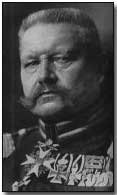

Primary Documents - Paul von Hindenburg on the Opening of the Lys Offensive, 9 April 1918

Reproduced below is German

Chief of Staff

Paul von Hindenburg's account

of the opening of the second German Spring Offensive of 1918, at the Lys

valley on 9 April 1918.

Reproduced below is German

Chief of Staff

Paul von Hindenburg's account

of the opening of the second German Spring Offensive of 1918, at the Lys

valley on 9 April 1918.

Intended by Erich Ludendorff as a means of weakening and confusing the Allies the attack along the Lys valley attained such startlingly effective initial results that Ludendorff took the decision to convert the effort into a full-scale offensive against British forces stationed there.

As Hindenburg noted in his account the German offensive very nearly succeeded in breaking through the British lines, opening an artillery path to the Channel Ports; however French reinforcements prevented a German breakthrough, prompting a German return to a defensive posture.

Click here to read British Commander-in-Chief Sir Douglas Haig's Special Order of the Day, dated 11 April 1918, in which he appealed to the British Army "to fight it out" to the end. Click here to read Currie's appeal to the Canadian Corps for courage shortly before they entered fighting during the Lys offensive.

Paul von Hindenburg on the Opening of the Lys Offensive, 9 April 1918

In winter the low-lying area of the Lys river-valley was to a large extent flooded, and in spring it was often nothing but a marsh for weeks on end - a real horror for the troops holding the trenches at this point.

North of the Lys the ground gradually rose, and then mounted sharply to the great group of hills which had its mighty pillars at Kemmel and Cassel.

It was perfectly hopeless to think of carrying out such an attack before the valley of the Lys was to some extent passable. In normal circumstances of weather, we could only expect the ground to become dry enough by the middle of April.

But we thought we could not wait until then to begin the decisive conflict in the West. We had to keep the prospects of American intervention steadily before our eves.

Notwithstanding these objections to the attack, we had the scheme worked out, at any rate in theory. In this working out we provided for the eventuality that our operation at St. Quentin would compel the enemy's leaders to withdraw large reserves from the group in Flanders to meet our breakthrough there.

This eventuality had materialized by the end of March. As soon as we saw that our attack to the west must come to a standstill, we decided to begin our operations on the Lys front.

An inquiry addressed to the Army Group of the Crown Prince Rupprecht elicited the reply that, thanks to the dry spring weather, the attack across the valley of the Lys was already feasible.

The enterprise was now taken in hand by the Army Headquarters Staff and the troops with amazing energy.

On April 9, the anniversary of the great crisis at Arras, our storm troops rose from their muddy trenches on the Lys front from Armentieres to La Bassee.

Of course they were not disposed in great waves, but mostly in small detachments and diminutive columns which waded through the morass which had been upheaved by shells and mines, and either picked their way towards the enemy lines between deep shell-holes filled with water or took the few firm causeways.

Under the protection of our artillery and trench-mortar fire, they succeeded in getting forward quickly in spite of all the natural and artificial obstacles, although apparently neither the English nor the Portuguese, who had been sandwiched in among them, believed it possible.

Most of the Portuguese troops left the battlefield in wild flight, and once and for all retired from the fighting.

It must be admitted that our exploitation of the surprise and of the Portuguese failure met with the most serious obstacles in the nature of the ground. It was only with the greatest difficulty that a few ammunition wagons were brought forward behind the infantry.

Yet the Lys was reached by the evening and even crossed at one point. Here again the decision was to be expected only in the course of the next few days. Our prospects seemed favourable.

On April 10th Estaires fell into our hands and we gained more ground north-west of Armentieres. On the same day our front of attack was extended to the region of Wytschaete. We again stormed the battered ruins of the much-fought-for Messines.

The next day brought us more successes and fresh hopes. Armentieres was evacuated by the enemy and we captured Merville. From the south we approached the first terrace of the great group of hills from which our opponent could see our whole attack and command it with his artillery.

