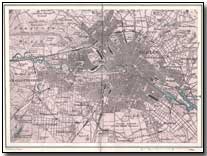

Feature Articles - The Bloodhounds of Berlin

It was a chilly January night in Berlin and a

group of soldiers and officers were milling around the back entrance to the Eden

Hotel when the first prisoner,

Karl Liebknecht, was led out.

It was a chilly January night in Berlin and a

group of soldiers and officers were milling around the back entrance to the Eden

Hotel when the first prisoner,

Karl Liebknecht, was led out.

He was a small moustached man, in his 40s with receding hair that was black, curly and matted with blood. One of the soldiers, Otto Runge, lunged forward swinging his rifle as a club. The butt crashed across the prisoner's head sending him sprawling.

Semi-conscious he was dragged into a car, which then sped off towards Tiergarten Park. Once there, the vehicle came to a halt and the battered man was ordered out. Staggering forward he was oblivious to the pistols raised behind his back. The assassination was over in a matter of seconds.

Twenty minutes after the first prisoner's departure, a second 'criminal', Rosa Luxemburg, stumbled out of the hotel. This diminutive woman was also in her 40s. Again Runge rushed forward using his weapon as a club. This time the victim collapsed – either dead or dying. She was thrown into the back of another waiting car, which drove around 100 yards when a pistol shot was heard from within its interior...

The New Republic

In September 1918 Germany's Supreme Command realised that their country was on

it last legs and

decided to sue for peace and, in order to gain more favourable

terms, set up a constitutional monarchy.

In September 1918 Germany's Supreme Command realised that their country was on

it last legs and

decided to sue for peace and, in order to gain more favourable

terms, set up a constitutional monarchy.

General Ludendorff was replaced by General Wilhelm Groener and Prince Max von Baden became Imperial Chancellor. But while the Supreme Command worried itself over the armistice terms, the German people seethed with indignation – millions had been sent to the grave for nothing. The hostility was further heightened by stringent rationing that was now leading to starvation.

With the war lost, the socialists in German society saw a chance to manoeuvre into power. The SPD (the majority socialists), were the largest party with the greatest support in Germany – their socialism was calm and methodical.

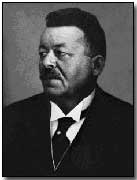

They were fronted by Fredrich Ebert, a podgy man with a gruff expression. He was an excellent organiser and was capable of taking decisive actions. Gustav Noske was to become his right-hand man. Tall and thickly built, Noske was a good speaker, with the ability of getting his enemies to bend to his will through words alone. But Noske was also ruthless enough to use violence to obtain his goals.

As the days wore on, the situation in Berlin and the country worsened. In early

November, the sailors of the High Seas fleet at Kiel

had revolted, although they

were calmed by the brilliant realpolitik of Noske who had been especially sent

to tame the mutiny.

As the days wore on, the situation in Berlin and the country worsened. In early

November, the sailors of the High Seas fleet at Kiel

had revolted, although they

were calmed by the brilliant realpolitik of Noske who had been especially sent

to tame the mutiny.

Many of the sailors, however, upped sticks and headed either to other major ports or to the capital. Of the latter, a large group numbering around 3,000 took over the Imperial Palace – the Schloss – and the imposing Imperial stables – the Marstall. They named themselves the People's Naval Division. Other destabilising elements were in Berlin and other cities: army deserters roamed the streets alongside communists, anarchists and criminal gangs.

Despite the growing chaos, the SPD had initially attempted to work with Prince Max von Baden's government. Unfortunately, Max von Baden's attempts to secure the Kaiser's abdication were painstakingly slow and when he did finally receive confirmation that the Emperor was stepping down, it was too late.

Massed protests and strikes against the government and the monarchy were sweeping the nation, particularly in Berlin. The SPD, now fearful of losing popular support, withdrew from von Baden's government, leaving him no choice but to hand over power and the Chancellorship to them on 9 November.

