Primary Documents - Official German Account of the Battle of the Somme, 1 July 1916

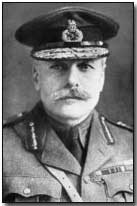

1st July 1916 saw the onset of

the predominantly British-led

Somme Offensive. Planned as a means of

relieving German pressure upon the French at

Verdun, and viewed by British

Commander-in-Chief Sir Douglas Haig as a means of achieving a breakthrough on

the Western Front, the offensive opened with significant British casualties,

some 60,000 on the first day alone. The British had mistakenly expected German

resistance to be crushed following a week-long preliminary bombardment of the

German lines but instead found machine-gunners awaiting their infantry advance.

1st July 1916 saw the onset of

the predominantly British-led

Somme Offensive. Planned as a means of

relieving German pressure upon the French at

Verdun, and viewed by British

Commander-in-Chief Sir Douglas Haig as a means of achieving a breakthrough on

the Western Front, the offensive opened with significant British casualties,

some 60,000 on the first day alone. The British had mistakenly expected German

resistance to be crushed following a week-long preliminary bombardment of the

German lines but instead found machine-gunners awaiting their infantry advance.

The Somme Offensive did not provide the much sought after breakthrough but largely resulted in continued trench stalemate, although some territorial gain was achieved by Allied forces. Casualty estimates vary widely: the Allied losses (chiefly British and French) have been put at 600,000 with German casualties estimated to be 500,000.

Reproduced below is the official Germany account of the offensive written by General von Steinacker.

Click here to read Sir Douglas Haig's Somme despatch. Click here to read a summary of the opening of the offensive by one of Britain's official war reporters, Philip Gibbs. Click here to read the summary written by German commander Crown Prince Rupprecht. Click here to read the official Germany account of the offensive written by General von Steinacker.

Click here to read Alfred Dambitsch's Somme memoirs; click here to read Alfred Ball's memoirs.

The Battle of the Somme by Official German Historian General von Steinacker

The failure of the English-French attempts to break through in Champagne and Artois in the fall of 1915 - an offensive planned upon a large scale - did not dishearten the enemy.

Immediately on the termination of these battles - exceptionally costly in human lives - the preparations began anew. The English command was particularly active and displayed the utmost celerity in getting the new armies ready for the field.

Simultaneously the accumulation of war material of every description went on apace, in order that the enemy might be outstripped in this regard. The new offensive was planned for June. Although the drilling of the Englishmen had not been quite completed, the condition brought about at the beginning of the year by the attacks of the Germans on the positions at Verdun made it imperative for Sir Douglas Haig and General Joffre to choose the above period as the latest feasible one.

The attack launched on July 1 was regarded by the German high command as one fraught with great significance as determining the outcome on the Western front. They believed, indeed, that it was designed to bring about a decisive change, not only on the Western front, but also on every other scene of action, by which the Central Powers would be irrevocably forced to assume the defensive.

This end was to be achieved by piercing the Western front, which thereupon would crumble throughout its entire length and breadth. The intention of the enemy was correctly deduced from the magnitude of the preparations made.

Above all, however, it is necessary to point to the fact that both Frenchmen and Englishmen had stationed tremendous masses of cavalry behind the battlefront, designed, after a successful penetration of the German lines, to fall into the rear of the enemy, annihilating such bodies as had not been directly affected in the first onset.

The British command, deviating from the statement, but only after the conflict had terminated, gave out the following as the reasons for the battle: (1) Relieving the pressure on Verdun; (2) preventing further levies of troops from the Western to the Eastern front; (3) attrition of the German forces.

The front which the enemy had selected as his point of attack, extended in an airline over about 40 km. It lay in Picardy, between the villages of Sommecourt and Vermandovillers. This territory easily resolves itself into three divisions, the northern of these being Sommecourt-Hamel, the central Thiepval-Curlu, and the southern Frise-Vermandovillers.

The position of our army had been admirably strengthened since its occupation a year and a half before. Many villages lay along the first line and these villages, generally built of stone and containing cellars, served as valuable points d'appui.

Though the second line also passed through as many as ten villages, the first line was the stronger of the two, and here the greatest resistance was to be made. For this reason the second position had from one to two lines only protected by extensive wire defences. It was so situated that it could not be affected by the fire directed against the first position.

Although the enemy spared no effort to conceal his purpose, his in every respect well considered preparations did not escape the observation of Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, who was here in command.

On June 22nd the enemy prepared his attack by especially vigorous artillery fire. By June 30th all the German positions had already suffered greatly by reason of the increasingly vigorous and effective drumfire.

