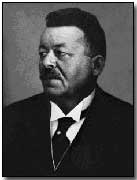

Who's Who - Friedrich Ebert

Friedrich Ebert (1871-1925)

served briefly as German Chancellor shortly before Germany's defeat in the

First World War and as the country's first post-war President until his

death in 1925.

Friedrich Ebert (1871-1925)

served briefly as German Chancellor shortly before Germany's defeat in the

First World War and as the country's first post-war President until his

death in 1925.

Born on 4 February 1871 in Heidelberg the son of a master tailor, Ebert learned his father's trade while young and initially travelled throughout Germany as a journeyman saddler.

With an early interest in current affairs Ebert developed Social Democratic Party (SPD) leanings, and fostered a sympathy for trade union causes (at that time much reviled by the ruling elite). He subscribed to the revisionist school of gradual constitutional reform. More pragmatically he quickly developed a concern for the improvement of the conditions of the common working man.

1905 saw Ebert's appointment as Secretary General of his party, which was at that point in the ascendancy with a growth both in popular support and party membership. He worked to improve party administration and introduced such basic necessities as typewriters.

In 1913 Ebert succeeded August Bebel as SPD leader, a year after he was elected to the Reichstag to represent his party. He was to oversee his party's crucial role in a most critical and tumultuous period in Germany's history.

It was Ebert who - following an extended holiday during the July Crisis of 1914 - prevailed upon his party to support the government's bid for war appropriations. Although socialist by nature the SPD's support of the government was very much in line with their counterparts throughout Europe.

Despite Ebert's unconditional support for the government's conduct of the war his party was nevertheless viewed as dangerous revolutionaries by many in the military high command as well as by members of the government.

By 1917 the national political consensus had effectively dissolved and Ebert's party was as greatly affected as others. In March that year a left-wing faction split and established the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD), simultaneously declaring total opposition to the government's conduct of the war.

Yet another group split from the SPD and formed the markedly more left-wing Communist Party of Germany (KPD). Their aim was nothing less than social revolution. This went far beyond the scope of remedy sought by Ebert who remained in favour of a parliamentary democracy. In this the SPD were supported in the so-called 'Black-Red-Gold' coalition by the Catholic Centre Party.

With military defeat imminent Ebert supported the creation of a coalition government in October 1918 with Prince Max von Baden at its head. Desperate to avoid revolution Ebert argued for extensive constitutional reform to forestall the growing influence of the extreme left-wing and widespread public discontent.

In the event Ebert lost his race to establish a constitutional monarchy. On 9 November his close colleague Philipp Scheidemann announced from the Reichstag balcony the creation of a German republic without consulting either Ebert or Max von Baden.

The same day Max von Baden announced his own retirement and while accepting Scheidemann's proclamation as a fait accompli handed over power to Ebert (thereby earning him the undying enmity of the country's right-wing throughout the 1920s).

The following day, 10 November 1918, Ebert attempted to establish a wholly socialist government, having accepted the impossibility of now establishing a regency for the deposed Wilhelm II. Ebert termed his administration the Council of People's Representatives, deriving his support from the Workers and Soldiers Council, a Berlin-based organisation. (Click here to read two of Ebert's public statements on the new government.)

Keen to ensure the supremacy of a freely elected parliament at the earliest opportunity, Ebert desired a liberal rather than socialist complexion to the coalition government.

The consequent elections of January 1919 gave the Black-Red-Gold coalition a notable majority in the Reichstag and Philipp Scheidemann became the republic's first Chancellor. A new constitution, the Weimar Constitution, was also unveiled (named after the town in which it was drawn up). Ebert himself was elected the nation's first President. (Click here to read Ebert's opening address as President to the new German assembly on 7 February 1919; click here to read the text of a follow-up speech four days later.)

Determined to reorganise the structure of the Reich and establish a unitary state Ebert was nevertheless frustrated by resistance shown by the old German states, a campaign for reform largely overshadowed by bloody civil uprisings.

The inaugural years of the first Weimar government were taken up in suppressing left-wing uprisings staged by both socialist and communist elements. In order to maintain order Ebert was required to rely upon the support of the Freikorps, largely comprised of former army officers who chose more to wage a war of hate against the left rather than out of any respect for the new republic.

The elections of 6 June 1920 resulted in the coalition government losing its parliamentary majority, chiefly as a consequence of the widely reviled Treaty of Versailles, for which Ebert and his coalition partners received much of the blame.

Remaining as President Ebert supported the passive resistance of the coal workers of the Ruhr in January 1923 when France occupied the region following Germany's default on coal deliveries as specified in the Versailles treaty. In the midst of the crisis Ebert appointed the rightist Gustav Stresemann to bring the situation under control, sparking a government walkout by his own party.

The same year, 1923, Ebert acted to quash Hitler's attempted beer-hall putsch. The price of continuing military support was high: a promise from Ebert not to reform the officer corps, thus guaranteeing the ongoing involvement of the military in German government.

Ebert died on 28 February 1925 in Berlin at the age of 54, his death hastened by the decision of a court which labelled him guilty of high treason for his support of munitions strikers during World War One.

He died widely criticised by all sides: by the left for betraying the revolution and by the right for being a leading figure responsible for stabbing the army in the back towards the close of war - and, of course, as the man who signed the hated Treaty of Versailles.

He was succeeded as President by the former leader of the wartime Third Supreme Command, Paul von Hindenburg.

By 1918 the percentage of women to men working in Britain had risen to 37% from 24% at the start of the war.

- Did you know?