That evening, one of Ebert's

colleagues,

Philip Scheidemann, announced

the foundation of the German Republic

to protesters gathered below a set of French windows at the Reichstag.

That evening, one of Ebert's

colleagues,

Philip Scheidemann, announced

the foundation of the German Republic

to protesters gathered below a set of French windows at the Reichstag.

Ebert was livid – how could he be an Imperial Chancellor of a Republic? Fortunately, constitutional complexities were far from the minds of most Germans. The new Chancellor's main tasks were to secure the armistice, maintain power and then to gain a democratic mandate through elections. He faced many enemies and, ironically, the greatest threat was not from the right, but from the left.

Danger From The Left

The Independent Socialists, the USPD, had spilt from the SPD when the former refused to continue supporting total war. The right of their party, however, still felt able to work with Ebert. On the other hand, the far left of the USPD opposed the SPD's stance and wanted to sweep away the old order entirely.

In Berlin the USPD had taken over the city police when Emil Eichhorn, an extreme leftist of the party, had walked to the police headquarters on the Alexanderplatz, shoved his way through a large demonstration, entered the building and then brazenly announced: "I am the new police president."

With a crowd baying for their blood, the policemen were keen to get out the building alive and the new 'police president' offered them a chance to leave unharmed. Eichhorn was duly appointed.

The Spartacists were further to the left of the USPD; their core support was

small and based in the working class slums. Their unusual name was an invention

of their leader, the fiery Karl Liebknecht.

The Spartacists were further to the left of the USPD; their core support was

small and based in the working class slums. Their unusual name was an invention

of their leader, the fiery Karl Liebknecht.

During the war he had issued flyers deriding the Kaiser, but to avoid arrest he signed them 'Spartacus'. Liebknecht was a brilliant orator, but he was also impulsive and disorganised.

Supporting him was Rosa Luxemburg, a polish born Jew who was also a good speaker, as well as an excellent theologian. She frowned upon Liebknecht's calls for direct action as too pre-emptive and dangerous, especially when their militant supporters, the Spartacists, were still disorganised.

Winter Temperature Rising

With the armistice signed, Germany prepared to welcome home the millions of men that had served in the Imperial Armies. But in Berlin, as in most parts of the country, many had already walked away from the army to return home. Others went over to the far left. Some stayed in their barracks, half heartily carrying on with their duties.

Even then, a right-wing putsch was attempted by using the units still available in and around Berlin. The aim of the putsch was to rid the government of Independents and was probably organised in connivance with the SPD.

Several hundred troops surrounded the Chancellery, while others had rounded

up prominent USPD men.

Several hundred troops surrounded the Chancellery, while others had rounded

up prominent USPD men.

They proclaimed Ebert 'President', although the Chancellor displayed a distinct lack of enthusiasm and refused to support them outright.

Having failed to secure Ebert's support, the revolutionaries hastily retreated. However, on central Chauseestrasse tragedy struck. An army machine gun opened fire on a Spartacist demonstration, killing 16 and injuring 12.

The Spartacists claimed Ebert had organised the putsch and then, having seen the lack of troops, backed off disclaiming all knowledge of events – that the investigation into the massacre was suspiciously halted points towards SPD foul-play somewhere along the line.

Ebert now waited for nine first-rate Imperial Army divisions to return to Berlin. With them on side he could begin to decisively manoeuvre against his enemies and keep the peace. The divisions arrived in the capital on 11 December. But again, most of the soldiers simply walked away, with only a fraction of those available returning to their barracks and reporting for duty.

The Battle Begins

The People's Naval Division, having seen how quickly these army units dissolved,

began to flex its muscles – they began to demand money and supplies.

The People's Naval Division, having seen how quickly these army units dissolved,

began to flex its muscles – they began to demand money and supplies.

Exasperated by the threats, the Chancellor decided to starve the sailors out by withholding their pay – starting with their Christmas 'bonus' of 80,000 marks, a sizable sum at that time.