The battle, which began on July 1st with infantry charges, lasted in all four and a half months; that is, until November 18th. It may chronologically be divided into several parts.

The first comprised the period July 1st-5th. T he attack was begun by one and a half French corps under General Michelet, advancing south of the Somme; by one corps north of the river commanded by General Fayolle; at Maricourt and in touch with the French stood the right wing of the English, the fourth army (consisting of five corps) here moving forward to the attack under General Rawlinson.

While on July 1st the first German line was taken south of the Somme by the French, who also advanced north of that river as far as Hardecourt-Curlu, the attack of the English on both sides of the Ancre did not go forward very well.

Already by July 2nd the combined attack of the enemy forces resolved itself into single engagements, which resulted more favourably for the French south of the Somme. After uninterrupted attacks lasting five days, a pause ensued.

According to the enemy's own reports, new grouping and relief troops had become necessary, and the heavy artillery had to be brought up.

The second period, July 7th-19th, presented a varying picture, but resulted in important advantages to the attacker.

The third period, July 10th-31st, was a fierce struggle intensified by the entry into the fight of German reserves, especially of the artillery division. The great united forward movement of the English-French army, consisting of seventeen divisions with 200,000 men, continued to the 30th, the day of the hottest fighting.

The only result of these conflicts was the seizure of the ruins of the village of Pozieres by the English.

The further development of the battle; that is, during the fourth period, which included the month of August, was characterized by varying attacks along the entire front and by efforts to gain important points of vantage and points d'appui, such as villages or strips of forest, the initiative being with the enemy. Here and there a slight advance was made.

On September 3rd began the fifth period of this battle, characterized by an attack north of the Somme, to be followed on the next day by one south of it. Yet, although conceived as a unity, this general attack, owing to the conditions of the ground and the direction of the advances, resulted in two distinct operations.

First, as to the movement north of the Somme. Whereas the right wing, that is, the French, made a considerable advance; the left wing, that is, the English, made no headway. On the 23rd the artillery ushered in another combined attack, the infantry charges of the French resulting in their advance northwardly to the stretch Bouchavesnes-Combles, the latter city being evacuated.

The English advanced to Thiepval, and at the end of the month stood before Le Sars and Eaucourt l'Abbaye. To the south of the Somme the attack, made in a southeasterly direction on a front of 20 km., also resulted in the capture of strategical points.

In spite of all the efforts of the Germans it appeared as if the enemy in those days would succeed in his object. The measures taken for defence could not keep pace with the force of the attacks launched by the enemy.

Only on September 25th had it become possible to so strengthen and increase the artillery support of the German positions that a systematic and effectual opposition to the enemy's forces might be organized - as the General German Headquarters put it, "A harmonious cooperation of the artillery of all divisions toward the suppression of any desire for attack on the part of the enemy."

Consequently the conflicts of October, which constituted the sixth period in the series of battles, presented an essentially different picture from those of the preceding months. True, the enemy attacks did not immediately diminish in vigour. On the 1st and 2nd of October, as on the 7th, the attacker succeeded in advancing, Eaucourt-l'Abbaye and Le Sars falling into his hands.

Nevertheless, the result of the English-French attacks from October 9th to the 15th, which were directed under unified command against the whole German front from Courcelette southeasterly to Bouchavesnes and which belonged to the most important combats fought here, demonstrated that their goal would not be attained.

The German Tenth Army successfully repelled the attack made on the 12th, the day of the hottest fighting. The day of the last great battle, October 18th, resulted in gaining for the Allies a little ground near Sailly and north of Eaucourt-l'Abbaye.

After another great combined attack on the 21st had been shattered with sanguinary results, the struggle gradually diminished in vigour.

The great Battle of the Somme was ended without bringing about a decision. The result was limited to a "bulging in" of the German position, so to speak, a result achieved at a cost of approximately three quarters of a million lives. The losses of the defender were well below half a million, which is the more remarkable in view of the fact that, according to official reports, about 76 per cent of all the wounded were able within a relatively short time to return to the front in fighting condition.

A utilization of the successful defence made was impossible for the German command owing to the relative strength of the two armies. There was no decision reached on this theatre of war. The failure of the attempt to break through resulted in a change in the French high command, General Joffre being replaced by General Nivelle, the commander of the Army of Verdun.

Source: Source Records of the Great War, Vol. IV, ed. Charles F. Horne, National Alumni 1923

An "incendiary shell" is an artillery shell packed with highly flammable material, such as magnesium and phosphorous, intended to start and spread fire when detonated.

- Did you know?