unavailing. The men thereupon took cover in shell-holes and awaited the arrival of the tanks." They arrived at 10.30 am and crushed the wire while the people in Flers Trench were killed with grenades and bayonets. Clark might've still been alive and seen the new machines.

The shape of the tank is yet another image of this century. From the Spanish Civil War to the media sterilised Gulf War via Tiananmen Square, the image of tanks crashing through walls and crushing all before them is a universal symbol. Sassoon turned it on its makers in "Blighters" and also caught the split between the trenches and Blighty:

I'd like to see a Tank come down the stalls,

Lurching to rag-time tunes, or 'Home sweet Home',

And there'd be no more jokes in Music-halls

To mock the riddled corpses on Bapaume.

The tank became a new archetype like the one first instanced by zeppelins floating silvered in searchlights over London and dropping bombs.

The new technology was a mixed blessing according to Blyth. "We had four tanks allocated to the Division. I don't think the first one ever got past the starting line. One followed us up .. and stopped about a hundred yards behind our trench with the result that the Germans set to work to plaster it with artillery fire ... and we really got strafed." All the time British shells were falling short among the New Zealand troops.

The advance continued at 11.00. The remnants of the village were taken with an RFC pilot reporting cheering troops advancing down the main street behind a tank. These were from the Rifle Brigade but there was no main street left and no cheering is mentioned in the history.

"The effective strength had been sadly reduced by casualties throughout the long advance of two miles under fire and without a barrage ... the whole position, besides being under fire from both west and east, was enfiladed by machine guns ... At 3.20 pm the Brigade received orders from Division that the advance was to proceed no further ... "

This was New Zealand's "First day on the Somme" and has all the imagery we associate with the war such as artillery barrages, uncut wire, confusion and bungling, new technology and then squatting in holes under fire waiting for relief. The Division had 7,000 casualties in 23 days.

Gunner Hankins wrote about the Somme, "The ground there has been absolutely ploughed with shells and dead men (theirs and ours) are everywhere, pieces of men lay about the ground an arm here and leg and head there, it is a horrible sight. Some had even been blown up and pieces still remain in the trees."

The individual impact of such experiences is not part of the memorials officially sanctioned by the community which is where the missing are remembered. We have no records of what Clark saw or how he reacted. He is present in the literature as a name in Appendix II "The honoured dead" of the Rifle Brigade history. The list covers 31 pages.

There is one more stone memorial where his name is found. To find it you leave the Museum and drive through the suburbs of Auckland until you're deep in the farmland surrounding State Highway 2. On your left as you head south is the Red Fox Tavern. This is a squat complex of ugly buildings with a large car park.

Children cry and squabble

fitfully as their parents drink, talk and listen to a jukebox. On the

corner opposite it where Memorial Road joins the highway is the local war

memorial.

It is a stone obelisk surrounded by a low metal fence.

Beer bottles lie on the grass around it and its entrance faces away from the

pub and highway across the green land.

It is a stone obelisk surrounded by a low metal fence.

Beer bottles lie on the grass around it and its entrance faces away from the

pub and highway across the green land.

It has this inscription: "Erected by the residents of Maramarua and surrounding districts in memory of those men who fought and fell in the Great War 1914-1918".

Jocelyn Clark's name is on the side facing the highway. Below the names is inscribed "greater love hath no man". The obelisk is badly weathered. Clark's name is only just legible and some others are more or less effaced by time, the elements and neglect.

Monuments are a typical feature of the New Zealand landscape. Most were put up in the 1920s and often with much agonising and argument over siting, shape, function and lettering. They dot the country and are redolent of the imperial age and an ethos of patriotism and sacrifice which is decidedly unfashionable these days.

Erected by communities in recognition of something utterly unimaginable and alien, they stand amongst fast food outlets and parks where people play touch rugby for the honour of their workplace and mates. New Zealand's approach to sport always has had the tang of the militaristic about it and owes a lot to the experience of war.

The monuments are the focus of ANZAC Day ceremonies. This is one day which the country recognises as being special for a huge, tangled skein of reasons which involve awareness of nationhood and so a sense of separateness.

John Mulgan's "Man alone" is one version of a sense of separation and many of our films follow suit with their depictions of alienated and misunderstood outsiders lurking amongst the sunny pohutukawas and macrocarpa bushes.

These are the stock clichés of our post colonialist Zeitgeist and work as well as any other clichés although they seem a little tired in this age of cyber communication and cheap global travel. The godwits fly whenever they feel like it these days.

ANZAC Day has been a constant here since the first anniversary of the Gallipoli landings and has become over laden with meanings which are still being added. Some, along with some rituals, date back to the war years.

It was conceived generally and spontaneously as a day of remembrance for the dead. The marching of returned soldiers became a key part of it straight away. Local councils assumed various responsibilities in this commemoration which are often more honoured in the breach than the observance in this age of LATEs.

Pacifism, militarism, politics and religion are the currents that have swirled through these cultural channels at various times. In the late 1990s, crowds at dawn parades (instigated in 1939 after some returned soldiers saw it in Sydney in 1938) are increasing in size.

There is talk of using it as a de facto, all purpose New Zealand Day given that Waitangi Day has become a minefield. The one day on which we are all equal as are the remains of privates and generals beneath their standard issue headstones.

The way ANZAC Day admits fresh meanings and interpretations is what causes people to still mark and discuss it. It is a flexible and protean memorial. It is part of one landscape in the same way that the cenotaphs, arches and obelisks are part of another which now includes giant carrots and trout.

Of course Rifleman Clark never got to see all this let alone the things yet unseen in Johnsonville and Geraldine. I discovered his name and some things about his death. I found that his name was written in a lot of different ways which are examples of the ways we order our past experience - they make an academy and call it history - but all of this and its fascination spirals endlessly around a sensation of inarticulacy.

You stand at Caterpillar Valley, the Menin Gate or the Maramarua memorial and there is nothing to say in the knowledge of the experience such things mark.

Beside the private experience, the outward forms of the rituals, the debates and the monuments are the common signs of our continuous collective revision of the past. Our stories of the Great War and what followed from it are undergoing another transformation as they go from living memory to history.

This is neither good nor bad. Herodotus set the tone for history when he said "my business is to record what people say but I am by no means bound to believe it." The missing named on the memorials say as much as anyone.

Article contributed by Peter Hoar

The Parados was the side of a trench farthest from the enemy.

- Did you know?