They would only receive their money once they had evacuated the Schloss, handed its keys to Otto Wels (military governor of Berlin) and made arrangements to leave the Marstall. After this, Ebert hoped they could be pressured into disbanding for good.

Wishing to maintain their life of comparative luxury, the sailors decided to try and negotiate with the USPD, their natural allies. On 23 December, a delegation arrived at the Chancellery with the palace keys wanting to talk with USPD representatives.

Each Independent suggested they visit another member of the party higher up the 'food chain'. Eventually, the sailors were told to find Ebert. They were forced to wait, however, because the Chancellor was out to lunch at that time.

Meanwhile, other sailors had arrived at Wels' office demanding their pay. Wels made some phone calls but could receive no precise information as to the whereabouts of the keys. He put the phone down and effectively told the sailors that there was 'nothing doing'. Enraged, they tore up Wels' office, beat its occupant for good measure, and then took him and two of his subordinates hostage.

The men would be released once the sailors received the 80,000 marks. To speed the government's decision, a large contingent left the Marstall, marched to the Chancellery and refused to let anyone either enter or leave the building.

Ebert rushed to the scene and told the angry sailors to remain calm, declaring that his government would be willing to negotiate. He then went to his office and contacted Supreme Command via his secret telephone. The army told Ebert that their soldiers would march into the centre of Berlin and 'set you free'.

First Blood

As the People's Naval Division sailors straggled back to the Schloss and

Marstall to celebrate what they believed to be a government capitulation, around

800 men of the Imperial Horse Guards were heading towards Berlin.

As the People's Naval Division sailors straggled back to the Schloss and

Marstall to celebrate what they believed to be a government capitulation, around

800 men of the Imperial Horse Guards were heading towards Berlin.

When the sailors heard that soldiers were approaching, they demanded that the army retire – otherwise they would stand and fight. Ebert began to worry; he did not want street fighting to erupt in the centre of Berlin and so phoned the Supreme Command, asking the army to withdraw.

Groener refused, stating: '[we] are determined to hold to the plan of liquidation of the Naval Division, and we shall see to it that it is carried out.'

In the early hours of 24 December, as the opposing forces stood eyeballing each other after an extremely tense night, Ebert asked the army to let him through their lines so he could negotiate with the sailors. They refused his request, while the sailors made it clear that they had nothing to discuss.

At 5am the SPD managed to secure the release of Wels and his subordinates. It was hoped that this action would diffuse the tension. The government was mistaken. At 7.30am the sailors in the Schloss were told that they had ten minutes to surrender and, true to their word, the army began operations as soon as the time had expired.

Guns blasted away at the façade of the palace, while Guardsmen dashed into the

building to find it virtually empty. The sailors had fled to the Marstall via an

underground passage.

Guns blasted away at the façade of the palace, while Guardsmen dashed into the

building to find it virtually empty. The sailors had fled to the Marstall via an

underground passage.

This building was now the primary target and after a sharp bombardment, the occupants raised a white flag. The sailors asked for a twenty minute truce in order to arrange their surrender – many of them were wounded and over 30 were dead.

The army made a fatal mistake by agreeing to the truce; within minutes street agitators had gathered thousands of protesters who then rushed into the army positions demanding the assault stop. Surrounded by civilians, the troops held their fire, while the sailors promptly withdrew their white flag. Defeat had been snatched from the jaws of victory and the army commanders ordered a retreat.

News of the fiasco was received with horror by the Supreme Command and the SPD, while many Spartacists, particularly Liebknecht, were now calling for outright revolution. They should strike now, they argued, before the elections (to be held in January) gave Ebert a democratic mandate.

Rosa Luxemburg urged caution, but was ignored and in celebration and in preparation for the forthcoming takeover of power, they re-named themselves the German Communist Party – the KPD.

Lull Before The Storm

Desperate, Ebert phoned Groener asking what he could do. The general replied

that the Chancellor should immediately recall Noske and make him defence

minister. Ebert took the advice.

