Primary Documents - British Law Courts Review of the Sinking of the Lusitania, 7 May 1915

Reproduced below is the

text of the official British law courts review established in the aftermath

of the

sinking of the Lusitania on 7 May

1915 by

German U-boat U-20.

Although the review was primarily intended to determine the cause of the

disaster - this was clear enough - it also addressed (although briefly)

concerns that the ship was carrying munitions and that the life-boats were

leaky; in both cases the report's author, Lord Mersey, cleared the operating

company, Cunard, of any culpability. He also cleared the ship's crew

of any suggestion of incompetence.

Reproduced below is the

text of the official British law courts review established in the aftermath

of the

sinking of the Lusitania on 7 May

1915 by

German U-boat U-20.

Although the review was primarily intended to determine the cause of the

disaster - this was clear enough - it also addressed (although briefly)

concerns that the ship was carrying munitions and that the life-boats were

leaky; in both cases the report's author, Lord Mersey, cleared the operating

company, Cunard, of any culpability. He also cleared the ship's crew

of any suggestion of incompetence.

Click here to read the first of the U.S. government's official protests to the German government; click here to read Germany's response; click here to read the second U.S. note; click here to read the third.

The Sinking of the Lusitania - British Law Courts Report by Lord Mersey

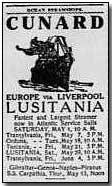

The Lusitania left New York at noon on the 1st of May, 1915. I am told that before she sailed notices were published in New York by the German authorities that the ship would be attacked by German submarines, and people were warned not to take passage in her.

In my view, so far from affording any excuse the threats serve only to aggravate the crime by making it plain that the intention to commit it was deliberately formed and the crime itself planned before the ship sailed.

Unfortunately the threats were not regarded as serious by the people intended to be affected by them. They apparently thought it impossible that such an atrocity as the destruction of their lives could be in the contemplation of the German Government. But they were mistaken: and the ship sailed.

The Ship's Speed

It appears that a question had arisen in the office of the Cunard Company shortly after the war broke out as to whether the transatlantic traffic would be sufficient to justify the Company in running their two big and expensive ships - the Lusitania and the Mauretania.

The conclusion arrived at was that one of the two (the Lusitania) could be run once a month if the boiler power were reduced by one-fourth. The saving in coal and labour resulting from this reduction would, it was thought, enable the Company to avoid loss though not to make a profit.

Accordingly six of the Lusitania's boilers were closed and the ship began to run in these conditions in November, 1914. She had made five round voyages in this way before the voyage in question in this inquiry. The effect of the closing of the six boilers was to reduce the attainable speed from 24 to 21 knots. But this reduction still left the Lusitania a considerably faster ship than any other steamer plying across the Atlantic.

In my opinion this reduction of the steamer's speed was of no significance and was proper in the circumstances.

The Torpedoing of the Ship

By May 7th the Lusitania had entered what is called the "Danger Zone," that is to say, she had reached the waters in which enemy submarines might be expected. The Captain had therefore taken precautions. He had ordered all the life-boats under davits to be swung out. He had ordered all bulkhead doors to be closed except such as were required to be kept open in order to work the ship.

These orders had been carried out. The portholes were also closed. The lookout on the ship was doubled - two men being sent to the crow's nest and two men to the eyes of the ship. Two officers were on the bridge and a quartermaster was on either side with instructions to look out for submarines. Orders were also sent to the engine-room between noon and 2 p.m. of the 7th to keep the steam pressure very high in case of emergency and to give the vessel all possible speed if the telephone from the bridge should ring.

Up to 8 a.m. on the morning of the 7th the speed on the voyage had been maintained at 21 knots. At 8 a.m. the speed was reduced to 18 knots. The object of this reduction was to secure the ship's arrival outside the bar at Liverpool at about 4 o'clock on the morning of the 8th, when the tide would serve to enable her to cross the bar into the Mersey at early dawn.

Shortly after this alteration of the speed a fog came on and the speed was further reduced for a time to 15 knots. A little before noon the fog lifted and the speed was restored to 18 knots, from which it was never subsequently changed. At this time land was sighted about two points abaft the beam, which the Captain took to be Brow Head; he could not, however, identify it with sufficient certainty to enable him to fix the position of his ship upon the chart.

He therefore kept his ship on her course, which was S. 87 E. and about parallel with the land until 12.40, when, in order to make a better landfall he altered his course to N. 67 E. This brought him closer to the land, and he sighted the Old Head of Kinsale.

He then (at 1.40 p.m.) altered his course back to S. 87 E., and having steadied his ship on that course, began (at 1.50) to take a four-point bearing. This operation, which I am advised would occupy 30 or 40 minutes, was in process at the time when the ship was torpedoed, as hereafter described.

At 2 p.m. the passengers were finishing their midday meal. At 2.15 p.m., when ten to fifteen miles off the Old Head of Kinsale, the weather being then clear and the sea smooth, the Captain, who was on the port side of the lower bridge, heard the call, "There is a torpedo coming, sir," given by the second officer.

He looked to starboard and then saw a streak of foam in the wake of a torpedo travelling towards his ship. Immediately afterwards the Lusitania was struck on the starboard side somewhere between the third and fourth funnels. The blow broke number 5 life-boat to splinters. A second torpedo was fired immediately afterwards, which also struck the ship on the starboard side. The two torpedoes struck the ship almost simultaneously.

Both these torpedoes were discharged by a German submarine from a distance variously estimated at from two to five hundred yards. No warning of any kind was given. It is also in evidence that shortly afterwards a torpedo from another submarine was fired on the port side of the Lusitania. This torpedo did not strike the ship: and the circumstance is only mentioned for the purpose of showing that perhaps more than one submarine was taking part in the attack.

