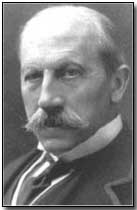

Who's Who - Alfred Milner

Lord Alfred Milner

(1854-1925), having already enjoyed a successful career as a colonial

administrator, was brought into

David Lloyd George's War Cabinet as Minister of War in the final seven

months of the war.

Lord Alfred Milner

(1854-1925), having already enjoyed a successful career as a colonial

administrator, was brought into

David Lloyd George's War Cabinet as Minister of War in the final seven

months of the war.

A leading imperialist, Milner was born on 23 March 1854 in Hesse-Darmstadt in Germany of British and German ancestry. A notable student at Oxford he was elected a fellow of New College in 1872. He briefly turned to practicing law in 1881 but soon chose instead a career in journalism, writing for the Pall Mall Gazette.

In spite of his pronounced imperialistic views Milner stood as a Liberal candidate for Parliament in 1885 - unsuccessfully - before taking up a position as private secretary to the then-Chancellor, George Goschen.

His fame and career was however carved in colonial appointments abroad, first in Egypt from 1889-92, from which he emerged to write England and Egypt. After five years as chairman of the Inland Revenue (during the course of which he was knighted, in 1895) he was appointed High Commissioner in south Africa and Governor of the Cape Colony in 1897.

As High Commissioner Milner played a prominent role in bringing about war between Britain and the Boers, taking a high hand in dealings with the Orange Free State and the Transvaal.

Refusing to compromise on demands permitting British residents in the Transvaal full citizenship rights after five years' residence (among other issues), Milner's intransigence eventually led to a declaration of war from the two Boer republics on 11 October 1899 who viewed Milner's - and Britain's - interests with deep suspicion.

British success followed by annexation of both former Boer republics in 1901 brought Milner a new post as Britain's administrator for the Orange Free State and the Transvaal, although he continued in his role as High Commissioner, negotiating the Peace of Vereeniging with Lord Kitchener of 31 May 1902. Ultimate success in South Africa brought Milner rewards: he was made a baron in 1901 and a viscount in 1902.

Tasked with the post-war settlement and regeneration of South Africa, Milner brought with him to South Africa his celebrated 'kindergarten', a group of ambitious young administrators whose careers throve both in South Africa and in later life (and included the young author John Buchan). When brought into Lloyd George's War Cabinet during World War One Milner brought back a number of these administrators to serve among his staff.

Milner's approach to the administration of the new South Africa continued to be divisive however. His insistence that education be conducted solely in English served to antagonise the Boers; even less successful (where it caused outrage at home) was his plan to draft in Chinese labour to work the South African goldmines, owing to a lack of necessary British labour.

Milner further suggested that the Transvaal be permitted only a representative government rather than granted self-rule; a recommendation that was rejected by Prime Minister Herbert Asquith.

Returning to England in 1905 he announced his intention to retire from public life, although he continued to air his decidedly right-wing views in the House of Lords, where he was an active member. In 1913 he published The Nation and the Empire.

Co-opted from private business interests into the government in 1914 to organise coal and food production, Lloyd George's appointment as Prime Minister in December 1916 led to Milner's elevation to the War Cabinet.

On 19 April 1918 he was appointed Minister of War, replacing Lord Derby. Milner - unlike Derby but in line with Lloyd George - was an enthusiastic advocate of the creation of an inter-allied wartime command, led by Ferdinand Foch.

Wary of the growing Bolshevik threat Milner came out in favour of an early peace settlement - and thereafter intervention with anti-Bolshevik forces in Russia.

With the end of the First World War Milner was appointed Colonial Secretary and attended the Paris Peace Conference. Milner's subsequent recommendation that Egypt be granted a form of independence was rejected by the Cabinet, leading to Milner's resignation in 1921.

1923 saw Milner publish Questions of the Hour. He died on 13 May 1925 in Kent aged 71.

Observation balloons were referred to as 'sausages'.

- Did you know?