Desperate, Ebert phoned Groener asking what he could do. The general replied

that the Chancellor should immediately recall Noske and make him defence

minister. Ebert took the advice.

In the meantime, Liebknecht, far from organising a plan to take power, busied himself putting together a special edition of the extreme-left newspaper, Rote Fahne, denouncing Ebert's government.

The sailors were content to rest on their laurels, while the USPD inadvertently helped Ebert's cause by withdrawing from his government, believing that they could only keep their support base by being in opposition. It was a poor political move, and one that gave the Chancellor further control over the apparatus of the state.

Noske arrived in Berlin bristling with confidence a few days later. His job would be a tough, dirty and dangerous, but he was ready: 'Someone must become the bloodhound,' he said.

Noske and Ebert began a high-stakes strategy of moving against their opponents – starting with the troublesome Eichhorn. They demanded he step down as police chief, but Eichhorn refused, confident that the government had no means of forcing him to go.

He had also been in talks with Liebknecht and his colleague Wilhelm Pieck (the future president of Communist East Germany), and had gained the Spartacist's support. Together with the militant trade unions, they called for a general strike to begin on 5 January – it was to be the start of the showdown with Ebert's government. They had no idea, however, that the SPD now had a secret and ruthless force at their disposal – the Freikorps.

A New Force

The Freikorps appeared, even to those in power, to have come out of nowhere. In

fact, their seeds were sown as the Imperial Army was collapsing when the Supreme

Command decided to allow the formation of elite volunteer units.

The Freikorps appeared, even to those in power, to have come out of nowhere. In

fact, their seeds were sown as the Imperial Army was collapsing when the Supreme

Command decided to allow the formation of elite volunteer units.

The men were hand picked for their reliability – a good number had been Stormtroopers on the Western Front. Arms and equipment were readily available, for Germany at that stage was awash with unused weaponry.

The first Freikorps was created by General Ludwig von Maercker. His men were well paid, well motivated and they loathed, above all others, the far-left. Maercker had also chosen some excellent staff to help develop new urban warfare tactics.

Other Freikorps were being formed too. In rebellious Kiel, for example, several brigades had been created, including the 1,600-men 'Iron Brigade', set up under Noske's auspices after he had quashed the mutiny. In January 1919, however, there were still not that many units – they numbered no more than a dozen – although more were being founded, seemingly with each passing day.

On 4 January, as the Spartacists plotted, Noske invited Ebert to a military camp

35 miles south-west of the capital to inspect the results of Maercker's work. Standing in the grim cold, they were presented with the somewhat surreal sight

of 4,000 men marching across the parade ground in perfectly ordered ranks.

On 4 January, as the Spartacists plotted, Noske invited Ebert to a military camp

35 miles south-west of the capital to inspect the results of Maercker's work. Standing in the grim cold, they were presented with the somewhat surreal sight

of 4,000 men marching across the parade ground in perfectly ordered ranks.

Noske and Ebert could hardly contain their glee as the soldiers stamped past. The defence minister gave the Chancellor a slap on the back, saying: 'Now you can rest easy; everything is going to be all right from now on.'

Sunday January 5 saw a gigantic protest march in favour of Eichhorn. As the crowds gathered, revolutionary groups seized the major railway stations and communications centres. That evening leaflets were printed calling for more massed demonstrations for the next day.

The Marstall sailors were invited to join the rising, but they remained non-committal, unwilling to risk the position they had only just managed to hold. The following day, the crowds gathered again – all expecting that a full-scale revolution was about to be declared – but nothing happened. The 'Revolutionary Committee', a 53-man group headed by Liebknecht debated, hummed, hawed and came up with no decisive measures. It was this dallying that gave the SPD their lifeline.

No Quarter

By 7 January the lead elements of the Freikorps had gathered in leafy West

Berlin under the guidance of Noske. About 900 other men were stationed at the

north Berlin barracks of Moabit under the command of Colonel Wilhelm Reinhard.

