Feature Articles - Vimy Ridge Today

Six years ago, both my

parents and I, planning a 'booze cruise' to France, decided instead to visit

the war grave of my great grandfather located in the tiny village of

Roclincourt, near Arras. After paying our respects we drove on to the

wonderfully preserved Vimy Ridge.

Six years ago, both my

parents and I, planning a 'booze cruise' to France, decided instead to visit

the war grave of my great grandfather located in the tiny village of

Roclincourt, near Arras. After paying our respects we drove on to the

wonderfully preserved Vimy Ridge.

The battle for Vimy Ridge from the 9-12 April 1917 was where Canada, as many commentators have argued, received its baptism of fire. It is not the job of this little account to detail these past glories, but only to give the reader an impression of the site on the day that we visited. And I make no apologies for any vagaries - it was six years ago and I was an uncouth teenager then!

Today, it is virtually impossible to believe that the scenes of death, despair, tragedy and glory were played out in and around Vimy. To be blunt, the area reminded me more of a park than the site of a bloody battlefield. Children raced into and out of the preserved trenches; people's dogs, let off their leads, yapped about; and couples walked hand in hand, pointing out various features to one another. Trees surrounded the site - their branches swaying lazily in the wind. Could a soldier of Vimy ever, even with the wildest of imaginations, believe that the hell in which he found himself would one day become such a place?

The

visitor centre is well worth investigating. Here they have a small,

but informative museum. The pictures displayed there highlight the

moonscape of shell holes that the area once was. Before the Canadian

offensive began, over 1,000,000 allied shells pulverised the ground.

And this saturation came on top of the incessant warfare that began in

October 1914 when the Germans first captured Vimy Ridge. The intensity

of the artillery is still evident today - grassy dips, ridges and bumps

ripple across the preserved part of the battlefield.

The

visitor centre is well worth investigating. Here they have a small,

but informative museum. The pictures displayed there highlight the

moonscape of shell holes that the area once was. Before the Canadian

offensive began, over 1,000,000 allied shells pulverised the ground.

And this saturation came on top of the incessant warfare that began in

October 1914 when the Germans first captured Vimy Ridge. The intensity

of the artillery is still evident today - grassy dips, ridges and bumps

ripple across the preserved part of the battlefield.

Now and then, a deep crater interrupts the geography. Physical reminders of the deadly cat and mouse game of saps and tunnels, the craters are still deep and precipitous despite the passing years. Many tunnels, both Allied and German, survive. This subterranean world can be visited on a guided tour. Unfortunately it was closed for routine inspection on the day we arrived.

Segments of trenches still survive. They are lined with cement filled sandbags, stone duckboards and are obviously well drained. Concrete trenches might offend some First World War aficionados, but the logistics of maintaining an accurate reconstruction would be impossible. They do, however, give the visitor an idea of the scale of building and the ingenuity that went into their construction. The small distance between some parts of the opposing lines was truly amazing. No wonder that many memoirs record overhearing the enemy's conversations and arguments. They were indeed the 'closest' of neighbours!

The

most distinctive feature on Vimy Ridge is Hill 145. Because of its height

and commanding line of sight, it was essential that the daunting position be

captured. The job fell to the 4th Canadian division. It was a tough nut to

crack. Following a tenacious and well-planned assault, however, Hill 145

fell into Allied hands with fewer casualties than would have been expected.

The

most distinctive feature on Vimy Ridge is Hill 145. Because of its height

and commanding line of sight, it was essential that the daunting position be

captured. The job fell to the 4th Canadian division. It was a tough nut to

crack. Following a tenacious and well-planned assault, however, Hill 145

fell into Allied hands with fewer casualties than would have been expected.

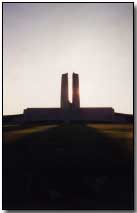

A towering memorial has been built on the hill's apex to celebrate, to remember and to mourn. Its two large white obelisks pierce the skyline. From a distance, there is something almost pharaonic and triumphant about them. The structure, bathed in bright light when I visited, looked spectacular. Glorious, but strangely desolate, I would say that this memorial is perhaps the greatest example of Great War remembrance architecture.

So the next time you plan a short trip or a booze cruise to France, why not head down to Arras instead? What better epitaph could there be to those who fell than Vimy Ridge? Under the gaze of its triumphant sentinel, the Canadian Memorial, we are all free to explore and come to terms with the meaning of World war One.

Text contributed by Simon Rees; present-day photographs copyright Octofish (reproduced with permission).

A 'Baby's Head' was a meat pudding which comprised part of the British Army field ration.

- Did you know?