Primary Documents - Paul von Hindenburg on Kaiser Wilhelm II's Abdication, 20 March 1919

With Germany actively

seeking an armistice and revolution threatening, calls for

Kaiser

Wilhelm II to abdicate grew in intensity. Wilhelm was

himself deeply reluctant to make such a sacrifice, instead expressing a

preference to lead his armies back into Germany from the Western Front.

Upon being informed by his military advisers that the army could not be

relied upon not to harm him

Wilhelm abandoned the notion.

With Germany actively

seeking an armistice and revolution threatening, calls for

Kaiser

Wilhelm II to abdicate grew in intensity. Wilhelm was

himself deeply reluctant to make such a sacrifice, instead expressing a

preference to lead his armies back into Germany from the Western Front.

Upon being informed by his military advisers that the army could not be

relied upon not to harm him

Wilhelm abandoned the notion.

Wilhelm's abdication was announced by Chancellor Prince Max von Baden in a 9 November 1918 proclamation - before Wilhelm had in fact consented to abdicate (but after Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann had announced the Kaiser's departure from the balcony of the Reichstag). Faced with a fait accompli Wilhelm formally abdicated and went into exile in Holland. His abdication proclamation was formally published in Berlin on 30 November 1918.

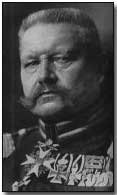

Faced with public criticism over the nature of Wilhelm's abdication German Army Chief of Staff Paul von Hindenburg issued a statement on 20 March 1919 explaining the sequence of events and defending the Kaiser's role (reproduced below).

In the wake of the Kaiser's abdication his eldest son - Crown Prince Wilhelm - expressed a desire on 11 November 1918 - the date of the armistice - to be allowed to lead his army back home to Germany. His wish was, given the anti-royalist fervour of the moment, rejected out of hand by the government. He too went into exile in Holland, despatching a letter to Hindenburg following his arrival in which he explained and justified his position.

Having instigated the Kaiser's abdication Prince Max resigned, handing power to incoming Chancellor Friedrich Ebert who, in statements issued on 10 November and 17 November, appealed for public calm and reassured the German public that the incoming government would be "a government of the people".

Paul von Hindenburg on Kaiser Wilhelm II's Abdication, 20 March 1919

Public opinion has been recently discussing the question why the Kaiser went to Holland. To obviate erroneous judgments, I should like to make the following brief observations.

When the Imperial Chancellor, Prince Max of Baden, announced the Kaiser's abdication on November 9th, without the Kaiser's previous declaration of assent, the German Army was not beaten, but its strength had dwindled and the enemy had fresh masses in readiness for a new attack.

The conclusion of the armistice was directly impending. At this moment of the highest military tension revolution broke out in Germany, the insurgents seized the Rhine bridges, important arsenals, and traffic centres in the rear of the army, thereby endangering the supply of ammunition and provisions, while the supplies in the hands of the troops were only enough to last for a few days.

The troops on the lines of communication and the reserves disbanded themselves, and unfavourable reports arrived concerning the reliability of the field army proper.

In view of this state of affairs the peaceful return home of the Kaiser was no longer to be thought of and could only have been enforced at the head of loyal troops. In that case the complete collapse of Germany was inevitable, and civil war would have been added to the fighting with the enemy without, who would doubtless have pressed on with all his energy.

The Kaiser could, moreover, have betaken himself to the fighting troops, in order to seek death at their head in a last attack; but the armistice, so keenly desired by the people, would thereby have been postponed, and the lives of many soldiers uselessly sacrificed.

Finally, the Kaiser might leave the country. He chose this course in agreement with his advisers, after an extremely severe mental struggle, and solely in the hope that he could thereby best serve the Fatherland, save Germany further losses, distress, and misery, and restore to her peace and order.

It was not the Kaiser's fault that he was of this opinion.

Source: Source Records of the Great War, Vol. VI, ed. Charles F. Horne, National Alumni 1923

One in five of the Australians and New Zealanders who left their country to fight in the war never returned; 80,000 in total.

- Did you know?