By 7 January the lead elements of the Freikorps had gathered in leafy West

Berlin under the guidance of Noske. About 900 other men were stationed at the

north Berlin barracks of Moabit under the command of Colonel Wilhelm Reinhard.

Another Freikorps, the 'Potsdam Regiment', had also mobilised and numbered around 1,200 men. They were under the immediate command of Major von Stephani and on the night of January 9-10 were ordered into Berlin to prepare for operations.

Once the order had come through, Stephani decided to head out in advance and make his own reconnaissance. He raced over to the offices of the SPD newspaper Vorwärts that had been taken over by the Spartacists and, disguised as a revolutionary, made a detailed investigation of the building.

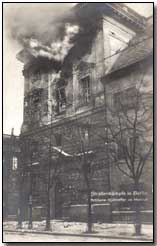

Stephani was confident of success and upon returning to his forces, issued a demand for the Spartacists to surrender. Predictably, they refused and at 8.15am on 11 January, Freikorps machine guns, howitzers and trench mortars blasted the Vorwärts building. The Spartacists tried to reply with their own machine guns, but once registered, were promptly obliterated by the Freikorps' overwhelming firepower.

Having faced several minutes of ferocious assault, seven Spartacists left the building waving white handkerchiefs and offered to discuss details of a possible truce – the Freikorps demanded unconditional surrender instead.

One of the Spartacists was sent back to tell his comrades, while the other six were taken away and executed. Then, not bothering to wait for a reply (there was to be no repeat of the Marstall fiasco), Stephani's shock-troops ran forward and stormed the building, capturing around 300 prisoners - many were beaten senseless and again, some were shot out of hand.

On January 11, Gustav Noske and of his forces in West Berlin moved out, with the defence minister walking at the head of a large column made up of men predominately from the bulk of Maercker's Volunteer Rifles and his Iron Brigade (who had rushed to Berlin to join in with operations). After arriving in central Berlin they proceeded to Moabit barracks, where they joined Reinhard's forces.

That night a strong detachment of Reinhard's men was ordered to take back the

police headquarters on the Alexanderplatz. They attacked with vigour. Artillery

was brought up and shells screamed into the building, smashing vast chunks out

of it. Freikorps infantry followed up the command and stormed into the

headquarters – no quarter was given. Some Spartacists did, however, escape over

the rooftops.

That night a strong detachment of Reinhard's men was ordered to take back the

police headquarters on the Alexanderplatz. They attacked with vigour. Artillery

was brought up and shells screamed into the building, smashing vast chunks out

of it. Freikorps infantry followed up the command and stormed into the

headquarters – no quarter was given. Some Spartacists did, however, escape over

the rooftops.

On January 12 Noske spent the day consolidating his positions. Within 24 hours he was ready to unleash his army. Freikorps men, working in small teams, closed off blocks of Berlin at a time. Civilians were under curfew and any protest gathering was broken up – by force if necessary. At night searchlights were set up and anyone caught in their glare was deemed to be a 'legitimate' target. Within days the general strike was called off and by midnight January 15 the Spartacist revolution collapsed.

Double Murder

The leadership of the uprising was now being hunted down. The two major prizes,

of course, were Liebknecht and Luxemburg. Liebknecht had initially escaped to a

safe house in the working class district, but on January 14, fearing the

authorities were on to him, he had fled to a cousin's house in the middle class

district of Wilmersdorf.

The leadership of the uprising was now being hunted down. The two major prizes,

of course, were Liebknecht and Luxemburg. Liebknecht had initially escaped to a

safe house in the working class district, but on January 14, fearing the

authorities were on to him, he had fled to a cousin's house in the middle class

district of Wilmersdorf.

He erroneously thought that nobody would think of searching for him in the midst of the bourgeoisie. Wilhelm Pieck and Rosa Luxemburg joined him shortly afterwards.

On 15 January Liebknecht and Luxemburg wrote their last articles for the Rote Fahne. Liebknecht's parting shot proclaimed: 'our programme will live on: it will dominate the world of liberated humanity.'