The Lusitania on being struck took a heavy list to starboard and in less than twenty minutes she sank in deep water. Eleven hundred and ninety-eight men, women, and children were drowned.

Sir Edward Carson, when opening the case, described the course adopted by the German Government in directing this attack as "contrary to International Law and the usages of war," and as constituting, according to the law of all civilized countries, "a deliberate attempt to murder the passengers on board the ship."

This statement is, in my opinion, true, and it is made in language not a whit too strong for the occasion. The defenceless creatures on board, made up of harmless men and women, and of helpless children, were done to death by the crew of the German submarine acting under the directions of the officials of the German Government.

In the questions submitted to me by the Board of Trade I am asked, "What was the cause of the loss of life?" The answer is plain. The effective cause of the loss of life was the attack made against the ship by those on board the submarine. It was a murderous attack because made with a deliberate and wholly unjustifiable intention of killing the people on board.

German authorities on the laws of war at sea themselves establish beyond all doubt that though in some cases the destruction of an enemy trader may be permissible, there is always an obligation first to secure the safety of the lives of those on board. The guilt of the persons concerned in the present case is confirmed by the vain excuses which have been put forward on their behalf by the German Government as before mentioned.

One witness, who described himself as a French subject from the vicinity of Switzerland, and who was in the second-class dining-room in the after part of the ship at the time of the explosion, stated that the nature of the explosion was "similar to the rattling of a maxim gun for a short period," and suggested that this noise disclosed the "secret" existence of some ammunition. The sound, he said, came from underneath the whole floor.

I did not believe this gentleman. His demeanour was very unsatisfactory. There was no confirmation of his story, and it appeared that he had threatened the Cunard Company that if they did not make him some immediate allowance on account of a claim which he was putting forward for compensation, he would have the unpleasant duty of making his claim in public, and, in so doing, of producing "evidence which will not be to the credit either of your Company or of the Admiralty." The Company had not complied with his request.

It may be worth while noting that Leith, the Marconi operator, was also in the second-class dining-saloon at the time of the explosion. He speaks of but one explosion. In my opinion there was no explosion of any part of the cargo.

Orders Given and Work Done After the Torpedoing

The Captain was on the bridge at the time his ship was struck, and he remained there giving orders until the ship foundered. His first order was to lower all boats to the rail. This order was obeyed as far as it possibly could be. He then called out, "Women and children first."

The order was then given to hard-a-starboard the helm with a view to heading towards the land, and orders were telegraphed to the engine-room. The orders given to the engine-room are difficult to follow and there is obvious confusion about them. It is not, however, important to consider them, for the engines were put out of commission almost at once by the inrush of water and ceased working, and the lights in the engine room were blown out.

Leith, the Marconi operator, immediately sent out an S.O.S, signal, and, later on, another message, "Come at once, big list, 10 miles south Head Old Kinsale." These messages were repeated continuously and were acknowledged. At first, the messages were sent out by the power supplied from the ship's dynamo; but in three or four minutes this power gave out and the messages were sent out by means of the emergency apparatus in the wireless cabin.

All the collapsible boats were loosened from their lashings and freed so that they could float when the ship sank.

The Launching of the Life-boats

Complaints were made by some of the witnesses about the manner in which the boats were launched and about their leaky condition when in the water. I do not question the good faith of these witnesses, but I think their complaints were ill-founded.

Three difficulties presented themselves in connection with the launching of the boats.

First, the time was very short: only twenty minutes elapsed between the first alarm and the sinking of the ship.

Secondly, the ship was under way the whole time: the engines were put out of commission almost at once, so that the way could not be taken off.

Thirdly, the ship instantly took a great list to starboard, which made it impossible to launch the port side boats properly and rendered it very difficult for the passengers to get into the starboard boats. The port side boats were thrown inboard and the starboard boats inconveniently far outboard.

In addition to these difficulties there were the well-meant but probably disastrous attempts of the frightened passengers to assist in the launching operations. Attempts were made by the passengers to push some of the boats on the port side off the ship and to get them to the water. Some of these boats caught on the rail and capsized. One or two did, however, reach the water, but I am satisfied that they were seriously damaged in the operation.

They were lowered a distance of 60 feet or more with people in them, and must have been fouling the side of the ship the whole time. In one case the stern post was wrenched away. The result was that these boats leaked when they reached the water.

Captain Anderson [Note: the second in command, under the chief commander, Captain Turner] was superintending the launching operations, and, in my opinion, did the best that could be done in the circumstances. Many boats were lowered on the starboard side, and there is no satisfactory evidence that any of them leaked.

There were doubtless some accidents in the handling of the ropes, but it is impossible to impute negligence or incompetence in connection with then.

The conclusion at which I arrive is that the boats were in good order at the moment of the explosion and that the launching was carried out as well as the short time, the moving ship and the serious list would allow.

Both the Captain and Mr. Jones, the First Officer, in their evidence state that everything was done that was possible to get the boats out and save lives, and this I believe to be true.

Captain Turner exercised his judgment for the best. It was the judgment of a skilled and experienced man, and although others might have acted differently and perhaps more successfully, he ought not, in my opinion, to be blamed.

The whole blame for the cruel destruction of life in this catastrophe must rest solely with those who plotted and with those who committed the crime.

Source: Source Records of the Great War, Vol. III, ed. Charles F. Horne, National Alumni 1923

At the Battle of Sarikamish the Turks suffered a disastrously high 81% casualty rate.

- Did you know?