From now on progress became slower. It soon came to a stop on our left wing, while our attack in the direction of Hazebrouck was slowly becoming paralysed. In our centre we captured Bailleul and set foot on the hills from the south. Wytschaete fell into our hands, but then this first blow was exhausted.

The difficulties of communication across the Lys valley which had to be overcome by our troops attacking from the south had been like a chain round our necks. Ammunition could only be brought up in quite inadequate quantities, and it was only thanks to the booty the enemy had left behind on the battlefield that we were able to keep our troops properly fed.

Our infantry had suffered extremely heavily in their fight with the enemy machine-gun nests, and their complete exhaustion threatened unless we paused in our attack for a time.

On the other hand, the situation urgently exacted an early decision. We had arrived at one of those crises in which the continuation of the attack is extremely difficult, but when the defence seems to he wavering. The release from such a situation can only come from a further attack and not by merely holding on.

We had to capture Mount Kemmel. It had lain like a great hump before our eyes for years. It was only to be expected that the enemy had made it the key to his positions in Flanders.

The photographs of our airmen revealed but a portion of the complicated enemy defence system at this point. We might hope, however, that the external appearance of the hill was more impressive than its real tactical value.

We had had experiences of this kind before with other tactical objectives. Picked troops which had displayed their resolution and revealed their powers at the Roten-Tunn Pass, and in the fighting in the mountains of Transylvania, Serbian Albania and the Alps of Upper Italy, might once more make possible the seemingly impossible.

A condition precedent to the success of our further attacks in Flanders was that the French High Command should be compelled to leave the burden of the defence in that region to their English Allies.

We therefore first renewed our attacks at Villers-Bretonneux on April 24th, hoping that the French commander's anxiety about Amiens would take precedence of the necessity to help the hard-pressed English friends in Flanders.

Unfortunately this new attack failed. On the other hand, on April 25th the English defence on Mount Kemmel collapsed at the first blow. The loss of this pillar of the defence shook the whole enemy front in Flanders.

Our adversary began to withdraw from the Ypres salient which he had pushed out in months of fighting in 1917. Yet to the last Flemish city he clung as if to a jewel which he was unwilling to lose for political reasons.

But the decision in Flanders was not to be sought at Ypres, but by attacking in the direction of Cassel. If we managed to make progress in that quarter, the whole Anglo-Belgian front in Flanders would have to be withdrawn to the west.

Just as our thoughts had soared beyond Amiens in the previous month, our hopes now soared to the Channel Coast. I seemed to feel how all England followed the course of the battle in Flanders with bated breath.

After that giant bastion, Mount Kemmel, had fallen, we had no reason to flinch from the difficulties of further attacks. We must have Cassel at least! From that vantage point the long-range fire of our heaviest guns could reach Boulogne and Calais.

Both towns were crammed full with English supplies, and were also the principal points of debarkation of the English armies. The English army had failed in the most surprising fashion in the fight for Ketnmel. If we succeeded in getting it to ourselves at this point, we should have a certain prospect of a great victory.

If no French help arrived, England would probably be lost in Flanders. Yet in England's dire need this help was once more at hand. French troops came up with bitter anger against the friend who had surrendered Kemmel, and attempted to recover this key position from us. It was in vain.

But our own last great onslaught on the new Anglo-French line at the end of April made no headway.

On May 1st we adopted the defensive in Flanders, or rather, as we then hoped, passed to the defensive for the time being.

Twice had England been saved by France at a moment of extreme crisis. Perhaps the third time we should succeed. If we reached the Channel Coast we should lay hands directly on England's vital arteries.

In so doing we should not only be in the most favourable position conceivable for interrupting her maritime communications, but our heaviest artillery would be able to get a portion of the South Coast of Britain under fire.

The mysterious marvel of technical science, which was even now sending its shells into the French capital from the region of Laon, could be employed against England also.

Source: Source Records of the Great War, Vol. VI, ed. Charles F. Horne, National Alumni 1923

A cartwheel was a particular type of aerial manoeuvre.

- Did you know?