At 9pm that evening, a patrol from a Freikorps unit stationed nearby broke into the apartment, having been tipped off by a local resident. The soldiers seized the communist leaders and took them to the Eden Hotel for 'questioning'. Wilhelm Pieck seems to have cut a deal to stay alive, for they eventually released him. As for Liebknecht and Luxemburg, the Freikorps had other plans for them...

Liebknecht's body was dumped at the morgue near to the zoo and Luxemburg's was

thrown into the Landwehr canal. It would be found five months later, barely

recognisable. The Freikorps celebrated the crushing of their enemy, and were so

sure of their position, and so contemptuous of their opponents, that they only

bothered to construct half-hearted alibis.

Liebknecht's body was dumped at the morgue near to the zoo and Luxemburg's was

thrown into the Landwehr canal. It would be found five months later, barely

recognisable. The Freikorps celebrated the crushing of their enemy, and were so

sure of their position, and so contemptuous of their opponents, that they only

bothered to construct half-hearted alibis.

Ebert knew that the Freikorps had executed the two revolutionaries in cold blood and so ordered an investigation. But the Freikorps were not about to let 'heroes' be sent to prison – and the judiciary agreed. In a risible trial, only two of the men, Lieutenant Vogel (the man who probably fired the fatal shot into Rosa Luxemburg), and Otto Runge, were given sentences – two years each.

Vogel was promptly helped to escape captivity by Naval Lieutenant Wilhelm Canaris, and then driven to safety of the Dutch border. Canaris would later command the Nazi Abwehr and German Military Intelligence.

Showdown

Having survived the uprising, the government called the promised elections. They

were held on 19 January and the SPD came first with an overwhelming 40% of the

vote. But as the new Assembly gathered in the town of Weimar, unemployment and

starvation were beginning to seriously destabilise the nation.

Having survived the uprising, the government called the promised elections. They

were held on 19 January and the SPD came first with an overwhelming 40% of the

vote. But as the new Assembly gathered in the town of Weimar, unemployment and

starvation were beginning to seriously destabilise the nation.

Reacting to the discontent, Communist uprisings flared up across the country. Unfortunately, for the USPD, KPD and their allies, no single supreme command for co-ordinating a revolution existed. The government was able to move Freikorps units to each flashpoint and use them to crush each insurgency one at a time.

By March, all eyes were turned again to Berlin. Having re-grouped the Spartacists tried to seize control for a second time. On the morning of 3 March the Rote Fahne proclaimed a general strike.

Noske immediately declared a state of siege in the city and gave the order for the Freikorps to enter Berlin on 4 March. That afternoon, crowds gathered outside the police headquarters on Alexanderplatz and, having roughly handled a Freikorps detachment, promptly found themselves on the receiving end of armoured car machine guns.

On the next day the People's Naval Division received news that they had been 'disbanded' after the government issued an official announcement of the fact. Disgruntled, a group of sailors approached the Berlin Police HQ to voice their protest. Jumpy from the previous day, one of the Freikorps soldiers shot and mortally wounded a sailor. Enraged and wanting revenge, the People's Naval Division threw their lot in with the revolutionaries. That night angry mobs, including sailors, surrounded the police station and were only kept at bay by sustained rifle fire.

March 6 saw the climax to the fighting. Colonel Reinhard arrived near the Alexanderplatz with his Freikorps and even a tank. The infantry split into small

groups and began to slash a path through the revolutionaries, rapidly taking

over their key strong-points.

March 6 saw the climax to the fighting. Colonel Reinhard arrived near the Alexanderplatz with his Freikorps and even a tank. The infantry split into small

groups and began to slash a path through the revolutionaries, rapidly taking

over their key strong-points.

During the battle, they had come under fire from the Marstall. Furious, the Freikorps turned their heaviest guns on the building. Within half an hour the former Imperial stables were theirs and the army's Christmas humiliation was avenged.

However, the defenders in a neighbouring building named the 'People's Marine House' offered stiffer resistance. To help crush these revolutionaries an air strike was called in – yet the sailors continued fight on. Reinhard ordered an outright assault, but it took three attacking waves before victory was secured.

The Spartacists and their allies were then slowly beaten back to working-class tenements of East Berlin. Here they threw up barricades and turned the entire suburb of Lichtenberg into an armed fortress. An estimated 10,000 revolutionaries prepared for the final showdown.

Blood On The Streets

On 9 March a rumour circulated that the Lichtenberg police station had been stormed by revolutionaries and that 70 police officers had been executed in cold blood.

The Vorwärts, like many other publications, reported the next day that the men had been: 'shot like animals'. The story was an exaggeration. Five policemen had been killed, although the exact cause for why still remained unknown. Regardless of the facts, however, Noske now issued his notorious order declaring: 'Any individual bearing arms against government troops will be summarily shot.'

For the next four days the Freikorps ripped into East Berlin. Thirty sailors from the People's Naval Division were gunned down in a courtyard for having the audacity to turn up to a government office demanding back pay. In one case a father and a son were dragged into the street and shot. T heir crime: possessing the handle of a stick grenade.

By 12 March, the Freikorps burst into the building housing the Workers' Council of Berlin, the Spartacist nerve centre. The Council was forcibly dissolved and peace slowly returned to Berlin's streets. Noske had destroyed the Spartacists and seen the sailors crushed, yet the price had been high: between 1,200 and 1,500 were dead and roughly 12,000 wounded, although with negligible losses to the Freikorps.

Many of those involved in smashing the Berlin uprisings sincerely believed that

that they were saving lives in the long run by stopping Germany from descending

into a Red Terror as experienced by millions in Lenin's Russia.

Many of those involved in smashing the Berlin uprisings sincerely believed that

that they were saving lives in the long run by stopping Germany from descending

into a Red Terror as experienced by millions in Lenin's Russia.

In this their fears were well grounded. Liebknecht certainly had no bones about calling for the blood of his enemies, and the Spartacists and the People's Naval Division had a propensity for using fighting methods equally as brutal as those favoured by the Freikorps.

But regardless of the threat Germany faced, it is difficult to excuse much of the suffering the Freikorps inflicted on Berliners, particularly in March 1919. The freehand given to them in the capital, the lessons they had learnt there, and the official recognition they subsequently received would critically weaken the new Weimar Republic.

In the long run, many would turn against Ebert, the German people and eventually, the rest of the world, when a large proportion of Freikorps veterans found their way into influential positions within the administration of the Third Reich and its terror organisations.

Select Bibliography

Compiled by Langewiesche-Brandt,

Anschläge 220 politische Plakate als Dokumente der deutschen Geschichte 1900-1980, Langewiesche-Brandt,

1983

Compiled by Langewiesche-Brandt,

Anschläge 220 politische Plakate als Dokumente der deutschen Geschichte 1900-1980, Langewiesche-Brandt,

1983

Bullock A, Hitler: A Study In tyranny, Penguin, 1990

Gill, Anton, A Dance Between Flames, New York, Carol and Graf, 1993

Jones N, The Birth Of The Nazis – How The Freikorps Blazed A Trail For Hitler, Robinson, London, 2004

Junger E, Storm Of Steel, Penguin, 2003

Jurado C C, The German Freikorps 1918–23, Elite, Osprey, 2001

Large D C, Where Ghosts Walked, W W Norton & Company, 1997

Lee S J, The Weimar Republic, Routledge, 2003

Lewis J E (edited by), The Mammoth Book Of How It Happened: World War I, Robinson, 2003

Watt R M, The King’s Depart, Phoenix, 2003

Willmott H P, First World War, Dorling Kindersley, 2003

Website: www.firstworldwar.com

Contributed by Simon Rees

An earlier edition of this article appeared in Military Illustrated

"Bellied" was a term used to describe when a tank's underside was caught upon an obstacle such that its tracks were unable to grip the earth.

- Did you know?